Indeed, the anti-trans and anti-homeless propaganda cited above can and should be defined as a form of genocidal discourse, namely “a widely used and accepted language of negation, destruction and erasure targeted at a particular group or groups” (Townsend 2014 : 9). Trans and homeless people are not merely depicted pejoratively, their very existence is widely considered to be a “nuisance” that ought to be gotten rid of. Political actors spread this form of propaganda in order to build up popular adhesion to a specifically genocidal – that is, eliminationist – version of what political scientist Jonathan L. Maynard calls “atrocity-justifying ideologies”:

Atrocity-justifying ideologies label victims as dangerous threats or guilty criminals, assert that society is at a crisis-filled turning point, euphemistically reframe killing as “self-defence” or “serving the revolution,” and enrich all of these claims with textured historical narratives and mythical “knowledge.” It is often these sorts of ideological elements which make violence look desirable, or at least permissible, to many ordinary perpetrators.

(Jonathan Leader Maynard 2014: 825)

Paraphrasing Maynard, Williams and Neilsen write that:

ideologies serve to motivate, legitimate, and rationalise killing for policy-initiators, perpetrators, and bystanders. To motivate means to provide the impulse for action, to legitimate means to make the act permissible, and to rationalise means to grapple with the act retrospectively, while putting it in a positive light.

(Timothy Williams & Rhiannon Neilsen 2016: 6)

Understanding the specific role and functions of genocidal propaganda and ideology is complicated because causation and determination in politics, history and human society are always very complex, nonlinear, contradictory and multifaceted (which is why it’s almost impossible to fully 100% “prove”/ any general/mechanical/positivist causal hypothesis in social science, contrary to rigid positivist ideals; that doesn’t mean solid analysis and theoretical explanations can’t be done, but the unavoidable indetermination and multi-determination of the social has to be accounted for carefully). As Aliza Luft highlights in this important summary of the contemporary research and issues in understanding the relationship between dehumanization (propaganda and ideology) and the normalization/motivation/production of violence,

While it is true that genocidal governments—and other governments bent on normalizing state violence (e.g., the United States during slavery)—promote images of unwanted populations as animals and objects, such actions tell us little about how they are received by civilians.

Research on atrocity-committing regimes/contexts/movements such as the Nazis’ Third Reich and the Holocaust, the most brutal periods of Stalinism and Chinese Maoism, the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, the 1994 genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda, or the “Yugoslav” wars and the Bosnian genocide, have shown how contrary to the intuitive (and understandable/plausible) assumption/idea that it is primarily dehumanization through ideology and propaganda that motivates large-scale atrocities – that is, that it is what makes a large amount of people actively participate in them and commit violence -, their role is far more ambiguous, differentiated and mediated by various things/factors. This is actually an epistemological and conceptual problem across a lot of sociopolitical discussions and even formal research: the bourgeois idealist and rationalist assumption that what drives individuals to act and behave in specific ways is primarily coherent, logically formulated/developed ideologies, and “rational” and informed choices/decisions/considerations (meaning that in order to do something that might seem “irrational”, you’d first need need to be convinced through “rational” arguments and thinking). Luft continues:

In sum, whether in Germany during the Holocaust or Rwanda during the genocide, we still lack clear evidence that dehumanizing propaganda convinced ordinary civilians to change their minds about their neighbors and kill them. Moreover, even in cases where a possible link between broadcast data and participation can be established (…) it is still unclear what mechanism links dehumanizing propaganda to killing. For example, MacArthur Fellow Betsy Levy Paluck developed an experiment in postgenocide Rwanda where some people heard a radio soap opera about an interethnic relationship where the couple started a peaceful revolution against leaders who sought to sow hate. Others heard a soap opera about health and HIV. She finds that although people didn’t agree with the messages of the former, they were aware of its pro-reconciliation themes and thought others believed it and so they changed their behaviors even if their beliefs stayed the same. It is possible that during genocides a similar mechanism is at work as well. That is, dehumanizing propaganda sends signals to people about what they think others believe and, even if they disagree, those perceptions can alter their actions in turn.

The “microlevel turn” in genocide rsearch since the late 1990s (Luft cites Browning 1992, Finkel & Straus 2012, Fujii 2009, Hinton 2004, Luft 2015, McBride 2016, and Straus 2006), has contributed greatly to the research on why people participate in genocide:

[This approach] focuses on variation in individuals’ motivations and behaviors, and emphasizes that, in any conflict, multiple mechanisms may be at play, motivations can change over time, and the same individual can vary their behaviors from killing to not killing and even saving during a genocide. It is therefore impossible to attribute any one motivation to why people kill, let alone to why the same individual kills over time, during a genocide. That said, important patterns are emerging in identifying the many mechanisms that draw ordinary people into, or away from, genocidal violence.

We therefore know that individuals’ decisions to kill are strongly influenced (obviously in a differentiated way for different groups and contexts):

1. In-group norms and peer pressure

2. Face-to-face mobilization/solicitation, e.g. “individuals, leaders, or groups directly solicited…at commercial centers, on roads and pathways, or at their homes” (Straus 2006)

3. Obedience to authority, hierarchical pressures and the fear of retributions/coercion if resisting/refusing to take part* (for instance there is evidence of this concerning the Holocaust, the 1994 Tutsi genocide, and the Cambodian genocide by the Khmer Rouge)

4. Inequality channelling participation through greed and grievance (this is a form of politicization, as I defined here);

5. *Socioeconomic inequality and class relations also potentially making it impossible for certain individuals and groups to resist leaders/extremists’ coercion/mobilization

These findings don’t imply that dehumanization via ideology/discourse/propaganda/etc don’t matter, rather they call for more precision in understanding how they do matter, and how it is articulated with and conditioned/mediated by other dynamics/dimensions. This brings us back to Maynard:

Ideology cannot (…) be presumed to be relevant at only one part of the machinery of atrocity-perpetration. In terms of their causal relationship to violence, a loose distinction can be drawn between three main categories of perpetrators: policy-initiators (who make the key decisions which lead to the commission of atrocities); direct killers (who do not issue the original orders to kill, but carry out the acts of physical destruction); and bystanders (who do not actively participate in killing, but possess potential unused power to frustrate it, making their passivity a key enabling condition). These categories are not completely clear cut: sometimes policy-initiators may serve as direct killers as well, and in relatively spontaneous acts of atrocity there may be no discretely identifiable policy-initiators. We might also want to talk about two further categories: indirect killers (staffing the bureaucracies linking policy-initiators and direct killers) and victims (given the ways they have occasionally been tragically complicit in their own destruction, most famously in the case of the Jewish Sonderkommando in the Holocaust).

A successful account of the ideological dynamics of atrocities should explore the potential role of ideology for all these participant categories, and should avoid the temptation to treat them as homogenous blocks, with members all sharing the same motives and mind-sets. As many theorists emphasise, perpetrators of violence participate for a variety of reasons and in a range of dispositional states. As such, they maybe influenced by ideological beliefs held with varying levels of commitment, conviction, and consciousness. In general (…) we might expect atrocity-justifying ideologies to be endorsed with greater conviction amongst policy-initiators than direct or indirect killers. We might also expect ideology to play a more active motivational role for the former, and a more passive enabling role for the latter. And at least in the cases of the Nazi and Stalinist leaderships, data on the internal discourse of the regime can be found which supports such a presumption. But these are still broad-brushed generalisations. Actual assessments of ideology’s role should be attuned to complex distributions of ideological belief across members of participant categories, rather than reaching binary conclusions to the effect that some groups of killers “are ideological” whilst others “aren’t.”

(Jonathan Leader Maynard 2014: 826)

For example, here’s Williams and Neilsen’s conclusion in the case of the Khmer Rouge:

We found that [the idea of] toxification, as [something/someone being] toxic to the ideal, was rife in Khmer Rouge propaganda and discourse. The governing regime used toxification to portray the mass killing of minorities as an acceptable, necessary, and laudable pursuit. Yet, in interviews conducted with former cadres of the Khmer Rouge, few individuals reported such an atrocity-justifying ideology as the motivating factor for such violence. Instead, interviewees recalled toxification ideology and referred to this when discussing the legitimacy of the killings and how enemies were constructed. Thus, toxification seems to have served more the purpose of moral justification and as a rationale for genocide, rather than functioning as the actual motivation to kill.

(Timothy Williams & Rhiannon Neilsen 2016: 15)

A notorious example of the role of the media in genocide is the 1994 genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda. In her book Kill the Messenger: The Media’s Role in the Fate of the World, here’s how Maria Armoudian describes what the anti-Tutsi media – including the infamous Radio-Télévision Libre des Milles Collines (RTLM) – did and their impact:

In just over three months, the Hutu people had brutally exterminated three-quarters of Rwanda’s Tutsi population as well as Hutus who resembled the Tutsis, had helped a Tutsi escape, or had refused to kill. But most violators were ordinary people who had not committed violence in the past, and many were remorseless in the killings, believing that they were doing an important job by avenging the death of their president, defending themselves from what they believed was an oncoming slaughter or exterminating the “cockroaches” that were causing all their political and economic troubles. And although there had been periods of ethnic rivalries among extremists, most Tutsis and Hutus had lived side by side, intermarried, and attended the same schools and churches. And historically, they had banded together to fight common enemies. Differences between them were minimal.

(…) Broadcasters portrayed the genocide as a grand cause, for which all walks of life, including children, teenagers, and the elderly, were recruited. That grand cause, according to these journalists, was the permanent eradication of evil. Like Hitler’s “final solution,” this “final war” required them to “exterminate the Tutsi from the globe . . . make them disappear once and for all.” The cause contained four “righteous” ends: righting injustice through revenge and destruction, asserting self-defense, instilling a majoritarian democracy, and protecting their country. With this crusade, Hutus could feel that the savage deeds before them were a means to a good end.

(…) In addition to provoking destructive emotions, Hutu Power journalists helped organize massacres by broadcasting the Tutsis’ hiding places and directing searches. They called upon listeners to scrutinize abandoned houses, and in drains, ditches, water conduits, and gutters, “especially in the evening,” when people in hiding might scrounge for food.

(…) Through “blame frames” and “hate frames,” the media incited ethnically based resentment, fear, anger, pride and hatred – intense emotions in a combination that had not been widespread. The emotions and new cultural values guided behavior. Hutus’ growing fear, resentment, anger, and hatred emerged from the belief that their neighboring Tutsis were evil, were plotting genocide, and must be preemptively exterminated. As greater numbers of community members joined the cause, it became increasingly difficult to resist the ubiquitous forces of culture and intergroup emotions. “We had lived with Tutsi friends,” explained one of the Hutus who participated in the killing. But soon, “We became contaminated by ethnic racism without noticing it.” Many really came to believe that “the Tutsis would kill us,” they admitted. And “little by little . . . our hearts changed.”

Using the Hutu Power doctrines as their foundation, broadcasters consistently tied annihilation to Rwandans’ values such as patriotism, “work” for their country, and a pathway to honor. Through inundation, repetition, and passion, this juxtaposition aroused emotions, masked the heinousness of the crimes, and transformed the meaning of butchering other human beings into what people believed were lofty, noble acts. “Working” Hutus were bestowed pride and glory, while conscientious objectors were shamed, humiliated, and often killed.

Simultaneously, radio hosts generated an ultimatum of disaster, should the Hutus fail to annihilate the Tutsi people. In their battle of good Hutu versus bad Tutsi, their view was a choice of only two options: either the forces of “death and desolation” or “the people.” As this false dichotomy and the accompanying stories permeated the airwaves, Hutu listeners grew increasingly resentful of the Tutsi people for the litany of injustices they had allegedly perpetrated – particularly the death of their president. “Everyone was angry because the president had been killed,” remarked one of the Hutu killers.

Because only about 50 percent of Rwandans could read, radio’s power was enhanced as a primary means of obtaining political and communal information. Beginning in 1990, most other radio was muted, allowing the Hutu Power’s RTLM to monopolize messaging to the public. Although the RPF broadcast on the AM band’s Radio Mutubara, its broadcasts failed to reach many parts of Rwanda, and the government forbade listening, frequently beating people caught tuning to it. In this radio-oriented society, even some Tutsi people listened to RTLM – largely because of its popular music, entertainment, commentary, and what was believed to be breaking news. Without competing sources of information and framing, and because of their connection to government, these messages were both homogenous and authoritative, ultimately making the Hutu Power’s version of Rwandan politics and the Tutsi people ostensibly more and more plausible.

The media did not convince all listeners. Many Hutus worked alongside Tutsis to prevent intergroup warfare. But the media’s “blame frames” and “hate frames” reinforced the thinking of those who were already inclined toward hardline attitudes and fostered an environment of fear, anger, and hatred. Amid the trying circumstances and virulent messages, within one hundred days, ordinary people who had never before killed rose to collectively slay some eight hundred thousand of their fellow Rwandans. It’s an unbearable chapter of history that unfortunately does not stand alone.

So the question isn’t if the media/propaganda affected this genocide (and genocides or mass atrocities in general), but how:

We may never definitively settle the “media effects” debate – that is, did radio and other media directly incite violence, or were they a secondary driver?

(…) Most early scholarship about the genocide views RTLM as a lethal influence. (…) More recent studies question the primacy of radio broadcasts in directly motivating the killers’ actions. These scholars see radio as an extension of years of state propaganda which was disseminated through schools, churches, and other government institutions.

In a detailed empirical study published in 2007, social scientist Scott Straus found that only 15% of perpetrators cited radio broadcasts as a key influence in their decision to kill Tutsi. Face-to-face intimidation and communication between peers appeared to have a stronger influence. Radio broadcasts were a secondary factor.

[note: Straus’ analysis also points to other important factors/causes not cited by Amand, see p. 630-632]

For another major case study that offers insights on this, Jordan Kiper studied the role of propaganda in the Yugoslav wars (which included the Bosnian and Kosovan genocides as well as other atrocities, forced displacements, and military conflict/border-related violence):

propaganda played a significant role in getting combatants to the frontline and convincing people on the homefront that violence was necessary. Yet, it was an array of sociopolitical conditions brought about by ethnoreligious nationalism and state-sponsored ethnicity – which varied across republics and regions – that most participants remembered as bringing about collective violence. (…) These social conditions allow propaganda to coordinate people who, unlike years before, now see themselves and others, or are treated as if they were, belonging to categorical groups.

…as recalled by most participants across the former Yugoslavia, was a turn toward state-sponsored ethnicity: an ideological frame that nationalist leaders used during the Yugoslav crisis as a reference point for shaping how they, as political elites, could win support and define their political strategies (Fujii 2009, 187; Straus 2015, 57). It drew on pre-crisis narratives about historical legacies of violence, myths of ethnic-national identity, and innovations on religious culture (see also Bringa 1995). As Sell (2003, 309-310) observed, most people did not choose this state-sponsored ethnic identity but discovered that it was imposed on them as succession ensued (see also Gagnon 2004; Lučić 2015). As a political movement, state-sponsored ethnicity—centering on an imagined history but also traumatic collective-memories of WWII (Dragojević 2013; Đurašković 2016), innocence (Živković 2011), and destiny for the people or nation as a unique ethnic, religious, and national community—emerged most memorably in Serbia during the final years of Yugoslavia. Serb nationalists are remembered as exploiting popular crisis-sentiments, ending the civil rhetoric of the Yugoslav era by openly insulting ethnoreligious outgroups, portraying Croatian and Bosnia independence as renewed persecutions of Serbs, and advocating for a land where Serbs could live free from persecution (Oberschall 2012). Serbia under Milošević, in turn, compelled nationalists in neighboring republics to engage in similar demagoguery and use the threat of Serb aggression to promote aggressive political agendas, thus escalating intergroup tensions. Most participants, therefore, remembered state-sponsored ethnicity, first in Serbia but then in Croatia and Bosnia, as engendering a dangerous identity-centered politics that provided the ideology for propaganda and collective violence.

Study results also offer support for propaganda’s secondary influence. Yet, the recalled effects on populations differed in ways overlooked by prior studies. Remarkably, Serb propaganda contributed to outgroup cohesion among many Bosniaks and Croats, convincing former combatants that they had to volunteer for war and that violence against perceived Serb threats was justified. Moreover, Serb participants indicated that the controlled news media under Milošević convinced many that Serbia’s neighboring republics were committing atrocities that Serbs had to prevent if not avenge. Misinformation in Serbia during or after the wars also contributed to present-day denialism about the extent of collective violence among some Serb former combatants. Propaganda also had an indirect influence during the wars by coordinating combatants. The association between propaganda and social pressures to volunteer for combat offer a partial explanation of this effect. While Bosniaks and Croats often experienced social pressures to volunteer for war after their community was exposed to Serb propaganda, many Serb former combatants reported feeling compelled to go to war because of misinformation on Serb-controlled media (Boljević et al. 2011). Alongside state-sponsored ethnicity as a cultural frame, propaganda may have functioned less to instill both hatreds and fears but to coordinate coalitions of would-be fighters (Moncrieff and Lienard 2019). Thus, state-sponsored ethnicity may have provided the necessary cultural ideology and justifications that rendered propaganda as a meaningful signal, around which audiences collected and conveyed their acceptance of violence as a perceived necessity during Yugoslav succession.

Accordingly, these results corroborate several findings from other post-conflict ethnographies. First, granular data challenge the ethnic hatreds and ethnic fears theses and instead support the social interaction thesis: that communities do not support or engage in collective violence because they hated or feared the targeted outgroup but rather because of more immediate, less abstract reasons (Fujii 2009, 185). Here, the most critical factors were similar to other post-conflict ethnographies and included perturbations to economic decline, coercion by peers, legacies of past violence, rumors about neighboring populations, and propaganda. These likely overlapped with other social factors explored by ethnographers in post-conflict Balkan regions such as traditional norms of patriarchy and masculinity (Dumančić and Krolo 2017; Milićević 2006). Second, this study offers evidence that propaganda, as a contributing factor to collective violence, may have both directional and motivational influence that theorists following speech crime trials overlook—for example, Serb former combatants reported feeling compelled to volunteer for war due to propaganda but remember fears and hatreds stemming less from wartime media and more from rumors on the frontline. Third, the triangulation of various data suggest that data reported here are trustworthy. For instance, interview participants did not always adhere to prescribed narratives, give self-serving or self-aggrandizing statements, or take the opportunity to point the finger. Following other post-conflict ethnographers (Fujii 2009; Hinton 2004; Mironko 2007), I take these as reasons for trusting the data despite the constraints of collective and individual memories. Fourth, the research presented in this article points to propaganda as a secondary influence on collective violence; thus, it remains difficult to definitively speak to any degree of causation. If propaganda is entangled in the historical imaginary, cultural knowledge, and emotionally resonant symbols of a community, as this and other post-conflicts studies indicate, then measuring the perlocutionary effect of any propagandist may remain opaque.

Nevertheless, my interviews with former combatants and survivors revealed consistent conditions that insiders identified as significant for propaganda, which cohere with factors identified by recent theorists (e.g., Leader Maynard and Benesch, 2016). These included the widely remembered political-shift that came with state-sponsored ethnicity or political movements associated with ethnoreligious nationalism. Such an identity-imposed politics was remembered as setting the stage for later discursive injustices and criminal speech, which did not instill hatreds or fears but convinced many that conflict and perceived self-defense for themselves, as a targeted categorical group, was unavoidable. As I report elsewhere (Kiper 2018), propaganda in the case of the Yugoslav Wars often prompted would-be fighters to the frontlines, but it was the conditions on the warfront itself and among distinct violence cadres, such as paramilitaries or weekend warriors, that contributed most strongly to atrocities.

[I’ll add one thing though, with the caveat that I’m nowhere near knowledgeable enough to speak authoritatively: it feels to me that a problem with the language/framing used by Kiper here is treating every side/country/group involved in these wars on an equal footing, i.e. as if the nationalistic aspects/patterns among victims of genocidal campaigns like Bosniaks, can be analyzed in the same terms as the genocidal ethno-nationalism that characterizes the Serbian fascists that attacked them, and which they used to gain support for it their crimes back in Serbia]

Another example of genocidal propaganda and discourse is anti-Roma racism in Europe. This is a transnational pattern that runs across the full political spectrum, with a widespread denial that this racist dehumanization and violence even exists (or to be frank, I’m not sure people believe it’s bad even if they acknowledged it…). Both explicitly and implicitly, the Roma are portrayed and described as a form of waste or nuisance instead of a set of poor communities that have been victimized, criminalized and persecuted for decades and centuries in many countries across Europe.

In recent years, we’ve also seen genocidal propaganda and discourse spread through online platforms, in the cases of the genocides: in China against the Uyghurs, in Myanmar against Rohingyas, and in Tigray against Tigrayans; the Islamic State’s online publications also constituted a form of genocidal propaganda (in Iraq and Syria, ISIS targeted Turkmen, the Shabak, Assyrians, Chaldean, Syriac Christians, Yazidis, and other groups; the UN declared genocide was only comitted against the Yazidis, but I’m frankly not a fan of legalistic gatekeeping/formalism).

Where does all of the above leave us with respect to the role of genocidal/atrocity-justifying ideologies and propaganda? Following all the previous groundwork I’ve done (here and in other chapters/sections of this project), here are a few clues/ideas/pistes to merely begin to conceptualize and analyze the role of genocidal propaganda, while emphasizing the general necessity of examining the specifics of each sociohistorical context and looking for concrete mechanisms/processes/relations/patterns rather than presuming a straightforward/linear effect. Following the above-mentioned findings, dehumanization – via ideology and propaganda – needs to be factored in because it clearly does play a signficiant (even if not primary) role, but it’s crucial to contextualize it sociologically, that is paying attention to how its role is conditioned, mediated and differentiated by/through other patterns/relations in the given society at that time (as well as in the longer term, e.g. sociocultural norms or discriminatory categories imposed by colonizers, as in the case of how European “racial science”, including “racial”/”ethnic” categorizations and craniology, contributed directly to the context of the 1994 genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda). Let me quote Luft again:

One possibility, as mentioned above, is that dehumanizing propaganda can alter common perceptions of others’ beliefs, compelling those who might dissent to hesitate to speak out. Even if people do not believe what they hear on the radio, dehumanizing propaganda can increase the perceived risks of verbal and behavioral disagreement with extremists. Alternatively, dehumanizing propaganda can persuade some with already-negative perceptions of others to act violently and then trigger a contagion effect whereby, as a result of social interactions, these people then motivate others to join.

Dehumanizing propaganda can also, quite simply, grant legitimacy to those who put forth violent solutions to social problems, even if it doesn’t convince all listeners. Extreme perspectives can become normalized when dehumanization becomes central to political discourse.

Finally, in my own research, I find that dehumanization is more often an outcome of participation in violence rather than a precursor. In other words, people make difficult decisions about whether or not to participate in genocide based on their access to financial resources, who they’re being asked to kill, their proximity to extremists ordering the violence, and signals sent by local elites. But the more they kill, the easier killing becomes, and this is partly due to shifts in social perception. Although participants in genocide describe reactions that include vomiting, shaking, nightmares, and trauma the first few times they kill, over time, their physical and emotional horror at killing subsides. My research suggests this cognitive adaptation to violence goes hand-in-hand with a transformation in how ordinary killers perceive their victims. Dehumanizing propaganda can help with this process by providing participants with cultural narratives that frame violence as the morally right thing to do, and it can help them overcome their initial resistance to killing neighbors as a result.

Genocidal and atrocity-justifying propaganda therefore not only have a conditioned/mediated/differentiated impact on various groups, but constitute eliminationist politicizations based on pre-existing sociopolitical and cultural conditions, including the legacies of racist, colonialist, patriarchal, and state-constructed categorizations/prejudices/separations/made-up rumors about and dehumanizations of neighbouring communities/countries. Political (incl. military) forces with genocidal intentions – here ideology can play a direct role, in/concerning the most extreme/proactive elements – will use coercion, peer pressure, ethnonationalist or other (e.g. religious) polarizations/othering and conspiracism/moral panics/disinformation to (try to) exploit these latent conditions and orient popular sentiments to achieve the worse barbarisms (systematic killings and torture, forced dispossessions/displacements/labor, concentration/internment/detention/death camps, mass/systematic rape, other forms of abuse, eugenics/sterilizations, etc).

Settler/colonial propaganda is self-explanatorily about justifying and perpetuating settler colonialism (e.g. North and Latin America, Israel/Palestine) and/or colonizations/colonial empires (e.g. Japanese and British empires), and the barbarism, terrorism, exploitation/plunder and genocide committed against Indigenous/colonized communities/societies. A few examples of setler propaganda in the U.S. context have been explored in the Citations Needed podcast (of course I’m sure there’s been a lot more work/research/critique about this, I’ll add it if/when I find sth):

- Episode 139 — Of Meat and Men: How Beef Became Synonymous with Settler-Colonial Domination. Links: pod/transcript.

- Episode 155: How the American Settler-Colonial Project Shaped Popular Notions of ‘Conservation’. Links: pod/transcript.

- Episode 158: How Notions of ‘Blight’ and ‘Barrenness’ Were Manufactured to Erase Indigenous Peoples. Links: pod/transcript.

“Beef. It’s what’s for dinner,” the baritone voices of actors Robert Mitchum and Sam Elliott told us in the 1990s. “We’re not gonna let Joe Biden and Kamala Harris cut America’s meat!” cried Mike Pence during a speech in Iowa last year. “To meet the Biden Green New Deal targets, America has to, get this, America has to stop eating meat,” lamented Donald Trump adviser Larry Kudlow on Fox Business. Repeatedly, we’re reminded that red meat is the lifeblood of American culture, a hallmark of masculine power.

This association has lingered for well over a century. Starting in the late 1800s as white settlers expropriated Indigenous land killing Native people and wildlife in pursuit of westward expansion across North America, the development and promotion of cattle ranching — and its product: meat — was purposefully imbued with the symbolism of dominance, aggression, and of course, manliness.

There’s an associated animating force behind this messaging as well: the perception of waning masculinity in our settler-colonial society. Whether a reaction to the closure of the American West as a tameable frontier in the late 19th century or to the contemporary right’s imagined threats of “soy boys” and a US military that has supposedly gone soft under liberal command, the need to affirm a cowboy sense of manliness, defined and expressed through violence and domination, continues to take the form of consuming meat.

- Episode 172 — The Foundational Myth Machine: Indigenous Peoples of North America and Hollywood. Links: pod/transcript.

George Monbiot is a twat but he wrote a decent piece about how Britain’s legacy of colonial atrocities and genocides were covered up for a long time:

As I’ve mentioned the Holodomor, let’s take a look at another exacerbated famine: in Bengal in 1943-1944. About 3 million people died. As in Ukraine, natural and political events made people vulnerable to hunger. But here too, government policy transformed the crisis into a catastrophe. Research by the Indian economist Utsa Patnaik suggests the inflation that pushed food out of reach of the poor was deliberately engineered under a policy conceived by that hero of British liberalism, John Maynard Keynes. The colonial authorities used inflation, as Keynes remarked, to “reduce the consumption of the poor” in order to extract wealth to support the war effort. Until Patnaik’s research was published in 2018, we were unaware of the extent to which Bengal’s famine was constructed. Britain’s cover-up was more effective than Stalin’s.

The famines engineered by the viceroy of India, Lord Lytton, in the 1870s are even less well-known, though, according to Mike Davis’s book Late Victorian Holocausts, they killed between 12 and 29 million people. Only when Caroline Elkins’s book, Britain’s Gulag, was published in 2005 did we discover that the UK had run a system of concentration camps and “enclosed villages” in Kenya in the 1950s into which almost the entire Kikuyu population was driven. Many thousands were tortured and murdered or died of hunger and disease. Almost all the documents recording these great crimes were systematically burned or dumped at sea in weighted crates by the British government, and replaced with fake files. The record of British colonial atrocities in Malaya, Yemen, Aden, Cyprus and the Chagos Islands was similarly purged.

I also think that in order to be consistent, if the Holodomor is described as a genocide, then so should the Great Irish Famine (An Gorta Mór) of 1845-1852, both being famines in a colonized country that were exacerbated by the colonial state’s policies. Or alternatively, they should both be recognized as empire-led atrocities/injustices without putting them in the “genocide” category. It’s wouldn’t make it any less of an injustice and tragedy, but I just think it has to be consistent because it’s similar contexts. There’s no consensus among historians about calling the Holodmor a genocide, but it is more often considered as such (including by Raphael Lemkin himself) than the Great Irish Famine, for which it’s widely rejected. I think atrocities of this scale, which impacted and traumatized these countries for generations and were clearly exacerbated by colonial powers, can easily be considered genocides because the fact of the matter is that the narrow/legalistic/liberal notions/studies of “genocide” are fundamentally inadequate, depoliticized and eurocentric, as Zoé Samudzi powerfully argued in the 37th issue of The Funambulist (dedicated to this topic and recommended):

Captured by disciplinarity, Genocide Study is the study of necropolitics in which violences are made legible through enumerations, analysis of aggressor goals and intentions, and historiographic comparisons. As a study of people, however, genocide inhabits a different affective register. It is the discovery of the mass graves of Native children at the assimilatory horror shows euphemistically referred to as “residential schools.” It is the pleading for human remains and invaluable artifacts from museum institutions: public institutions that exclude portions of the populous from “the public” so that the bones these excludeds wish to lay to rest can be trapped behind glass and displayed or incarcerated in the archives for study in perpetuity. It is to read in history books that you no longer exist and that your struggle for a self-determining survival was disruptive to “peace” and thus dishonorable. It is your tongue tripping over an alien language that is your birthright; it is watching architectural monstrosities erected on lands stolen from you and your family and your community. It is new military aggressions reiterating long-existing campaigns and occupations; it is diaspora scattered by force, helplessly and worriedly watching assaults and humiliations from afar. It is the denial of phenomenon again and again and again, even as survivors and their descendants present historical records and their own recollections and bodies as evidence. To use Marius Kothor’s own words to answer her question, our “affective response to this history [does] constitute a source of historical knowledge.”

Leaving this brief digression, both the Holodomor and the famines in Ireland and India represent major examples of state/empire-based historical/atrocity denialism/revisionism/cover-up. Neither the USSR/Russia nor England have fully apologized and taken responsibility! And as Niamh Gallagher explained here, the Victorian British press constantly blamed the Irish for the Famine:

The Times argued that Ireland should ‘pay for its own improvement’ (19 August 1846); the apparent unwillingness of its people to do so demonstrated ‘a case of permanent and inveterate national degradation’ (12 October 1847).

Nor was The Times alone in its view. Other publications claimed that the Irish were responsible for their own misfortune. The Economist, founded in 1843, declared on 10 October 1846 that Irish distress was ‘brought on by their own wickedness and folly’.

Imperialist propaganda is simply whatever justifications and rationalizations invading or meddling powers try to spread both within their own country and internationally (not only the targeted country but also to try to sway public opinion around the world). Post-Cold-War examples of course include the Bush administration’s propaganda during the Iraq War (in fact American imperialist-militarist propaganda is constant), and Russian propaganda in the invasion of and war against Ukraine.

Since at least the June 1967 war, Israel has notoriously relied on international/external propaganda and PR to try seducing foreign – and especially Western – publics and specific political/governmental/media/diplomatic circles/elites. A lot of the Zionist myths, as well as audience-tailored PR (which can go as far as sexualising and romanticising female IDF soldiers), are used in order to improve or manage Israel’s image/reputation and justify a) whatever it does to Palestinians, b) the international (diplomatic, economic, military, etc) support that it expects and relies on to maintain their apartheid and occupation. The IDF, along with other branches of the Israeli state and colonial regime, have dedicated PR branches/departments both for internal and external propaganda. We also know that Israel funds anti-BDS journalism, has recruited online troll armies to influence online perceptions, spread disinformation and fake news, use memes and influencer-type content to gain popularity for instance on TikTok, and have convinced major platforms to censor some Palestinian and pro-Palestinian voices.

Moreover, even beyond the propaganda strategies of the Israeli state itself, there is a pro-Israel and anti-Palestinian media bias in the reporting in Western countries, especially Israel’s biggest allies such as the US, Canada, the UK, France and Germany. The New York Times, the BBC, the Washington Post, the Associated Press, CNN and many other mainstream outlets have been and remain guilty of these double standards when covering Israel and Palestine, which is significant given their reach and influence internationally (and in the US specifically, which is obviously the #1 public Israel wants to seduce/manipulate).

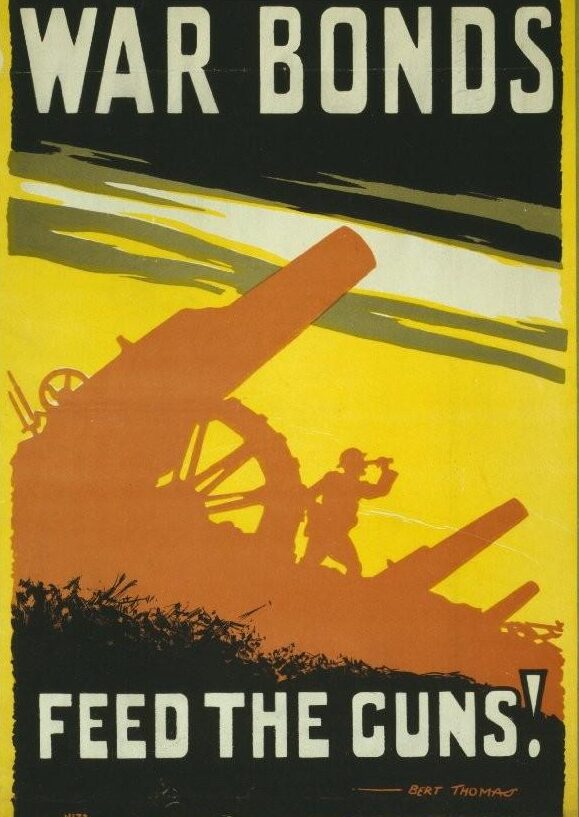

Imperialist, genocidal and settler propaganda all relate closely to what is probably the most famous form of propaganda: war/militarist propaganda. Clearly, these aren’t strictly distinct forms of propaganda but overlapping and interlocked ones that reinforce each other mutually. But propaganda – which obviously already existed, e.g. colonial propaganda and “yellow journalism” – was changed and expanded significantly in the context of World War I, e.g. Woodrow Wilson’s Committee on Public Information. Jordan Kuiper wrote an interesting paper on war propaganda, here’s one basic takeaway:

Oberschall identifies three types of war propaganda that (…) warmongers used to manipulate communities into supporting mass violence and to direct violence cadres into committing atrocities. First, propagandists draw on believable threats in their society to convince communities and combatants that killing adversaries is necessary and justified. Second, propagandists exploit an “information processing model of mass persuasion” to frame mass violence (2010: 11). Put simply, they use narratives, norms, and mental schemas from their culture not only to put the public into a state of fear or outrage, but also to frame the would-be perpetrators as positive and the soon-to-be victims as negative (11–14). Third, the propagandist draws on cultural discourses of in-group innocence, purity, and heroism to make the perpetrators feel victimized but justified in their violence.

It’s also worth noting that contexts of war and explosive chaotic situations (genocides, mass displacements, civil wars, environmental disasters, famines, pandemics, economic crises, sometimes particularly intense elections), truth is “the first casualty”, as the saying goes. Some recent examples obviously include the wars in Syria, Iraq, Ukraine and Israel/Palestine, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic. This is of course to a large extent tied to deliberate propaganda and disinfo by warring parties/states/govts/etc involved in these contexts, but there’s also an intensification of unintentional misinformation, where unverifiable or unreliable rumors/reports get spread out without due diligence on all sides of the conflict/situation (e.g. one nation vs another, vaccine misinformation due to rumors due to poor communication by authorities or healthcare professionals, …).