Originally written: 04.01.2021.

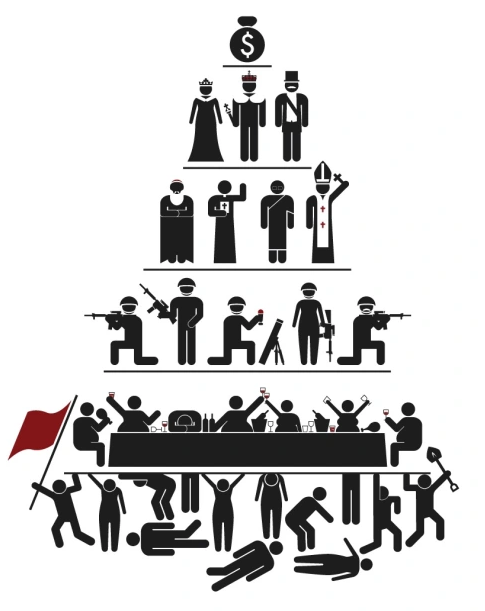

For Marx, the ruling class of a given society – in a specific historical context and/or mode of production – is that minority social group which owns the means of social (re)production. This predominant social position also enables them to dominate the ideological-cultural and state-political realms.

According to Stefano Petrucciani [1], these central aspects of Marx (and Engels’) conception of the ruling class are expressed clearly in the following quotes from The German Ideology:

The conditions under which definite productive forces can be applied are the conditions of the rule of a definite class of society, whose social power, deriving from its property, has its practical-idealistic expression in each case in the form of the State. (…) The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it. (…) the State is the form in which the individuals of a ruling class assert their common interests

Generally, the ruling class is composed of both capitalists and landowners/landlords. For instance, in his article for the New-York Daily Tribune ‘The Future Results of British Rule in India’, he describes the ruling classes of Great Britain as composed of the “artistocracy”, “moneyocracy,” and “millocracy.” As Bertell Ollman explains:

Thus, they include both capitalists and landowners, most of whom belong to the aristocracy. The “millocracy” refers to owners of factories which produce materials for clothing; and the “moneyocracy,” or “finance aristocracy,” refers to bankers and the like, who earn their entrance into the capitalist class as hirers of wage labor and by virtue of their monetary dealings with industrialists.

In his Critique of the Gotha Programme, Marx similarly says that,

In present-day society, the instruments of labor are the monopoly of the landowners (the monopoly of property in land is even the basis of the monopoly of capital) and the capitalists. In the passage in question, the Rules of the International do not mention either one or the other class of monopolists. They speak of the “monopolizer of the means of labor, that is, the sources of life.” The addition, “sources of life”, makes it sufficiently clear that land is included in the instruments of labor.

Throughout his writings, Marx generally uses the category ‘ruling class(es)’ simply to refer to the people who take part in running the country or decide how it should be run. His conception of the ruling class is thus a pretty broad and familiar one. The only thing to keep in mind here is that his definition obviously includes the basic materialist focus on the ruling class’ sources of power, i.e., economic and political domination and ideological hegemony. Let’s now turn to the queen of capitalism herself, la bourgeoisie [2].

The Bourgeoisie.

The original meaning of “bourgeois” and “bourgeoisie” referred to town dwellers, i.e. “those who inhabit the borough” or bourg (French) which is a walled market-town. In other words, the people of the city, including merchants and craftsmen, as opposed to those of rural areas. In feudal France the bourgeoisie was the legal category used for instance in city charters, and this label thus excluded people who lived outside the walls of the city, i.e. mostly the peasantry. During European feudalism (especially France, for the origins of the notion of “bourgeoisie”), it morphed into the more narrow sense of the urban class that possessed certain citizenship, political, economic, and social rights, which, as John Bellamy Foster points out, were “implicitly associated with the property required for trade, that distinguished it from the ordinary urban inhabitant” [3]. We can also add that the “bourgeoisie” in 18th century France was the rich section of the Third Estate, the lowest and largest layer of the socio-political pyramid under the Ancien régime in (Western) Europe. The bourgeoisie rose to be the ruling class – in the proper sense – during the 19th century in Western Europe, with the ‘final birth’ of modern capitalism, coming out of centuries that saw capital being developed mainly through trade (associated with the notion of ‘mercantilism’) and colonialism. Obviously this is just some broad background information helping us for the conception of the bourgeoisie as a class. This is not a rigorous historiographic outline.

As far as I know – and please send me additional info if you know more! – , Marx inherited this concept from Hegel’s notion of bürgerliche Gesellschaft (‘civil/bourgeois’ society’). This refers essentially to the economy, but I’d be interested to know more about it so contact me if have further info on this, especially Hegel’s notion. Here’s what a quick wikipedia search offers

In Karl Marx, the term bourgeois society is used as a translation of the French société bourgeoise and refers to the economic conditions of a society dominated by the bourgeoisie, or in which the capitalist mode of production prevails. 14] Bourgeois society plays a central role especially in Karl Marx’s early writings, which are more influenced by Hegel and German idealism than his mature economic work.[1] Examples of this are Zur Judenfrage, published in 1844, and Das Elend der Philosophie, published in French in 1847 and posthumously translated into German by Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky in 1885. In it, Marx distinguishes bourgeois society from the (political) state, which guarantees equal civil rights and thus creates the legal basis for contractual exchange relations between formally free and equal citizens in bourgeois society.

Obviously this shouldn’t be considered as a very reliable or insightful source, but my goal here is more to focus on the bourgeoisie as such, so I’ll just quote here what I take to be Marx’s own definition of civil society, from the German Ideology:

Civil society embraces the whole material intercourse of individuals within a definite stage of the development of productive forces. It embraces the whole commercial and industrial life of a given stage and, insofar, transcends the state and the nation, though, on the other hand again, it must assert itself in its external relations as nationality and internally must organise itself as state. The term “civil society” emerged in the eighteenth century, when property relations had already extricated themselves from the ancient and medieval community. Civil society as such only develops with the bourgeoisie; the social organisation evolving directly out of production and intercourse, which in all ages forms the basis of the state and of the rest of the idealistic3 superstructure, has, however, always been designated by the same name.

Although he initially used it in this inherited, Hegelian meaning, Marx’s own conception of the bourgeoisie can be said to start in 1843-1844, when he started grounding his analysis of social change in terms of economically defined class forces. He started identifying the bourgeoisie, not as part of the Third Estate, but as the ‘revolutionary’ historical and social force in feudal society, destined to bring about the next society, so to say, in (proto)countries such as France.

Essentially, we can say that the specific meaning of the ‘bourgeoisie’ category for Marx was on the one hand, as the historically specific class responsible for “winning” the social and political conditions necessary for capitalist production. On the other hand, as this transition from the feudal to the capitalist mode of production gradually occurred, it would come to be the new ruling class (or at least, dominant fraction thereof) of modern society, as the very sociological and historical embodiment, or “personnification(s)” as Marx called it, of capital. I’m focusing here on Marx’s views on the bourgeoisie as a social group or category, which does not mean that he simply divided society into classes that fought it out in the ‘class struggle’ arena. For one thing, as I’ll come back to in another installment of this series, the social and structural logic of capital is not nearly the same as the existence of a bourgeois, or capitalist, class owning the ‘means of production’. In other words, it’s important to distinguish capital as a systemic and impersonal force driving the (‘motion’ of) capitalist mode of production, and the socioeconomic categories or sociological “personifications” in the ‘form’ of capitalists who rule over workers on a daily basis. As is obvious to anyone who has read Marx, capital is much broader than the capitalist class, mainly because the former rules over everyone, whereas capitalists exploit and dominate their workers and not the other way around. I’ll leave this issue for now, but it is always crucial to keep this in mind.

Let’s review how Marx talked about the capitalist class throughout his writings. This is what I have been able to gather on my own in a bunch of weeks, so I certainly don’t claim that it is either perfect or exhaustive.

How Marx defines and talks about the Bourgeoisie: General Findings

Before trying to outline the general meaning of the concept of the capitalist class, a few remarks on “how Marx talks about” it might be helpful. Like other classes, such as the proletariat, I would say that his use of this social category consists mostly of analyzing the roles, functions, strategies and actions of a particular collective political “agent of history” and simultaneously, functional social group (or “force”) within the economy in that particular historical context – i.e., mode of production. In other words, in his analyses Marx includes the bourgeoisie as a group which tries (and does) influence the path and evolution of society on both the historical and socioeconomic planes. When it comes to individual capitalists, he usually refers to the behavior and social function(s) of representative of this collective socio-historical agent. At the risk of provoking the ire of anti-orthodox economists, I could say in other words that what matters here is never the individual and concrete capitalists, but rather the “representative agents” or, in Max Weber’s terminology, the “ideal (or pure) type” members, of the bourgeoisie. In addition, the bourgeoisie is most often in the context of its structural and relational opposition to the proletariat; here we can again notice one of the fundamental characteristics of the Marxian conception of class, i.e. that they don’t exist outside of their generalized antagonisms. In several places, Marx mentions the parallel historical development of these two classes as co-existing and mutually determined, though the rising bourgeoisie is generally described as “creating” its own nemesis, as for example in the Communist Manifesto.

Hence on the one hand, the bourgeoisie is conceived of as a collective actor trying to assert itself on the stage of society and history. On the other hand, it is an active force taking part in the economic motion of modern society. The classical definition of the bourgeoisie is that of the owning class under capitalism, i.e. the group monopolizing the private property of the means of production. Although this is certainly an important part, we will see that this famous conception is also flawed, that is, ownership isn’t necessarily the best angle to define the hegemonic position of the bourgeoisie within capitalist social relations. Indeed, recall Marx’s Preface to Capital, Vol. I,

To prevent possible misunderstanding, let me say this. I do not by any means depict the capitalist and the landowner in rosy colors. But individuals are dealt with here only in so far as they are the personification of economic categories, the bearers of particular class-relations and interests. My standpoint, from which the development of the economic formation of society is viewed as a process of natural history, can less than any other make the individual responsible for relations whose creature he remains, socially speaking, however much he may subjectively raise himself above them.

And we find illustrations of this viewpoint in the following passages from Capital, Vol. II:

The movements of capital appear as actions of the individual industrial capitalist in so far as he functions as buyer of commodities and labour, seller of commodities and productive capitalist, and thus mediates the circuit by his own activity. If the social capital value suffers a revolution in value, it can come about that his individual capital succumbs to this and is destroyed, because it cannot meet the conditions of this movement of value. The more acute and frequent these revolutions in value become, the more the movement of the independent value, acting with the force of an elemental natural process, prevails over the foresight and calculation of the individual capitalist, the more the course of normal production is subject to abnormal speculation, and the greater becomes the danger to the existence of the individual capitals. These periodic revolutions in value thus confirm what they ostensibly refute: the independence which value acquires as capital, and which is maintained and intensified through its movement. (196-197) The capitalist casts less value into circulation in the form of money than he draws out of it, because he casts in more value in the form of commodities than he has extracted in the form of commodities. In so far as he functions merely as the personification of capital, as industrial capitalist, his supply of commodity-value is always greater than his demand for it. (…) What is true for the individual capitalist, is true also for the capitalist class. In so far as the capitalist simply personifies industrial capital, his own demand consists simply in the demand for means of production and labour-power. (207) Capital’s changes of form from commodity into money and from money into commodity are at the same time business transactions for the capitalist, acts of buying and selling. The time which these changes of form take for their completion exists subjectively, from the standpoint of the capitalist, as selling time and buying time, the time during which he functions as seller and buyer on the market. Just as the circulation time of capital forms a necessary part of its reproduction time, so the time during which the capitalist buys and sells, prowls around the market, forms a necessary part of the time in which he functions as a capitalist, i.e. as personified capital. It forms a part of his business hours.

This means that beyond – and possibly instead of – the common socialist notion of the bourgeoisie as “the people who own the means of production”, Marx defines it as the class of the representatives, or personifications, of capital. I think it is fair to say that for Marx, the capitalist is a capitalist mostly insofar as he is an abstract member of ‘collective capital’: the economic category of capital is what defines his social position, and not the other way around. Concerning defining the capitalist class as ‘collective capital’, this is explicitly what Marx does in this quote from Capital, Vol. I:

In the history of capitalist production, the establishment of a norm for the working day presents itself as a struggle over the limits of that day, a struggle between collective capital, i.e. the class of capitalists, and collective labour, i.e. the working class.

As far as I know, Marx doesn’t say this in so many words, but what we’ve seen so far already tells us that the capitalist class is the socio-historical force and impersonal collective agent which concretizes the structural domination of capital over society as a whole. As made evident from the above-quoted passage from the Preface, there is a logical primacy of capital over the capitalist: the individual capitalist cannot be made “responsible for relations whose creature he remains”.

In a nutshell, we can see two levels of abstraction (or generality) in Marx’s use of the notion of the capitalist class. Throughout his writings, he either refers to it in a general and historical sense, or in a more specific sense, which most often implies talking about a fraction of it rather than the class as a whole. He tends to rely on this latter sense in his more concrete (i.e. less ‘abstract’) analyses of political and social-economic reality, including for instance his political writings on France. This distinction between a ‘general’ and a ‘specific’ bourgeoisie – or subcategory thereof – is not so straightforward, but it is something I have noticed in reviewing the writings that mention or talk about this class. In his ‘Critique of Political Economy’, Marx seems closer to the latter, more “concrete” sense, although let’s not unnecessarily put this into the two-part box we just created, rather simply point out that in this context he is usually talking about capitalists as economic agents with specific functional roles in the capitalist mode of production.

The capitalist class as a whole is the central – as opposed to the landowners, c.f. the part on this class – oppressing class in bourgeois society, in that it appropriates the surplus product on the backs of the oppressed, producing classes. This surplus product, in this specific mode of production, not only takes a material form, i.e. the means of production (and subsistence) per se, but a ‘value’ form, i.e. surplus value. At the economic level, the main fractions of the capitalist class are the functional representatives of the three forms of capital: its industrial-, money-, and commercial forms. The three corresponding functional types of capitalists will be outlined below, but the conception of these fractions as themselves constituting personifications of these specific forms of capital is expressed clearly in the following from Capital, Vol. II:

The material conditions of commodity production confront him to an ever greater extent as the products of other commodity producers, as commodities. The capitalist must appear to the same extent as a money capitalist, i.e. his capital must function in a greater measure as money capital.

Penguin edition, 1978, p. 118-119.

The most important theoretical writing for understanding Marx’s theoretical (rather than, say, political) conception of the capitalist class, is perhaps Chapter 23 of Capital, Vol. III – “Interest and Profit of Enterprise” [4]. This will help us define more clearly what capitalists are, as well as the aforementioned subdivisions, but also some issues around the ownership and ‘use’ of capital, notably the question of supervision and management. The reason behind the fact that Marx “only” arrives at a more detailed discussion of the capitalist class in Volume Three is highlighted by Heinrich, who also mentions some of the issues and themes we’re going to talk about:

The question of who belongs to what class in a structural sense also cannot be determined according to formal properties, such as the existence of a wage-relationship, but only by the position occupied within the process of production. More precisely: it can only be determined at the level of the “process of capitalist production as a whole” that Marx arrives at in the third volume, where the unity of the processes of production and circulation is already assumed (…). At this level, it is clear that the ownership or non-ownership of means of production is not the only decisive criterion concerning class affiliation. The chairman of the board of a corporation might formally be a wage-laborer, but in fact he is a “functioning capitalist”: he disposes of capital (even if it is not his personal property), organizes exploitation, and his “payment” is not based upon the value of his labor-power, but on the profit produced.

An Introduction to the Three Volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital, p. 193.

More precisely, there is a straightforward reason for this: in Capital, Vol. III, Marx outlines his conception of the division of surplus value, which implies addressing the division of labor among those who appropriate it (directly or indirectly), and therefore examining the functional roles already mentioned above.

Marx draws a distinction between what he calls functioning capitalists and moneyed capitalists, based on “how” the capital they respectively represent “functions”. This is outlined as a way to introduce another important notion: gross profit (total average profit) isn’t simply appropriated as a whole by the capitalist, but divided into interest and profit of enterprise. The latter is the share of (total) profit that goes to the functioning – or “active” – capitalist: the remaining profit once repayment to the lender has been taken care of. Marx defines the functioning capitalist as “[representing] capital only as functioning capital”:

He is its personification in so far as it functions, and it functions in so far as it is productively invested in industry or trade, and he performs through his use of it the operations prescribed by the line of business in which he is employing his capital.

(p. 475)

The reason this capitalist recognizes profit of enterprise as his part of the total profit is that his own share “necessarily appears to him as the product of capital in its actual functioning” (p. 475), that is, capital in its own reproduction process (p. 476), which is the production of value and surplus-value. As Marx puts it, this profit of enterprise “appears to derive exclusively from the operation or functions that he performs with the capital in the reproduction process, especially therefore the functions that he performs as an entrepreneur in industry or trade” (p. 476). By contrast, the moneyed capitalist appropriates the ‘interest’ part of gross profit, without intervening himself in the reproduction process – i.e. production and circulation – and hence appropriating a return on capital that is not the result of capital “functioning as capital”.

Marx starts by assuming that the functioning capitalist doesn’t own the capital he uses in the production process, in order to clearly define these two functional modes of appearance of the subdivision of gross profit (i.e. interest and profite of enterprise). The active capitalist is thus presumed to be a borrower to the moneyed capitalist, so that we can see that their relation lies outside (before and after) the production (and circulation) process: it is purely a legal transaction conditioned upon the repayment, with interest, of the capital initially advanced. The moneyed capitalist grounds his economic position – how he gets revenue – in interest-bearing capital, by appropriating in the form of interest a part of the profit that was produced by using the capital lent to the active capitalist: “The interest that he pays to the lender appears therefore as the part of the gross profit that accrues to property in capital as such” (p. 476).

Marx sums up what we’ve seen so far by talking of a quantitative division leading to a qualitative one:

… once the merely quantitative division of gross profit between two different persons with different legal titles to the same capital and hence to the profit it produces, turns into a qualitative division for the productive capitalist, in so far as he acts with borrowed capital, and for the moneyed capitalist, in so far as he does not apply his capital himself, one part of the profit appears in ond of itself as the fruit that accrues to capital in one capacity, as interest, while the other part appears as a specific fruit of capital in an opposite capacity, and hence as profit of enterprise; the one being the simple fruit of property in capital, the other being the fruit of the mere functioning and process of capital, as the fruit of capital in process or of the functions that the productive capital exercises.

(p. 477)

Moreover, Marx tells us that the aforementioned initial assumption doesn’t actually matter in the end. Here’s one out of two passages on this, which comes right after the previous one:

This mutual ossification and autonomisation of the two parts of the gross profit, as if they derived from two essentially separate sources, must now be fixed for the entire capitalist class and the total capital. This is true irrespective of whether the capital applied by the active capitalist is borrowed or not, or whether or not the > capital appropriated by the < moneyed capitalist is used by him or not. The profit on any capital, and thus also the average profit based on the equalisation of capitals among themselves, breaks down or is divided into two qualitatively distinct, mutually autonomous and independent parts, interest and profit of enterprise, which are both determined by specific laws. The capitalist who works with his own capital, as well as the one working with borrowed capital, divides his gross profit into interest that accrues to him as owner, as lender of his own capital to himself, and profit of enterprise, which accrues to him as a functioning capitalist. It becomes a matter of indifference, as far as this division is concerned > (from the qualitative point of view) < whether the capitalist really does have to share with another or not. The person who employs capital, even if he works with his own capital, breaks down into two people, the mere owner of capital and its user; his capital itself, with respect to the categories of profit that it yields, breaks down into owned capital, capital outside the production process, which yields an interest in itselfi, and capital in the production process, which yields profit of enterprise as capital in process.

(p. 477)

…this division of gross profit into interest and profit of enterprise, once it becomes a qualitative > division for the productive capitalists who work with borrowed capital, < receives this character of a qualitative division for the total capital and the capitalist class as a whole.

(p. 478)

As @postcyborg helpfully summarized (on twitter) [5]:

His point here is that the division of profit depends on the fundamental function of capital in production, but that this structurally presupposes money-capital [note: i.e. the latter allows the whole process to continue], and so the separation forms an uneasy unity. It is capital because it posits surplus-value production (i.e. commands unpaid labor) and so depends crucially on the functioning capitalist, but any functioning capitalist depends crucially in turn on money-capital to advance, whether as an interest-bearing loan or their own accumulation. Capitalists are such in order to make money, through whatever means, even the functioning industrial capitalists. So he semms to be placing “both perspectives” of accumulation side by side in their mutual and contradicting dependence.

@postcyborg is here highlighting what Marx is saying a few pages later:

Just as the transformation of money (value in general) into capital is the constant result of the capitalist production process, so its existence as capital is in the same way the constant presupposition of this process. That is to say, through its ability to be transformed into means of production it always commands unpaid labour and hence transforms the production and circulation process of commodities into the production of surplus-value for its possessor. Interest therefore simply expresses the fact that value in general – objectified labour in its general social form – value that assumes the form of means of production in the actual production process, confronts living labour-capacity (labour-power) as an autonomous power and is the means of appropriating unpaid labour, and that it is this power in that it confronts the worker as the property of another person. On the other hand, however, this antithesis to wage-labour is obliterated in the form of interest; for interest-bearing capital as such does not have wage-labour as its opposite but rather capital > to the extent that it is functioning; < it is the capitalist actually functioning in the reproduction process whom the lending capitalist directly confronts, and not the wage-labourer who is expropriated from the means of production precisely on the basis of capitalist production. Interest-bearing capital is capital as property as against capital as function. But to the extent that capital does not function, it does not exploit workers and does not come into opposition with labour.

(p. 481-482)

In an important contribution to his overall theory of class, Marx is here talking about how two issues combine to make the study of class relations difficult. On the one hand, capitalist social relations are systematically mystified, masking the real relations of power, exploitation and domination: just as the “fetishism” of money as an autonomous economic instrument hides the class relations and the exploitation of labour that it actually represents in the capitalist mode of production, the division of profit into two (seemingly) independent forms reifies the social relations between different capitalists as well as between those and labourers. However, on the other hand, the autonomisation of these elements – money and divided parts of total profit – is in fact a “real thing”, as opposed to a mere illusion: this is what some people call ‘real abstractions’, when reified products of the capitalist mode of production actually turn out to represent real social dynamics. The original example is about Marx’s theory of “commodity fetishism”: on the one hand the fetishism (i.e. ascribing extraordinary or supernatural powers to specific objects) of the commodity masks the social relations at its source, but on the other there is in real capitalist social life a mode of socialisation wherein social relations between people are subsumed under, and take the form of, relations between things – commodities. Marx’s analytical method is therefore to highlight the illusory and reified character of economic categories that fundamentally mask the social and class relations behind them, and thus both free our theoretical understanding from the illusions of bourgeois political economy and pinpoint the underlying social and class relations that crucially determine these economic phenomena.

Here are some arguments by Marx that follow this thought process, concerning what we saw above. Notice how he contrasts appearances and the actual state of affairs:

In the actual process, the functioning capitalist represents capital against the wage-labourers as the property of others and the moneyed capitalist, as represented by the functioning capitalist, participates in the exploitation of labour. That it is only as the representative of the means of production towards the workers that the active capitalist can exercise his functions, can have the workers work for him or can have the means of production function as capital, is something that is forgotten in the face of the opposition between the function of capital in the reproduction process and mere ownership of capital outside the reproduction process.

(p. 483)

The social form of capital devolves upon interest, but interest expressed in a neutral and indifferent form, the economic function of capital devolves on profit of enterprise, but with the specifically capitalist character of this function removed.

(p. 485)

… the ossification and autonomisation of both parts vis-à-vis one another makes the actual state of affairs appear in inverted form in the mind. Profit (which is itself already a transformed form of surplus-value) does not appear as the presupposed unity, the sum total of unpaid labour, which is divided into interest and profit of enterprise. Instead of this, interest and profit of enterprise appear as independent magnitudes, which form profit, gross profit, when added together. Since the relation to surplus-value, and therefore the real relationships of capital to wage-labour, has now been extinguished in each of these parts, considered separately, so also does this apply to profit itself, to the extent that it presents itself as a mere addition, as a supplementary quantity of these given magnitudes which have been determined independently and are apparently presupposed to it.

(p. 485-486)

This perspective is also used by Marx in order to address the issue of the capitalist’s “labor”, or the work he or she has to do to manage the (re)production process; and inevitably, the question of remuneration for this work is dealt with as well. This is another source of insights located in this chapter. The argument is briefly summed up here:

The confusion between profit of enterprise and the wages of superintendence originally arose from the antithetical form that the surplus of profit over interest assumes in opposition to that interest. It was developed further with the apologetic intention of presenting profit not as surplus-value – unpaid labour – but as the capitalist’s own wage.

(p. 491)

According to Marx, all modes of production ‘based on the class opposition’, due to the ‘antithetical character’ of the relationship between oppressing and oppressed classes require what he calls the “labour of superintendence and direction” [p. 488]: directing and controlling the production of the product and surplus product from above, to ensure that this process reaches the expected output and thus makes economic activity (sales, for instance) and – in the end – surplus appropriation possible and more or less guaranteed. He quotes some observations by Aristotle – some kind of ancient ‘debate me bro’-type dude as far as I’m aware – to explain this, and concludes the following:

What Aristotle is saying, in blunt terms, is that domination, in the economic domain as well as the political, imposes on those in power the function of dominating, which means, in the economic domain, that apart from buying and selling (which is the job of the villicus) they must know how to consume labour-capacity. And he adds that this labour of superintendence is not a matter of very great moment, which is why the master leaves the ‘honor’ of this drudgery to an overseer, as soon as he is wealthy enough.

(p. 487-488)

But wait, there’s more.. This ‘superintendence’ work has a specific ideological role as well:

… this function, arising from the servitude of the direct producer, is made into a justification of that relationship itself, and the exploitation and appropriation of the worker’s unpaid labour is presented as the wage due to the owner of capital.

(p. 488)

Finding this section was really interesting to me, because perhaps as yourself too, I have sometimes wondered how to respond to or comprehend the issue of the difference between the “capitalist” owner(s) versus the “manager” in a capitalist firm. In other words: is a CEO who’s paid a salary a capitalist? The common answer from apologetic bourgeois perspectives would separate these two, making the shareholders the “real” capitalists – because they are the ‘actual owners’, whereas the manager is merely considered a highly paid professional. Fortunately, it turns out Marx addressed this whole question in Book III, even though there are probably some more issues and questions we would need to tackle from today’s perspective. Now let’s return to Marx’s argument.

The labour of superintendence and direction, insofar as it arises from the antithetical character of the relationship, the domination of capital over labour (and is therefore common to all modes of production which, like the capitalist one, are based on class opposition) is also directly and inseparably linked, on the basis of the capitalist mode of production, with the productive functions that all combined social labour assigns to particular individuals as their special work. The wages of an επἰροπος, or manager, or régisseur (as he was known in feudal France) become completely separated from profit and even take the form of wages for skilled labour, as soon as the business is conducted on a sufficiently large scale for such a manager to be paid, even though the productive capitalists are still a long way from ‘pursuing public affairs of philosophy’ “

(p. 488-489)

Tellingly, Marx uses a quote from a lawyer defending slavery in the US, in order to show this tie between economic domination and its ideological justification (see also the whole quote from the lawyer, above on the same page):

The wage-labourer, like the slave, must have a master, to make him work and govern him. And once this relationship of domination and servitude is assumed, it is quite in order for the wage-labourer to be compelled to produce his own wages, and, on top of this, the wages of superintendence, a compensation for the work of dominating and supervising him, in order ‘to afford to that master a just compensation for the labour and talent employed in governing him and rendering him useful to himself and to the society in which the society he lives’!

(p. 488)

It’s never as clear as when it comes from the horse’s mouth, isn’t it? [Heartfelt apologies to the beautiful horse community, which, like the pig community when we insult those damned cops – ACAB -, get scandalously slandered and denigrated… Horses and pigs are cute and smart, and they are our friends so we should cherish their reputation (- the PC Police, Manhattan, January 2021)]

Here’s the last bit I want to quote in this first section, from a footnote that I found really interesting [6]:

Capitalist production has itself brought it about that the labour of direction readily available, quite independently of the ownership of capital. It has therefore become superfluous for this labour of direction to be performed by the capitalist. A music director need in no way be the owner of the instruments in his orchestra, nor does it form part of his function as a conductor that he should have anything to do with the ‘wages’ of the other musicians. Cooperative factories provide the proof that the capitalist has become just as superfluous as a functionary in production as he himself, from his superior vantage point, finds the landlord to be. In so far as the work of the capitalist does not arise from the production process as a capitalist process, i.e., does not come to an end with capital itself; in so far as it is not a name for the function of exploiting the labour of others; in so far therefore as it arises from the form of labour as social labour, from the circulation, etc., it is just as independent of capital as is this form itself, once it has burst out of its capitalist shell. To say that this labour, as capitalist labour, is necessarily the function of the capitalist means nothing more than the vulgarian cannot conceive of the existence of these forms, developed in the womb of the capitalist mode of production, in separation from, and freed from, their antithetical character. Vis-à-vis the moneyed capitalist, the productive capitalist is a worker, but his worker is that of capitalist, i.e., an exploiter of the labour of others. The wage of this labour is exactly equal to the quantity of others’ labour appropriated, in other words it depends directly upon the degree of exploitation, not on the degree of exertion that this exploitation costs to the capitalist, and which he may pay to a general manager.

(note n°39, p. 489)

I will provide a general summary at the end of this article, so let’s continue directly with the historical section.

History

Although he didn’t keep referring to this afterwards, Marx’s suggests in The Poverty of Philosophy that,

[in] the bourgeoisie we have two phases to distinguish: that in which it constituted itself as a class under the regime of feudalism and absolute monarchy, and that in which, already constituted as a class, it overthrew feudalism and monarchy to make society into a bourgeois society.

Realistically, these two phases were -more or less- the ones Marx focused on. He largely didn’t focus on a third moment we could mention and which we’ve known since then, that of the “hegemonic” phase of the capitalist class. I believe it is fair and accurate to say that Marx mostly studied on one hand the “proto-history” of the bourgeoisie, and, on the other, its rise in the 18th and – especially – 19th centuries. Let us keep in mind that modern capitalism as the predominant social system is relatively recent, that is, in the form(s) we’ve known since the second half of the 19th century. This is not the same as commercial and colonial capitalism preceded it. Marx’s second phase does have a lot in common with the hegemonic phase that asserted itself during the 20th century. In other words, it’s not like the rise of the bourgeoisie to the position of ruling class is completely different from how it is in the historical period during which it is the hegemonic class ruling over society. In the end, this periodisation is mostly useful as a pragmatic way to address Marx’s views, whether or not it is relevant for him or for us in the broader scheme of things (it probably isn’t).

-

- The Formation of the Bourgeoisie as a Class

In his introduction to Marx’s Precapitalist economic formations (taken from the Grundrisse), Eric Hobsbawm briefly summarized this first phase of the historical bourgeoisie:

The transition from feudalism to capitalism, however, is a product of feudal evolution. It begins in the cities, for the separation of town and country is the fundamental and, from the birth of civilisation to the nineteenth century, constant element in and expression of the social division of labour. Within the cities, which once again arose in the Middle Ages, a division of labour between production and trade developed, where it did not already survive from antiquity. This provided the basis of lang-distance trade, and a consequent division of labour (specialisation and production) between different cities. The defence of the burghers against the feudalists and the interaction between the cities produced a class of burghers out of the burgher groups of individual towns.

It is largely in some of his earlier works that Marx mentioned and described this genesis of the bourgeoisie as a ‘class in itself’: there are general passages in the German Ideology (co-written with Engels), the Poverty of Philosophy and the Communist Manifesto. As often with Marx, we are left wondering whether these views were subsequently taken for granted, during the so-called ‘mature’ period when he developed his more sophisticated critical theoretical framework. I haven’t found much about this first phase in his Grundrisse, which however some passages on the second phase we’ll look at next. Be that as it may, here are some extracts that were selected because they seemed relevant.

The most succinct outline by Marx of the formation of the capitalist class is in the German Ideology, and will remind you of Hobsbawm’s summary:

In the Middle Ages the citizens in each town were compelled to unite against the landed nobility to save their skins. The extension of trade, the establishment of communications, led the separate towns to get to know other towns, which had asserted the same interests in the struggle with the same antagonist. Out of the many local corporations of burghers there arose only gradually a burgher class. The conditions of life of the individual burghers became, on account of their contradiction to the existing relationships and of the mode of labour determined by these, conditions which were common to them all and independent of each individual. The burghers had created the conditions insofar as they had torn themselves free from feudal ties, and were created by them insofar as they were determined by their antagonism to the feudal system which they found in existence. When the individual towns began to enter into associations, these common conditions developed into class conditions. The same conditions, the same contradiction, the same interests necessarily called forth on the whole similar customs everywhere.

In Poverty of Philosophy, Marx talks about feudalism, saying that ‘serfage (…) contained all the germs of the bourgeoisie’:

Feudal production also had two antagonistic elements which are likewise designated by the name of the good side and the bad side of feudalism, irrespective of the fact that it is always the bad side that in the end triumphs over the good side. It is the bad side that produces the movement which makes history, by providing a struggle. If, during the epoch of the domination of feudalism, the economists, enthusiastic over the knightly virtues, the beautiful harmony between rights and duties, the patriarchal life of the towns, the prosperous condition of domestic industry in the countryside, the development of industry organised into corporations, guilds and fraternities, in short, everything that constitutes the good side of feudalism, had set themselves the problem of eliminating everything that cast a shadow on this picture—serfdom, privileges, anarchy—what would have happened? All the elements which called forth the struggle would have been destroyed, and the development of the bourgeoisie nipped i n the bud. One would have set oneself the absurd problem of eliminating history.

Marx writes in “Moralising Criticism and Critical Morality” that “absolute monarchy appears in those transitional periods when the old feudal estates are in decline and the medieval estate of burghers is evolving into the modern bourgeois class, without one of the contending parties having as yet finally disposed of the other”.

In the Communist Manifesto, the bourgeoisie is described as an oppressed class under feudalism (“under the sway of the feudal nobility”), and as a revolutionary class destined to lead and fight for the transition from the latter to modern capitalist society. Here are the passages I’ve found:

… the means of production and of exchange, on whose foundation the bourgeoisie built itself up, were generated in feudal society. The medieval burghesses and the small peasant proprietors were the precursors of the modern bourgeoisie. From the serfs of the Middle Ages sprang the chartered burghers of the earliest towns. From these burgesses the first elements of the bourgeoisie were developed. The serf, in the period of serfdom, raised himself to membership in the commune, just as the petty bourgeois, under the yoke of feudal absolutism, managed to develop into a bourgeois.

-

- The “Revolutionary” Bourgeoisie: Overthrowing the Feudal Order and Making ‘Society Into Bourgeois Society’

There is far more material on the second phase, during which the bourgeoisie “[made] society into bourgeois society”. Moreover, Marx talks about this historical process not only in his earlier writings, but also in “mature” works such as Capital, Vol. I [7]. Marx’s analysis seems to me to focus simultaneously on the development of both the bourgeoisie as an oppressing class, and that of the new capitalist mode of social organization, i.e. bourgeois society as such. In other words, the formation of the bourgeois class is to a significant extent undifferentiated from that of the genesis of capitalist social relations and bourgeois society in general.

As is well known, Marx viewed the bourgeoisie as the class leading the rise of capitalist society, from its origins as merchants in the Middle Ages to taking power gradually in the 19th century. It isn’t the only class involved in this transition, since social and political struggles involving particularly the peasantry play a major role in this centuries-long process. Nonetheless, as famously formulated in the Communist Manifesto, for Marx and Engels this bourgeois class, from oppressed class under the feudal nobility to oppressing class in the capitalist mode of production, played a “revolutionary” role [8] in overthrowing one social order and bringing about the new one.

What stands out the most in my opinion is that, similarly to the role of the proletariat in bringing about communism – facilitated by capitalism’s own contradictions that supposedly create the very conditions of its overcoming – , the bourgeoisie doesn’t only fight deliberately as a specific agent for reaching political and social hegemony, but seems for Marx to embody and personify this massive social transformation, this revolution of social relations and conditions. This is what I meant by the bourgeois class and capitalist society – their historical genesis – are largely “undifferentiated”.

The paradox here is that, as a consequenc of this, one can easily get the impression – especially in the Communist Manifesto – that the bourgeoisie “made” capitalism, so to say. While the above remarks aren’t invalidated, the following statement must therefore be kept in mind against any messianic view of the bourgeoisie as the ‘creator’ of bourgeois society:

The knights of industry, however, only succeeded in supplanting the knights of the sword by making use of events in which they played no part whatsoever.

(Capital I, p. 875)

For this subsection, instead of reviewing his works “one by one”, I decided to provide an overview of his interpretation of this topic as a whole. The historical transition from feudal to bourgeois society – and here we are mainly concerned with the role of the capitalist class in this process – is briefly summed up by Marx in the following extract from a letter to the editor of a Russian journal:

The chapter on primitive accumulation does not pretend to do more than trace the path by which, in Western Europe, the capitalist order of economy emerged from the womb of the feudal order of economy. It therefore describes the historic movement which by divorcing the producers from their means of production converts them into wage earners (proletarians in the modern sense of the word) while it converts into capitalists those who hold the means of production in possession. In that history, “all revolutions are epoch-making which serve as levers for the advancement of the capitalist class in course of formation; above all those which, after stripping great masses of men of their traditional means of production and subsistence, suddenly fling them on to the labour market. But the basis of this whole development is the expropriation of the cultivators. “This has not yet been radically accomplished except in England….but all the countries of Western Europe are going through the same movement,” etc. (Capital, French Edition, 1879, p. 315).

(Marx’s letter to the Editor of Otecestvenniye Zapisky, November 1877)

Thus we see that the bourgeoisie, once formed as a “class in itself” (under feudalism), is destined by historical and social-structural conditions to gradually rise to the level of the central oppressing class of capitalist society as a whole. It is created as such by these structural-historical conditions, and to some extent creates them by realizing – in ways that might differ between the concrete contexts in question – its potential as a socio-historical agent conditionned to bring about the new capitalist social order. At the social level, it becomes the representative of all private property:

The bourgeoisie itself, with its conditions, develops only gradually, splits according to the division of labour into various fractions and finally absorbs all propertied classes it finds in existence (while it develops the majority of the earlier propertyless and a part of the hitherto propertied classes into a new class, the proletariat) in the measure to which all property found in existence is transformed into industrial and commercial capital.

(German Ideology)

At the political level, it must gradually appropriate for itself the political state in order to make it defend its (class) interests:

By the mere fact that it is a class and no longer an estate, the bourgeoisie is forced to organize itself no longer locally, but nationally, and to give a general form to its average interests. Through the emancipation of private property from the community, the state has become a separate entity, alongside and outside civil society; but it is nothing more than the form of organisation which the bourgeois are compelled to adopt, both for internal and external purpose, for the mutual guarantee of their property and interests.

(German Ideology)

As he wrote in the Communist Manifesto, we must understand this historical process as the parallel or simultaneous development of both the social and the political sway of the bourgeoisie: “Each step in the development of the bourgeoisie was accompanied by a corresponding political advance of that class.” The political process will be looked at in the next section, so far now let’s just point out that Marx’s writings on French political events represents his analysis of the complex journey of the bourgeoisie (and fractions thereof) to reach political hegeomy. Engels explains why in one of the footnotes added to the 1882 English Edition of the Communist Manifesto: “Generally speaking, for the economical development of the bourgeoisie, England is here taken as the typical country, for its political development, France.”

As was mentioned in the 1877 letter, the historical root of bourgeois society, and therefore of the conditions of the bourgeoisie’s supremacy, was the process of expropriation of producers (and especially, ‘agricultural producers’). Marx matches Engels’ comment about England as the “typical” country when he says that,

The history of this expropriation assumes different aspects in different countries, and runs through its various phases in different orders of succession, and at different historical epochs. Only in England, which we therefore take as one example, has it the classic form.

(Capital I)

While the methodological choice of using England as the “purest” case study might be questioned from our own point of view, this passage is really fundamental because it doesn’t merely provide further evidence – in addition to the aforementioned 1877 letter as well as the 1881 correspondence with Vera Zasulich – that Marx’s understanding of the historical development of societies isn’t unilinear or derived from a “Western” universal model. As far as we’re concerned here, it could be argued that while expropriation and ‘primitive accumulation’ are probably, from this viewpoint, a necessary part of the historical trajectory toward modern capitalism, within this long-term process there might be a variety of forms of the bourgeoisie’s history and roles. But let’s not get carried away.

Another fundamental notion is expressed elsewhere in Capital I (in the Penguin edition: p. 899-900). First, Marx tells us that “it is not enough” that expropriation and primitive accumulation have created a social context in which “the conditions of labour” are concentrated in the hands of capital, nor that the propertyless “grouped masses of men” are “compelled to sell themselves voluntarily”. Rather, the “advance of capitalist production develops a working class which by education, tradition and habit looks upon the requirements of that mode of production as self-evident natural laws.” Once (‘advanced’) capitalism has been established, the process of production “breaks down all resistance”:

the mute compulsion of economic relations seals the domination of the capitalist over the worker [der stumme Zwang der ökonomischen Verhältnisse besiegelt die Herrschaft des Kapitalisten über den Arbeiter]. Extra-economic, immediate violence [Außerökonomische, unmittelbare Gewalt] is still of course used, but only in exceptional cases. In the ordinary run of things, the worker can be left to the “natural laws of production,” i.e., it is possible to rely on his dependence on capital, which springs from the conditions of production themselves, and is guaranteed in perpetuity by them.

(quoted – using the same edition, p. 899 – in Søren Mau, Mute Compulsion. A Theory of the Economic Power of Capital, University of Southern Denmark, 2019, p. 13)

This concerns the historical moment when capitalism is “fully developed”, but it was necessary to mention this – although I admit this is also in part self-indulgence on my part, I really liked Mau’s thesis – because Marx continues right after this with the following passage, which concerns us more directly here [8]:

It is otherwise during the historical genesis of capitalist production. The rising bourgeoisie needs the power of the state, uses it to ‘regulate’ wages, i.e., to force them into the limits suitable for making a profit, to lengthen the working day, and to keep the worker himself at his normal level of dependence. This is an essential aspect of so-called primitive accumulation.

(Capital I, p. 900)

As he puts it later on, this brutal process consisted in “the forcible creation of a class of free and rightless proletarians, the bloody discipline that turned them into wage-labourers, the disgraceful proceedings of the state which employed police methods to accelerate the accumulation of capital by increasing the degree of exploitation of labour” (Capital I, p. 905).

To conclude this section, I will sum up two relevant chapters from Capital I, namely “The Genesis of the Capitalist Farmer” (Chap. 29) and “The Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist” (Chap. 31). The expropriation of the agricultural producer creates at first the modern class of great landed proprietors, but in the longer view – ‘a slow process evolving through many centuries’ [9] – there is the genesis of modern capitalist farmers from ‘serfs’ and ‘small-scale peasant proprietors’ [10]. For various reasons – such as the ‘agricultural revolution’ and other opportunities – which Marx mentions in this chapter (29), this middle layer of feudal society managed to accumulate wealth up to the point where their class interests became congruent with the dynamic of capital within this new mode of production. The birth of the industrial capitalist is rather different (although Marx doesn’t deny that here again there’s a certain diversity of scenarios):

Doubtless many small guild-masters, and yet more independent small artisans, or even wage labourers, transformed themselves into small capitalists, and (by gradually extending exploitation of wage labour and corresponding accumulation) into full-blown capitalists. In the infancy of capitalist production, things often happened as in the infancy of medieval towns, where the question, which of the escaped serfs should be master and which servant, was in great part decided by the earlier or later date of their flight. The snail’s pace of this method corresponded in no wise with the commercial requirements of the new world market that the great discoveries of the end of the 15th century created.

(MIA link)

The Middle-Ages ‘handed down’ two forms of capital that would make the genesis of industrial capital possible: ‘merchant’s capital’ and ‘usurer’s capital’. This chapter goes into much more detail than I want to cover here, describing a whole series of what Marx dark-ironically calls “idyllic proceedings”, including genocidal exploitation of African slaves and Indigenous populations and the colonial looting of East Asia. To sum up the rest of this chapter – which I highly recommend reading for yourself, since Marx develops in further detail everything just mentioned in passing here – let’s finally quote Marx once again before moving on to the last section of this inquiry:

The different momenta of primitive accumulation distribute themselves now, more or less in chronological order, particularly over Spain, Portugal, Holland, France, and England. In England at the end of the 17th century, they arrive at a systematical combination, embracing the colonies, the national debt, the modern mode of taxation, and the protectionist system. These methods depend in part on brute force, e.g., the colonial system. But, they all employ the power of the State, the concentrated and organised force of society, to hasten, hot-house fashion, the process of transformation of the feudal mode of production into the capitalist mode, and to shorten the transition. Force is the midwife of every old society pregnant with a new one. It is itself an economic power.

Politics

There is actually too much content that could be put in this section, so it doesn’t make sense here to review Marx’s writings from start to finish. What’s more, I am sincerely becoming tired of this article, so hopefully you’ll forgive me for shortening what is already a painfully long investigation.

The best entry point and summary of the political dimension of the bourgeoisie in Marx’s writings, seems to me to be the following very long passage from his writings on the Paris Commune. I have chosen here to use the version from the Second Draft, but it is necessary to also read the corresponding section from the published version.

The centralized state power, with its ubiquitous organs of standing army, police, bureaucracy, clergy and magistrature, organs wrought after the plan of a systematic and hierarchic division of labour, dates from the days of absolute monarchy when it served nascent middle class society as a mighty weapon i n i ts struggles for emancipation from feudalism. The French Revolution of the 18th century swept away the rubbish of seigniorial, local, townish and provincial privileges, thus clearing the social soil of its last medieval obstacles to the final superstructure of the state. It received its final shape under the First Empire, the offspring of the Coalition wars of old, semifeudal Europe against modern France. Under the following parliamentary regimes, the hold of the governmental power, with its irresistible allurements of place, pelf, and patronage, became not only the bone of contention between the rival factions of the ruling classes. Its political character changed simultaneously with the economic changes of society. At the same pace that the progress of industry developed, widened and intensified the class antagonism between capital and labour, the governmental power assumed more and more the character of the national power of capital over labour, of a political force organized to enforce social enslavement, of a mere engine of class despotism. On the heels of every popular revolution, marking a new progressive phase i n the march (development) (course) of the struggle of classes, (class struggle), the repressive character of the state power comes out more pitiless and more divested of disguise.

The Revolution of July, by transferring the management of the state machinery from the landlord to the capitalist, transfers it from the distant to the immediate antagonist of the working men. Hence the state power assumes a more clearly defined attitude of hostility and repression in regard to the working class. The Revolution of February hoists the colours of the “social Republic”, thus proving at its outset that the true meaning of state power is revealed, that its pretence of being the armed force of public welfare, the embodiment of the general interests of societies rising above and keeping in their respective spheres the warring private interests, is exploded, that its secret as an instrument of class despotism is laid open, that the workmen do want the republic, no longer as a political modification of the old system of class rule, but as the revolutionary means of breaking down class rule itself.

In view of the menaces of “the Social Republic” the ruling class feels instinctively that the anonymous reign of the parliamentary republic can be turned into a jointstock company of their conflicting factions, while the past monarchies by their very title signify the victory of one faction and the defeat of the other, the prevalence of one section’s interests of that class over that of the other, l and over capital or capital over l and.

In opposition to the working class the hitherto ruling class, in whatever specific forms it may appropriate the labour of the masses, has one and the same economic interest, to maintain the enslavement of labour and reap its fruits directly as landlord and capitalist, indirectly, as the state parasites of the landlord and the capitalist, to enforce that “order” of things which makes the producing multitude, “a vile multitude” serving as a mere source of wealth and dominion to their betters.

Hence Legitimists, Orleanists, Bourgeois Republicans and the Bonapartist adventurers,eager to qualify themselves as defenders of property by first pilfering it, club together and merge into the “Party of Order”, the practical upshot of that revolution made by the proletariat under enthusiastic shouts of the “Social Republic”. The parliamentary republic of the Party of Order is not only the reign of terror of the ruling class. The state power becomes in their hand the avowed instrument of the civil war in the hand of the capitalist and the landlord, not their state parasites, against revolutionary aspirations of the producer. Under the monarchical regimes the repressive measures and the confessed principles of the day’s government are denounced to the people by the fractions of the ruling classes that are out of power, the opposition’s ranks of the ruling class interest the people in their party feuds, by appealing to its own interests, by their attitudes of tribunes of the people, by the revindication of popular liberties. But in the anonymous reign of the republic, while amalgamating the modes of repression of old pastregimes (taking out of the arsenals of all past regimes the arms of repression), and wielding them pitilessly, the different fractions of the ruling class celebrate an orgy of renegation. With cynical effrontery they deny the professions of their past, trample under foot their “so called” principles, curse the revolutions they have provoked in their name, and curse the name of the republic itself, although only its anonymous reign is wide enough to admit them into a common crusade against the people. Thus this most cruel is at the same time the most odious and revolting form of class rule. Wielding the state power only as an instrument of civil war, it can only hold it by perpetuating civil war. With parliamentary anarchy at its head, crowned by the uninterrupted intrigues of each of the fractions of the “order” party for the restoration of each own pet regime, i n open war against the whole body of society out of its own narrow circle, the party of order rule becomes the most intolerable rule of disorder. Having in its war against the mass of the people broken all its means of resistance and laid it helplessly under the sword of the Executive, the party of order itself and its parliamentary regime are warned off the stage by the sword of the Executive. That parliamentary party of order republic can therefore only be an interreign. Its natural upshot is Imperialism, whatever the number of the Empire.

Under the form of imperialism, the state power with the sword for its scepter, professes to rest upon the peasantry, that large mass of producers apparently outside the class struggle of labour and capital, professes to save the working class by breaking down parliamentarism and therefore the direct subserviency of the state power to the ruling classes, professes to save the ruling classes themselves by subduing the working classes without insulting them, professes, if not public welfare, at least national glory. It is therefore proclaimed as the “saviour of order”. However galling to the political pride of the ruling class and its state parasites, it proves itself to be the really adequate regime of the bourgeois “order” by giving full scope to all the orgies of its industry, turpitudes of its speculation, and all the meretricious splendours of its life.

The state thus seemingly lifted above civil society, becomes at the same time itself the hotbed of all the corruptions of that society. Its own utter rottenness, and the rottenness of the society to be saved of it, was laid bare by the bayonet of Prussia, but so much is this Imperialism the unavoidable political form of “order”, that is, the “order” of bourgeois society, that Prussia herself seemed only to reverse its central seat at Paris in order to transfer it to Berlin. – The Empire is not, like its predecessors, the legitimate monarchy, the constitutional monarchy and the parliamentary republic, one of the political forms of bourgeois society, it is at the same time its most prostitute, its most complete, and its ultimate political form. It is the state power of modern class rule, at least on the European continent.

This long passage contains all the themes and issues concerning the political aspect of the bourgeoisie. Marx thought that the “pure form” of bourgeois political rule, the culmination of its political hegemony, was the bourgeois republic :

The defeat of the June insurgents, to be sure, had now prepared, had leveled the ground on which the bourgeois republic could be founded and built, but it had shown at the same time that in Europe the questions at issue are other than that of ―republic or monarchy. It had revealed that here ―bourgeois republic signifies the unlimited despotism of one class over other classes. It had proved that in countries with an old civilization, with a developed formation of classes, with modern conditions of production, and with an intellectual consciousness in which all traditional ideas have been dissolved by the work of centuries, the republic signifies in general only the political form of revolution of bourgeois society and not its conservative form of life – as, for example, in the United States of North America, where, though classes already exist, they have not yet become fixed, but continually change and interchange their elements in constant flux, where the modern means of production, instead of coinciding with a stagnant surplus population, rather compensate for the relative deficiency of heads and hands, and where, finally, the feverish, youthful movement of material production, which has to make a new world of its own, has neither time nor opportunity left for abolishing the old world of ghosts.

(18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte)

To put a long story short, for Marx the bourgeois republic enabled the modern propertied classes to center their shared class interests as the status quo of the way politics works, so that the inevitable conflicts between and within them, be they social-economic or ideological-partisan (in Marx these two aspects are generally tied), don’t put their overall supremacy at risk – as is the case when uprisings and revolutions break out. Therefore, this political form could enable them to prioritze the rule of their class over that of one privileged faction thereof. Marx says that in France the big landowners (Legitimists, had ruled during the Restoration) on the one hand, the ‘finance aristocracy’ and ‘big industrialists’ (Orleanists, ruled during the July Monarchy – I think…), finally could form a “bourgeois mass” who, in the form of the republic, could rule co-jointly. He therefore talked about the “Party of Order” not as a specific political party, but as the cooalition of the ruling classes, in this case made of both Legitimists and Orleanists, landowners and capitalists, etc… You can see why Marx thought reaching the form of the bourgeois republic represented the political culmination of the rise of the modern capitalist social structure. That certainly doesn’t mean that the bourgeoisie doesn’t settle for a monarchy if it has or want to, in other contexts. Indeed, all these political writings on France tell the story of one regime emerging after another, before falling in its turn.

[I won’t get into more material right now, all the essentials were covered but obviously this could be extended into a whole book since Marx talks about it in most of his published and unpublished, finished and unfinished writings, not to mention the letters]

End Notes & References:

1) Stefano Petrucciani. ‘Le concept de classe dominante dans la théorie politique marxiste’, Actuel Marx, 2016/2 (n°60), p. 12-27.

2) Personally, I prefer using “the capitalist class”, and “the proletariat” on the other hand, because they seem better fitted to define the agents of both sides of the capital relation, i.e., capital and labour. Hence ‘production/industrial workers’ are obviously not the only proletarian category. Capital doesn’t merely comes down to private factory owners, but includes – in a nutshell – all ruling actors who own and control capital, and define the ends of capitalist production (choice of investments and allocation, goals of production, etc…), for the endless reproduction of capital accumulation. That means for example that state capital implies a capitalist faction existing at the top of state and bureaucratic power.

3) This is from John Eatwell, Murray Milgate, Peter Newman (Eds.), Marxian Economics, Palgrave Macmilan UK, 1990, p. 59-62.

4) I have used, for the sake of accuracy, Moseley, F. (Eds.). (2015). Marx’s Economic Manuscript of 1864-1865. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. The title remains the same, but it was Engels who reorganized the book’s structure so ordered the chapters in such a way as to make this one the 23th.

5) To be fully transparent, this was about the last paragraph on page 481. However, Marx is talking about the same thing…

6) Marx also talks about workers’ cooperatives and joint-stock companies, which is also really interesting. For instance, he says: Joint-stock companies → “tendency to separate this labour of superintendence more and more from the possession of capital [490]

7) For this section, I chose not to repeat the well known passages from the Communist Manifesto that mentions similar topics and arguments. I think the material from Capital I is more valuable, because it’s the outcome of Marx’s long-term research project as opposed to a – admittedly brilliant – political pamphlet. Notice that various things from the Communist Manifesto are congruent with the more sophisticated argument in Capital, despite their lack of nuance (in the former). In the Communist Manifesto, Marx said that the bourgeoisie played “a most revolutionary part”. Earlier, in his Introduction to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1844), he offered an interpretation of this revolutionary role: It is not the radical revolution, not the general human emancipation which is a utopian dream for Germany, but rather the partial, the merely political revolution, the revolution which leaves the pillars of the house standing. On what is a partial, a merely political revolution based? On part of civil society emancipating itself and attaining general domination; on a definite class, proceeding from its particular situation; undertaking the general emancipation of society. This class emancipates the whole of society, but only provided the whole of society is in the same situation as this class – e.g., possesses money and education or can acquire them at will.No class of civil society can play this role without arousing a moment of enthusiasm in itself and in the masses, a moment in which it fraternizes and merges with society in general, becomes confused with it and is perceived and acknowledged as its general representative, a moment in which its claims and rights are truly the claims and rights of society itself, a moment in which it is truly the social head and the social heart. Only in the name of the general rights of society can a particular class vindicate for itself general domination. For the storming of this emancipatory position, and hence for the political exploitation of all sections of society in the interests of its own section, revolutionary energy and spiritual self-feeling alone are not sufficient. For the revolution of a nation, and the emancipation of a particular class of civil society to coincide, for one estate to be acknowledged as the estate of the whole society, all the defects of society must conversely be concentrated in another class, a particular estate must be the estate of the general stumbling-block, the incorporation of the general limitation, a particular social sphere must be recognized as the notorious crime of the whole of society, so that liberation from that sphere appears as general self-liberation. For one estate to be par excellence the estate of liberation, another estate must conversely be the obvious estate of oppression. The negative general significance of the French nobility and the French clergy determined the positive general significance of the nearest neighboring and opposed class of the bourgeoisie.

8) And this is the basis of Mau’s thesis, whose title is based on this passage, as you can see.

9) For Marx, it seems, roughly throughout the 14th to 16th centuries, as regards England and France.

10) Because they ‘held land under very different tenures’ than large landed proprietors and ‘were therefore emancipated under very different economic conditions’.