Understanding Contemporary Media Ecology, Disinformation & Propaganda

Some authors who completed meta-analyses (Abu Arqoub et al. 2020, Li and Tang 2012, Zheng et al. 2016, Wasike 2017) have criticized the fact that most of the research on disinformation (and “fake news”) and in media and communication studies is atheoretical. It’s therefore necessary to use some insights of social science (sociology/polsci/etc), critical theory (marxist, feminist, etc) and cultural studies (e.g. Stuart Hall) to examine and decypher the social logic/dynamics characterizing these phenomena.

Having studied a transnational movement of solidarity which relies heavily on digital media (the Milk Tea Alliance) during my MA thesis, I encountered a few useful conceptual frameworks/approaches and theoretical contributions (in a sea of positivist asociological bullshit) for understanding contemporary media and digital technologies in their sociotechnical, cultural and political complexity. The most useful research that I found put the emphasis/focus on concepts/approaches such as media practices, mediation processes, mediatization, hybridity, performance/performativity, relationality and affordances, all of which are summarized and contained in the idea of media ecology (or ecosystem):

A media ecology is the constellation of entities and individuals, organizations and institutions that make up the give-and-take of public information exchange in any particular community (Postman 2000). Stemming from the natural sciences, the metaphor ecology is meant to evoke networks of relationships and association characterized by competitions and synergies and an embedded interconnectedness of any actor to its environment. In this system, individuals work to attain better positions, to learn more, to persuade, to impede the progress of competitors, to build capital, to advance knowledge, to win support/votes/love/friendships, and to otherwise improve their place in the greater uni- verse. Lots of work is being done in this area as scholars seek to understand how these ecologies—considered in this framework to be fluid, organic, living things—fluctuate, expand and contract as new actors are introduced and old ones react. At first those discussing media ecologies such as Neil Postman, Marshall McLuhan and others steeped the conversation in a literal biological understanding of what was happening as people became more and more dependent upon symbols, language, and ubiquitous media in their modes of survival as a species (Havelock 1982; Postman 2000; Ong 1982; Scolari 2012). Later, James Carey (1989) and others draped a more abstract veil over the conceptualization as they sought to understand people’s relationship to the world around them through the rituals and other meaning construction that emerged through media use. Both of these framings assume the ways in which we have adopted media from radio and television to cell phones and the Internet represent an essential and innate inter- relation with the global universe and all of its inhabitants. In other words, everyone is connected through media and communication and through these exchanges, we understand who we are and how to act. (Robinson & Anderson 2020: 989)

In this article I won’t get into an abstract theoretical discussion about the various concepts cited above, privileging a more straightforward sociopolitical analysis of disinformation, propaganda, and some other destructive aspects of digital socialization. This doesn’t address the other side of the sociotechnical dialectic of modern media (i.e. its emancipatory potentials and non-destructive dimensions), nor offers a comprehensive examination of the political economy and informational/algorithmic/etc ecology of modern media. As you’ll see it’s already extremely long and wideranging, so those topics are better left to be discussed another time (or by someone else to be honest). We can define misinformation, disinformation and propaganda as follows:

- Misinformation refers to the overall production and circulation of false or misleading information, regardless of intent. Part of this is unintentional misinformation, which is especially relevant in the age of the Internet/social media/messagings apps.

- Disinformation is a subset of misinformation – the part of it rooted in the deliberate goal/will to deceive or manipulate people.

- Propaganda is, in the words of Guess & Lyons (2020), “any communications that are intended to persuade people to support one political group [note: or viewpoint/project] over another”.

The distinction between unintentional misinformation and disinformation is very blurry and ambivalent, because literally everyone – yes, everyone because as Howard Zinn said, “You can’t be neutral on a moving train” (the train being human society, politics and subjectivity) – is biased towards seeking and sharing information/content/narratives/discourses that fits with their pre-existing cognitive, ideological, intellectual/theoretical/conceptual, and cultural perceptions, beliefs, principles and so on. This doesn’t mean everyone is vicious and seeks to deceive and manipulate others, it’s just that humans aren’t normatively/morally neutral or non-subjective/non-judgmental beings. That means that anyone can share misinformation with absolutely no ill intent but not seeing that something’s off. Recently, during the October 2023 events in Israel and Palestine (Hamas attacks and then genocidal attack on Gaza by Israel), misinformation surged online. And tragically, some footage and content about bombings and atrocities committed by Assad/Russia in Syria were sometimes shared as depicting Israel’s own crimes. Many of the people who shared these things online had no intention to spread disinformation about Assad’s crimes, they were rightly outraged at the (obvious and documented) atrocities committed by Israel.

Here’s an example: this video – which is described as showing Israel’s bombing of Palestinian homes in Gaza – actually uses footage of Assad’s bombing of a residential area in Yabroud, Syria, in 2013.

Where it gets complicated is of course that disinformation actors – from specific groups or people, to anyone in general who wants to antagonize their political/ideological opponents so much that they’re ready to use any hammer of deceit they can find to hit as many nails as possible – are also (almost) always part of moments/waves of misinformation as well. They seek to exploit the authentic concerns, feelings/emotions, intentions of ordinary folks, for their own agendas/gains/interests. And coming back to the Israel/Palestine context, it’s obvious that pro-Israel, pro-Assad and other deceitful actors deliberately targeted people’s grief and outrage at what was going on to reinforce their own agendas by sharing fake, distorted, decontextualized pieces of information/content.

- Shayan Sardarizadeh made multiple threads on this misinformation: day 1 (October 7), day 2, day 3, day 4, day 5, day 6, day 7, day 8, day 9 (Shayan has continued after day 9, but that’s enough lol)

Obviously, disinformation and propaganda are closely related and basically disinfo is part of propaganda. Because the latter includes priming, framing, and agenda-setting more broadly, but not necessarily or exclusively by lying or deception: certain truths can be used for propagandistic purposes just as well as lies or disinfo. And the process of propaganda also relies on simple interpersonal dynamics such as just shouting louder and harassing people more than your opponents, or appealing to people’s pre-existing beliefs, prejudices, biases, and preferences. Common propaganda techniques include rewriting history, using artificial polls/surveys, magnifying/exaggerating and/or oversimplifying certain events (in the past and present), the spectacularization of (alleged or real) mass mobilizations (this is a favorite of regimes like Venezuela’s populist caudillos or Iran’s theocratic fascists), the censorship of and self-censorship in the media, the strategic use of coded and deliberate words/concepts/slogans (“newspeak”), good-old scapegoating, and nationalist warmongering/chauvinism.

The goal of propaganda is to fill the media/public spheres with specific self-serving political themes/ideas/conceptions/messages, to the point of saturation: it becomes harder and harder for the public – or sometimes more precisely, specific groups that are targeted – to avoid the manipulation and disinformation. And propaganda is as just much about what people can’t see – because of this control/censorship/manipulation of information – as what they can: for example, seeing only the dehumanization of certain groups (e.g. reactionary lies about trans people), without any access to/visibility for positive or humanizing stories/information (e.g. stories about trans joy, but also their suffering and oppression).

The notion of “fake news”, in the way it is generally used in mainstream media and politics, is at best a useless concept, and at worst a problematic and disingenuous one instrumentalized for political or ideological ends. But from a more rigorous social science perspective, some scholars like Julien Giry argue that they do represent a tangible phenomenon:

Fake news consist in the deliberate circulation in the public arena, by identified or identifiable social actors, of deliberately false and misleading performative statements for which they assume enunciative, discursive, political or even judicial responsibility.

These statements mobilise affects, symbolic stereotypes, collective prejudices or cognitions specific to their universe of enunciation, and they are knowingly designed to deceive the public with a view to political and/or economic repercussions favourable to their authors and/or unfavourable to their adversaries, opponents or competitors” (Giry 2020, translated)

However, as far as I’m concerned it’s really just part of disinfo/propaganda in a general sense: I’m not really interested in distinguishing/setting apart what Giry is describing here from the broader phenomenon itself. In other words, his defnition here is interesting, but I’d rather think about these social dynamics/interactions as characterizing (at least some forms of) disinfo/propaganda more generally.

I’m focusing here on disinformation and propaganda (and to a lesser extent on unintentional misinformation), which means that I won’t be addressing every aspect of the media, information, and attention/cognitive economies and ecologies of contemporary society. For example, For the most part, I won’t get into misinformation caused by either or both the media’s incompetence/problematic practices and/or (lack of) media/information literacy, i.e. understanding and being able to assess/verify/discuss facts, data, information, and news/events critically/rigorously.

The objectivism/fetishism of modern (western) science – and with it of technology, information and data/numbers – is also another interesting aspect that needs to be discussed when considering media and information ecology. Numbers – for example in the form of polls and surveys – are largely perceived as inherently objective and reliable (more than humans, in fact) because of the cultural hegemony (in the West, at least) of bourgeois positivism. But in reality any statistic, any survey, any chart should be examined rigorously and critically, because from both an epistemological (what can we know and how can we actually make sure to grasp reality/truth) and methodological (how to work to maintain as high a level of empirical and theoretical rigor as possible) standpoint, all kinds of bias, mistakes, deceptions, or misleading interpretations can be introduced in the production, collection/recording/measuring, construction, and/or presentation of data/information. For instance, data visualization specialist/educator Alberto Cairo wrote a useful book about understanding charts and how they can deceive, where he said:

Charts may lie in multiple ways: by displaying the wrong data, by including an inappropriate amount of data, by being badly designed—or, even if they are professionally done, they end up lying to us because we read too much into them or see in them what we want to believe. At the same time, charts—good and bad—are everywhere, and they can be very persuasive. This combination of factors may lead to a perfect storm of misinformation and disinformation. We all need to turn into attentive and informed chart readers.

In addition, the same data can often be interpreted in multiple ways, and contratry to the positivist illusion of full objectivity, data doesn’t describe reality unequivocally. I would say this is especially true in the context of studying human societies (social relations, interactions, history, culture, politics, you name it!), which unlike chemical reactions or environmental phenomena, cannot be isolated and studied in a lab or measured in a very precise and reliable way. These are all very important epistemological and methodological considerations in the realm of social science (but also others sciences, needless to say), but obviously I’m not gonna expand this discussion here. I’ll include some resources and readings on these other topics at the end, let’s move on now.

Although the existing research on this remains limited/underdeveloped, there’s no scholarly consensus that Internet and social media per se have a direct/straightforward/unequivocal/automatic impact on people’s views/beliefs and behaviors, e.g. specifically on the increased spreading of disinfo. On the contrary, individuals aren’t as malleable and passive as is often assumed, especially in mainstream discourse (i.e. media, politics and academia), nor is it possible to understand all this while ignoring the social totality that forms the structure(s) and everyday environment(s) humans live in. The socio-historical context – and especially social relations/systems of oppression and the hegemonic cultures/ideologies/identities/institutions/norms that both reproduce and are produced by them – is obviously the source of major determinations but some overly individualistic/psychological interpretations/assumptions are quite widespread, and largely offer depoliticized, ahistorical, asociological analyses/explanations.

Generally speaking, individuals’ own social, economic, cultural, biographical background/socializations on the one hand, and in particular their preexisting political/ideological preferences/dispositions on the other, generally have a greater role in determining their behaviors than the specific technology they’re using (not that it’s totally irrelevant, but it certainly doesn’t precede individuals’ socializations in the funnel of determinations). Hence, the use of the Internet and social media does potentially expose/confront people to all kinds of misinformation or conspiracy theories, but the research doesn’t show (important note: these findings come from aggregate data, so it’s only an overall trend and doesn’t mean specific patterns can’t be observed!) that using these technologies/platforms in and of itself leads people to increasingly share or agree with ‘fake news’ and political propaganda, if those individuals aren’t predisposed to seek out or be attracted to such ideas. It might sound a bit obvious and redundant (e.g. people who are predisposed to look for and/or share conspiracist stuff are… the most likely to do so), but what it does show is that the medium/tools, specifically Internet, news and social media, have a limited determining role in causing behaviors or certain beliefs.

Let’s be clear: it doesn’t mean disinfo/propaganda aren’t a huge problem online – otherwise I wouldn’t even have written all this! -, rather it’s about understanding what’s really going on without relying on false positivist assumptions, which are still widespread in bourgeois scientific research (here more specifically polsci, communication and media studies, disinformation studies, and so-called “counter-extremism” research). So the bottom line isn’t that Internet/social media don’t matter or that they don’t have a very important role: rather they must be seen as mediations of people/groups’ behaviors/actions, which are usually (but not always) determined by offline socializations and individuals’ own politicizations (their worldview, beliefs, political leanings, prejudices, etc…. which again are all strongly tied to socialization/social background) as much or more than online ones. And in my view it’s likely that traditional media have a similar nonlinear relation to/impact on individual behaviors: they can be very influential, but only in the general context of people’s socializations and social relations.

The reactionary conception – typical of elitist and conservative circles (i.e. within the social spheres of politics, media/journalism/pundits, think thanks and academia) – where the dumb “masses” are defined as a dangerous irrational swarm, is merely the predictable reaction from members of dominant social groups who can’t help but have moralizing/condescending contempt over any form of lower-class/proletarian subjectivity, agency, and politicizations. It’s derived from an aristocratic worldview and anxiety that conflates all groups and strata of the social hierachy that lie beneath them: the proletarians, the wageless, the displaced/marginalized, the middle layers/strata, the rural poor and the petit bourgeois, are all homogeneized into a n unruly “rabble” that doesn’t respond to “reason” and threatens the social order.

Hence, the notion of the masses as a dangerous, irrational (non-)subject which regularly falls into so-called “mob mentality” or “herd instinct” (Wilfred Trotter) has a long history in both liberal (Walter Lippmann, Edward Bernays) and conservative/reactionary (Gustave Le Bon) thought/conceptions. And it’s noteworthy that Bernays – a pioneer in the realm of “public relations” and political/economic propaganda (though sometimes people overstate how groundbreaking he was: which is funny because that’s precisely a ‘public relations’ campaign he himself pursued to build his reputation as “America’s No. 1 Publicist”) – himself held the same view, in a very transparent and explicit way. He literally saw the “masses” as what conspiracists like Alex Jones would call “sheep” or “sheeple”: completely blind and unthinking non-agents who are inevitably manipulated by an elite minority.

Bernays unironically believed that good propagandists should compete with evil ones: “the only way to stop a bad guy with a propaganda apparatus, is a good guy with a propaganda apparatus.” Reminder that this guy not only pioneered the field of economic propaganda (“advertising”/etc), but worked for the likes of General Electric, Procter & Gamble, and the infamous United Fruit Company for which he ran the propaganda campaign to legitimize in the eyes of the US public the CIA-orchestrated coup in Guatemala to overthrow Jacobo Árbenz, which among other things was a precursor to the “Maya genocide” led by Efrain Ríos Montt. Bernays inspired a multi-disciplinary field of research called “Engineering of Consent” (which was the title of he used in his 1947 essay and in a 1955 book he edited) which goes on to this day.

The point here isn’t to deny that manipulating so-called “public opinion” (an inherently bourgeois and nonsensical notion btw) or the public’s desire for and willingness to pay for certain commodities, is inefficient. PR and advertising wouldn’t be the gargantuan industries that they are today (as I’ll describe later below) if political and economic elites saw at some point that it didn’t help them get richer and more powerful. But the positivist and reifying assumptions of bourgeois academia and media largely lack the sociopolitical perspective and critical/dialectical method to understand what’s going on. Ultimately, individuals’ and society’s politicizations can only be analysed properly by focusing on the concrete sociopolitical processes at play. That means identifying the actual forces/actors, networks and interactions/relations characterizing disinformation, propaganda, and more generally modern media, and its various sociotechnical mediations. Emmanuel Taïeb’s call to “bring politics back in” (repolitiser, literally “repoliticize”) – written in the context of the research on conspiracism – is relevant when analyzing disinformation/propaganda/etc:

It seems to us essential to ‘re-politicise’ conspiracist discourse analytically, as an act of language used by particular actors pursuing political objectives. Rather than thinking of conspiracism as an outgrowth of traditional supertitious/mystic captivation/beliefs, rather than defining it in psychological terms or seeing it as a survival of the irrational in our modern world, we need to study how it is used to politicise a certain number of issues. By ‘politicising’, we mean publicly re-characterising/reframing factual information about a given event, turning it into an issue of disputed significance and challenge/question the public and political actors about it. We can see that conspiracy rhetoric is used as a resource and as a political stunt by politicisation “entrepreneurs”. For them, using conspiracy rhetoric is an effective way of participating in the official/legible/bourgeois political game. This is because conspiratorial discourse has a performative aim: by spreading the conspiracy thesis, it aims to make it triumph in people’s minds, influence the political agenda, impose the alternative knowledge on which it is based, and make political reality conform to this vision of the world. (Taïeb 2010: 280, translated and slightly modified)

Conspiracism is part of the wideranging spectrum of potential politicizations, which includes phenomena as diverse as social critique, political artwork, mutual aid, riots, looting, infrapolitics, bourgeois elections, terrorism, public demonstrations, workers’ strikes, cultural discourses and industries, official state-enforced ceremonies/rituals, and so on… It’s never completely (pre)determined beforehand which mode of politicization (and action, but also sometimes inaction) – quietist/hidden or public/visible, disruptive/contentious or not, violent or non-violent, state-oriented or community-oriented, explicitly or implicitly political, ideology-driven or otherwise, etc. – an individual or group will turn to/adopt in some kind of situation/setting. The definition of politicization is therefore inherently plural, and implies detailed attention to/analysis of concrete processes wherever and whenever they arise. Moroccan political scientist Mounia Bennani-Chraïbi calls these diverse processes “politisations différentielles” (literally “differential/differentiated politicizations”), which she defines as:

the various sites of interaction between the governed and the plural agencies of governmentality, involving various forms of participation, of individual and collective mediation, whether organised or informal, within or outside the law, with particularist or universalist aims, around access to goods, rights, justice and recognition (Bennani-Chraïbi 2011: 56, translated)

Regarding disinformation and propaganda in our time, here are some noteworthy findings of the existing research so far. As I already said, to a large extent individuals aren’t malleable and passive: ideological and political predispositions play a huge role in determining who engages in disinformation (i.e. deliberately spreading false or misleading information/claims/etc), rather than merely an inability to distinguish between “true” and “false” information, or even believing in the “fake news” they share. That might seem counterintuitive from a rationalist perspective (i.e. wherein political beliefs and attitudes are presumed to be caused by individuals consciously developing a politicized and coherent argument based on intellectual reasoning), but part of the research found that “political/partisan polarization” (meaning an antagonistic opposition and even hatred of one’s political/ideological opponents/”enemies”) is the most important factor in sharing “fake news” online. This means that individuals don’t even necessarily have to convince themselves of a story/piece of info’s truthfulness – by missing or denying its false claims/data/arguments – in order to share it: it’s often simply about accusing/targeting their political/ideological opponents. Of course, that doesn’t mean cognitive bias or the inability to verify/process information doesn’t play a part; it’s always been an issue, but the contemporary information ecosystem center by the Internet and social media, is particularly messy and corrosive.

However, what it is clear from the above is that neither cognitive/literacy issues, nor the mere use of social media, are the primary drivers of why disinformation and propaganda exist and work: what they do is influence, reinforce, politicize, shape individuals’ pre-existing political/ideological leanings/beliefs/identifications/etc, as well as possibly to some extent shaping the concrete (and differentiated) translation from specific beliefs to specific modes of actions or attitudes.

Moreover, social structures and hierarchies obviously form the background against which individuals’ behaviors and beliefs must be analyzed, because their socializations (interactions and all social norms/relations/etc in the family, at school, at work, with and against authorities e.g. police/social services/politicians, at religious institutions e.g. local church or mosque, and so on) are the most determining factor(s) concerning their relation to information, disinformation, epistemic authorities, various forms of propaganda, and the media. The set of contributions/discussions I cited earlier – Sarah Nguyễn et al. (2022), Rachel Kuo and Alice Marwick (2021), and Miriyam Aouragh and Paula Chakravartty (2016); and this exchange between J. Khadijah Abdurahman and André Brock, Jr.; to which I’d also add Aman Abhishek (2021)’s article on the political economy of propaganda and misinformation in the Global South – call for greater attention to how social differentiation, social hierarchies/institutional power, transnational news networks and informational infrastructures, and legacies of imperialism/militarism and ongoing geopolitical tensions, influence/shape information/disinformation beyond eurocentric and white subjects/communities which have been the main object of research (i.e. focusing almost exclusively on “angry white males”). As a random European anarchist I’m not gonna pretend I can contribute to this myself, and I’m pretty sure there are limitations to my whole analysis/framework because of my own background/epistemic-intellectual context. That’s why I wanted to mention these contributions, because I resonate with their critiques/objectives and they’re important for expanding and improving the study of these topics at a global level.

Let me clarify what I mean when I say ‘pre-existing political leanings/beliefs’ on the one hand, and ‘social structures/hierarchies’, on the other, determine individuals’ tendency to engage (or not engage) in disinfo and propaganda. I don’t have a single group in mind, nor a specific type of disinformation/propaganda, because the fact of the matter is that similarly to conspiracism, they apply across social classes, across so-called ethnicities, across genders, and so on. Importantly, they often differ in their form/content/etc from one group (say, white cis males in the US) to another (non-white and Indigenous women and other gender minorities, in the US), but the point is that it’s not specific to one single social group/category. For instance, regarding conspiracism, it’s clear that it’s not merely the supposedly ignorant lower classes that engage in it: the petite bourgeoisie, middle classes and elites are just as likely to do so, though as you probably guessed it’s usually in different shape/way… Lastly, some specific contextual factors can increase the likelihood/effectiveness of disinfo/propaganda/etc, such as decreased trust in official epistemic authorities, contexts of intensified/high uncertainty or tragedy, or social groups perceiving themselves to be excluded from political power.

Chomsky and Hermann’s model fails to offer a proper sociological explanation of disinfo/propaganda, because it is based on a reductionist – economicist and conspiratorial – theoretical framework. Despite its huge popularity among sections of the Western left, this perspective pales in comparison to Stuart Hall’s contribution a decade earlier, which is now usually referred to as the encoding/decoding model of communication. In this interesting paper, Hall emphasizes four important and interlocked dimensions of how information/communication works, which Chomsky and Hermann almost completely fail to take into account by reducing people to passive acritical automatons:

- The capitalist conditions of production of media messages

- The stereotypical/biased/ideological content of these messages

- The relative autonomy of the professional norms/practices which characterize their production (e.g. what Bourdieu would call the competitive or symbolic properties of the ‘journalistic’ field)

- The audiences’ variable (but real) ability to critically filter media messages/information

Moreover, the relation between dominant (economic, political…) forces and the media’s “encoders” (i.e. those that produce messages for the public) is poorly theorized by Chomsky and co, whereas Hall acknowledges the dynamic and conflictual tension that lies at its core:

the broadcasting [note: media] professionals are able both to operate with ‘relatively autonomous’ codes of their own and to act in such a way as to reproduce (not without contradiction) the hegemonic signification of events (…) the professionnal codes serve to reproduce hegemonic definitions specifically by not overtly biasing their operations in a domination direction: ideological reproduction therefore takes place here inadvertently, unconsciously, ‘behind men’s backs’. Of course, conflicts, contradictions and even misunderstandings regularly arise between the dominant and the professional significations and their signifying agencies

Stuart Hall (1973) Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse, p. 516.

I recommend reading more (see here and the paper itself) about this theoretical model, which is of course not a definitive or ultimate theory of media/propaganda, but a very good starting point for sociological and critical analysis of that aspect/dimension of modern society. Recently a volume with Stuart Hall’s writings on media was published, including but also beyond the 1973 essay. Another useful contribution from Hall and the CCCS is the concept of “primary definers”, here explained by Mari Cohen:

Hall and his coauthors argued that the tight deadlines and culture of “objectivity” found in the newsroom led reporters to frequently turn to a particular set of easy-to-reach established voices—whom Hall calls “primary definers”—to serve as experts, resulting, in Hall’s words, in a “systematically structured over-accessing to the media of those in powerful and privileged institutional positions.” It’s easy to see how this operates in contemporary crime coverage, where law enforcement accounts tend to serve as the backbone of news reporting (…) Hall argues that while journalists often give “counter definers” who dissent from institutional interpretations a voice in their stories, such actors are forced to respond within the framework already laid out by the primary definers, and therefore, in a sense, have already lost the battle.

There are other interesting theoretical/scientific approaches – such as the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA) developed by Ruth Wodak, who has done important research on racist and far right discourse/propaganda – but the point is that the very reductionist and narrow-minded Chomskeyan framework was already obsolete/inadequate when it came out back then, and so it’s just lazy that so many people keep hanging on to it uncritically. In other words, analyzing propaganda and discourse/media/ideology/cultural production is important, but we can do a lot better than this kind of pseudo-critical approach; I’ve tried selecting some useful conceptual/analytical tools in the above and throughout the next sections below.

Based on the above-mentioned considerations and arguments, analysing modern propaganda and disinfo first and foremost requires a critical examination of the various particular actors that use and practice it as a method of politicization, manipulation and/or domination/violence. The prevailing matrix of social relations in capitalist and postcolonial modernity, obviously produces and is reproduced (in part) through hegemonic ideology, essentialisms, prejudices, dehumanizations, and myths. Propaganda and the media certainly play a role in these cultural/ideological socializations, alongside institutions like the family, schools, and the workplace. Moreover, it’s important to analyze the specific forces and actors that intentionally produce and use disinformation and propaganda, regardless (but needless to say, not autonomously from) these “structural” forms of politicization and ideological production/socialization.

In the end, it’s crucial to conceptualize and analyze both dimensions of modern propaganda/media, since they overlap, coexist and determine each other reciprocally: ideology/propaganda as processes of social reproduction on the one hand, and of politicization, on the other. Defining it as social reproduction matters as a way to always connect it to the social totality, whereas studying it in terms of politicization is necessary in order to understand the specific political projects, forces, worldviews, strategies of contemporary society.

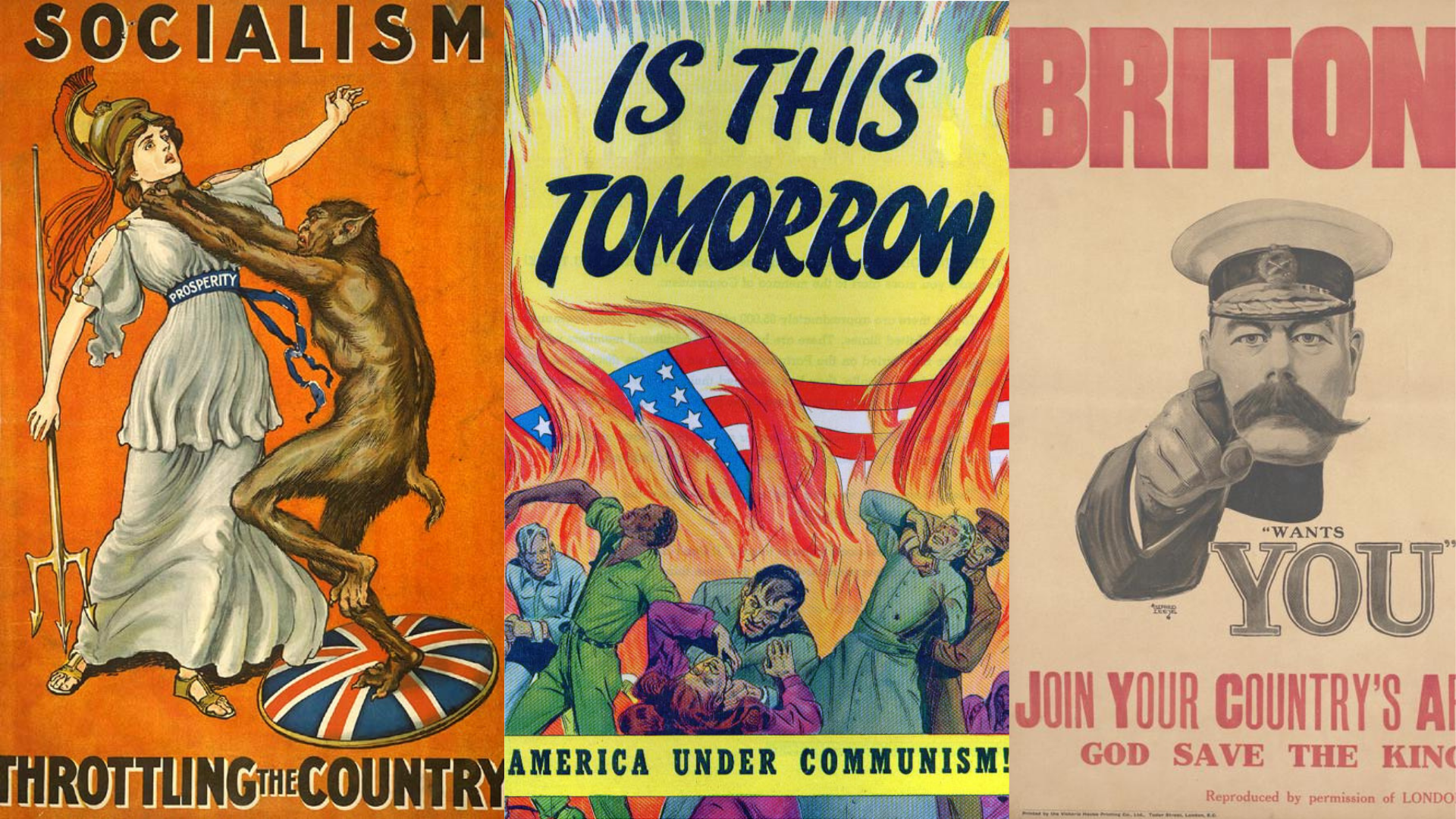

Featured propaganda poster (sources):

“Socialism Throttling the Country” was a poster commissioned by the Conservative Party in Britain in 1909, depicting the “beast” of socialism endangering the plight of British prosperity. [Source]

Is This Tomorrow: America Under Communism! was an anti-Communist, Red Scare propaganda comic book published by the Catholic Catechetical Guild Educational Society of St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1947. [Source]

Britons (Lord Kitchener) Wants You, by Alfred Leete, Great Britain, 1914. WWI army recruitment poster. [Source]