One of the most disgusting forms of propaganda is the ideological/cultural glorification and legitimization/rationalization of policing, often referred to as copaganda. This is something that E. P. Thompson already noted more than fourty years ago (and doubtless, many poor and oppressed people decades before that):

Without using the term copaganda, historian E.P. Thompson in the late 1970s drew attention to this phenomenon’s British manifestations. He observed a tendency towards the ‘populist celebration of the servants of the state’ exemplified on British television by the “homely neighbour and universal uncle, Dixon of Dock Green – the precursor to more truthfully-observed heroes of Z-Cars.” He emphasised the impact of the Second World War and the early Cold War on views of the police held by the public and even the Labour Party: “The bureaucratic statism towards which Labour politicians increasingly drifted carried with it a rhetoric in which the state in all its aspects was seen as a public good… [T]he dividing line between welfare state and police state became obscure.” [source: wiki]

Although a worldwide phenomenon, it is perhaps most glaring in the United States of AmeriKKKa, or at least this is where one can find some of the most detailed and useful analysis. Indeed while I’ve probably missed some (re)sources because of language barriers (I mainly rely on French and English), it’s frustratingly difficult to find any work/analysis/material that isn’t from and/or about the USA or Canada (or the UK, to a lesser extent). For instance in France there’s been some great work on the history of (French) policing and police brutality, but most things you can find on both police abolition and copaganda are translations of North American texts or discussions on the recent/ongoing movements and debates there (not that it’s a bad thing, but there’s a lack of endogenous stuff that would offer contextualised insights/perspectives). Hopefully I’ll eventually find some more anarchist and radical (or even academic) literature/resources from non-US/Canadian contexts/perspectives, and I’ll talk about them here and provide links when I do. Usually the history of the police, of its brutality and racism/sexism/etc, as well as resistance against it, are more or less satisfyingly addressed/examined in each context/region and language; but not so much concerning copaganda as such.

So please forgive me for focusing primarily on the North AmeriKKKan context, and relying on critical work/research done by activists and journalists there. The police is horrible and racist/reactionary/authoritarian everywhere across the world, and so is the copaganda, but there’s no denying how extreme they both are in the U.S. of AmeriKKKa compared to other wealthy Western countries. Among many other commentators in the past 20-30 years, Alec Karakatsanis, a civil rights lawyer and expert on the U.S. penal/(in)justice system, emphasized the unprecedented scale of incarceration/detention/punishment that basically makes it a carceral society/state (comparable only to contexts such as the era of High Stalinism in the Soviet Union or South Africa at the height of apartheid):

I think the most important thing that is unstated in almost all media coverage of the criminal punishment bureaucracy—and, more broadly, about issues of public safety—is that the U.S. is currently caging human beings at a rate that is unprecedented in its own history and in the recorded history of the modern world. We’re caging people at five times the rate that we did when Nixon was president. We’re caging people at a rate of five or 10 times what other comparably wealthy countries do right now. Those countries, by the way, have significantly lower levels of violence.

So what we know from our own history and from studying other societies all over the world is that if our giant bureaucracy—cops, prosecutors, judges, probation and parole officers, prison guards, prisons, surveillance technology, companies profiting at every stage of that process—made us safe, we would have the safest society in the history of the world. But those things don’t make us safe.

So there’s this core denial in almost all news coverage of just what an outlier we are in terms of the sheer scope of the project that we’ve undertaken to take people away from their homes and schools and churches and jobs and communities to put them into this government run system of cages, concrete, and metal. And that is an incredible omission.

With that in mind, I don’t see why many of the insights from the North AmeriKKKan context couldn’t be useful in other regions, obviously always with the added relevant contextualisations and historicizations… The police has the same social functions of brutally enforcing and reproducing the capitalist, racist, patriarchal, authoritarian system(s) of modern society. Modern states, whether dictatorships or democracies or something in between, all rely on this “punishment bureaucracy” as Karakatsanis calls it, and more broadly on the brutal inhuman state-border-carceral-policing regime. But I’d definitely be interested to learn more about non-Western regions, i.e. the world outside of Western Europe, North America and Australia/NZ, more precisely about how copaganda works there (e.g. I know that Bollywood produces a lot of Indian copaganda).

Andrea Ritchie, who co-authored No More Police: A Case for Abolition with Mariame Kaba (the book includes a detailed analysis of copaganda), described the general problem of uncritical deference to law enforcement and how it shapes people’s understandings/visions of current realities as well as liberatory horizons:

There’s so much deference to police around everything to do with public safety. What they say is taken as gospel without question, without requiring proof of concept, without requiring any kind of accountability for when what they’re saying actually doesn’t line up with the facts or people’s experiences. (…) We take a little bit of a deeper dive with the help of people like Rachel Herzing, David Correia, Tyler Wall, into how deeply into our language cops speak and copaganda permeates and how that shapes our imagination about what policing is, what it’s doing, what it’s not doing, and the necessity of it.

Indeed, Karakatsanis defines copaganda as “creating a gap between what police actually do and what people think they do”, obviously promoting a positive image of policing that depicts cops as heroic, highly competent and trustworthy public servants, as well as as down-to-earth, relatable members of the community. Meanwhile, the recurrent abuses, localized tyranny and surveillance, racism, corruption, incompetence, mafioso/criminal behaviors (including theft, placing or staging false evidence, harassment and intimidation, torture, blackmail, etc) are supposed to be swept under the rug. Not only are so-called “bad apples” supposed to be a minority, but they’re usually not even recognized as responsible or held accountable for their acts. Copaganda seeks to reproduce and reinforce multiple crucial facets/pillars of the prevailing social order:

a) Ordinary people’s submission to state authority/law enforcement, and thereby the legitimization of the police’s discretionary power (cops having absolute authority to question, stop, search, arrest, beat, etc anyone they’re suspecting)

b) Their acceptance of social hierarchy, and from a cultural/ideological/normative standpoint, anti-egalitarianism:

As British anarchist Colin Ward puts it, “hierarchical systems do not solely rely on fear and brute force to reproduce themselves: it is “far more because [the oppressed] subscribe to the same values as their governors. Rulers and ruled alike believe in the principle of authority, of hierarchy, of power” [Anarchy in Action].

Bakunin defined the “principle of authority” in Marxism, Freedom and the State as follows: “the eminently theological, metaphysical and political idea that the masses, always incapable of governing themselves, must submit at all times to the benevolent yoke of a wisdom and a justice, which in one way or another, is imposed from above”

c) The nationalist myth that in a given country there’s an “us” aka a shared national collectivity with the same “general interest”, rather than mutually incompatible social interests/groups, rooted in relations/systems of domination

d) Dehumanizing depictions of and stereotypes/myths about oppressed groups

(e.g. racialized immigrants and minorities, trans and gender-nonconforming persons, Travellers and Roma people in Europe, neurodivergent people and people with mental health and/or drug/addiction-related struggles, the homeless and the unemployed, occupied/colonized populations)

Here are the three fundamental functions of news/media-based copaganda according to Alec Karakatsanis:

(1) Copaganda narrows our understanding of safety.

Police want us to focus on crimes committed by the poorest, most vulnerable people in our society and not on bigger threats to our safety caused by people with power. For example, wage theft by employers dwarfs all other property crime combined — from burglaries, to retail theft, to robberies — costing an estimated $50 billion every year. Tax evasion steals about $1 trillion each year. That’s over 60 times all the wealth lost in all FBI reported property crime combined in the entire U.S. There are hundreds of thousands of Clean Water Act violations each year, causing cancer, kidney failure, rotting teeth, and damage to the nervous system. Over 100,000 people in the United States die every year from air pollution, five times the number of all homicides.

These are the crimes that are committed by wealthy people, people with power… And then I think there’s an even more basic point, which is that people who have power and influence in our society get to define what a crime is… You can make it a crime to have an abortion. You can make it a crime to have an abortion pill sent to you in the mail… The idea of violent crime is very different from the idea of harm. So, those other types of harm in our society, whether it’s sexual harassment at work or racial discrimination in home lending, [are often not actually] criminalized by the law. [this paragraph is copied from this interview, I thought it fitted perfectly in Alec’s orginal text]

But through the stories cops feed reporters, the public is encouraged to measure a city’s “safety” by whether it saw an annual increase or decrease of three homicides or fourteen robberies — rather than by how many people died from lack of access to health care, how many children suffered lead poisoning, how many families were rendered homeless by illegal eviction or foreclosure, how many people couldn’t pay utility bills because of fraudulent overdraft fees, or how many thousands of illegal assaults police committed.

[more relevant context, based on Alec’s interview with Teen Vogue, Wendy Sawyer and Peter Wagner’s exhaustive report on the U.S. prison system which is linked in the article (see also this 2023 version and the amazing website of the Prison Policy Initiative), and this op-ed by Olayemi Olurin]

1 out of 5 incarcerated ppl in the world are incarcerated in the U.S., for a total of nearly 2 million people and the highest incarceration rate in the world

Most incarcerated ppl are poor and the poorest are women and people of color. Poverty is both a predictor and outcome of incarceration, and at each step in the criminal injustice system poor people are overwhelmingly vulnerable, e.g. the high price of money bail makes poor people more likely to face the harms of pretrial detention; most people – over 400,000 according to the PPI – are not convicted of any crime but locked up in jail awaiting trial

Black people are dramatically overrepresented: they make up around 40% of the incarcerated population while representing only 13% of U.S. residents. They also receive the harshest sentences, including death sentences. “Nearly 60% of incarcerated people are Black or Latino, per PPI’s most recent numbers.”

Most people involved in the U.S. justice system – whether incarcerated or not – are not accused of serious crimes but charged with misdemeanors, low-level and non-violent offenses, including non-criminal violations (probation or parole violations and “holds”). According to the Vera Institute of Justice this amounts to more than 80% of arrests nationwide.

Most people charged with crimes in the U.S. are too poor to afford a lawyer

“Per the Fines and Fees Justice Center, incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people owe at least $27.6 billion in fines and fees nationwide.”

“Incarcerated people, in public and private prisons, produce over $11 billion in goods for almost no income. A 2022 ACLU report found that, on average, most states pay incarcerated people between 13 and 52 cents an hour — of which the government claims as much as 80% — and seven states skip the pretense altogether and pay absolutely nothing for most jobs. Often, incarcerated people can’t afford the basic necessities for which they are charged, their families spend over $2.9 billion in commissaries each year, in addition to another $14.8 billion in costs associated with moving, eviction, and homelessness brought on by these cases.”

Private companies actually aren’t the source of most prison jobs: in the same way that private prisons are only a tiny part of the carceral system, the mass exploitation of prisoners is done by the state, i.e. publicly-owned prisons themselves. This is mainly to keep the carceral system going for the least cost possible: “more than 80% of incarcerated laborers do general prison maintenance, including cleaning, cooking, repair work, laundry and other essential services” [Dani Anguiano, based on ACLU’s research]

“A 2020 report from the American Action Forum found that this country spends an estimated $300 billion on policing and prisons yearly, a figure that has continued to increase despite record drops in crime.”

“In America, police arrest someone every three seconds, according to the Vera Institute of Justice. A 2020 review from University of Utah professor Shima Baughman, however, found that police solve just 2% of all major crimes.”

(2) The second function of copaganda is to manufacture crises around these narrow categories of crime.

For example, if you watch the news, you’ve probably been bombarded with stories about the rise of retail theft. Yet the actual data shows there has been no significant increase. Instead, corporate retailers, police, and PR firms fabricated talking points and fed them to the media. The same is true of what the FBI categorizes as “violent crime.” All told, major “index crimes” tracked by the FBI are at nearly forty-year lows, despite constant media attention paid to “crime surges” and “crime waves.”

(3) The third and most pernicious function of copaganda is to manipulate our understanding of what solutions actually work to make us safer.

A primary goal of copaganda is to convince the public to spend even more money on police and prisons. Although such a view is like climate science denial, the core goal of copaganda is to link safety and crime to things that police, prosecutors, and prisons do.

If police and prisons made us safe, we would have the safest society in world history — but the opposite is true. There is no link between more cops and decreased crime, even of the type that the police report. Instead, addressing the root causes of interpersonal harm like safe housing, health care, treatment, nutrition, pollution, and early-childhood education is the most effective way to enhance public safety. And addressing root causes of violence also prevents the other harms that flow from inequality, including millions of avoidable deaths.

Powerful actors in policing and media thus define crime, manufacture crime waves, and then respond to them in ways that increase inequality and consolidate social control, even as they do little to actually stop crime. Copaganda not only diverts people from existential threats like imminent ecological collapse and rising fascism, but also boosts surveillance and repression that is used against social movements trying to solve those problems by creating more sustainable and equal social arrangements.

Copaganda takes two general forms, based on the type of media it’s produced in/by/as: it’s about shaping perceptions about policing, crime and so on, through news and social media depictions/framings/narratives on the one hand, and through the cultural/fictional depictions, on the other hand. Starting with the former news-based copaganda, the first aspect is simply the symbiotic relationship between the press/news media and the police. In its most blatant form, actors in news media and on social media simply act as the police’s stenographer, repeating their claims, narratives, and language uncritically and without verification or contextualization.

Among a slew of other corrupt, deceptive and malicious practices when collecting or handling evidence, dealing with suspects (and victims) and so on, the police are notorious for lying all the time, yet quite often news media casually repeat their lies. This often happens in the context of crackdowns against activists, protesters or rioters (especially when they are specifically opposing police violence, e.g. the Baltimore uprising in 2015), where cops will use bogus threats to preemptively justify their repressive brutality and abuses and criminalize protesters/activists. This happened during the riots against police brutality in Cardiff on May 23 2023, where the Guardian reprinted the police’s lies verbatim:

The hosts of Citations Needed broke down the key elements of how local “crime” reporting generally constitutes this kind of shameless police stenography:

There are three elements of local crime reporting that we think are in urgent need of dissection and reconsideration and they all more or less follow this formula. The first is the media treating the police as the primary, if not only, source of information for a story effectively acting as press agents for the police, letting them drive the narrative and define what crime itself really is or how we view crime as such.

The second element is the routine plastering of mug shots online, effectively ruining people’s, mostly African American and Latino, lives all on the say so of police on speculation and long before anything actually goes to trial.

The third trope in this genre is the total omission of any type of crime other than street crime, which is broadly viewed as property theft, muggings, burglaries, murder. On the other hand, other transgressions traditionally ignored by police, such as wage theft, so-called white collar crime and even things like campus sexual assault are largely not seen as local crime stories.

The specific language chosen to talk about crime/news stories and law enforcement itself contributes to copaganda in a major way. David Correia and Tyler Wall wrote Police: A Field Guide where they decypher the “indirect and taken-for granted language of policing” which everyone’s forced/supposed to use when talking about law enforcement, despite the fact that it is “the language of police legitimation through the art of euphemism”:

State sexual assault becomes “body-cavity search,” and ruthless beatings become “plain compliance.” Like any other field guide, it reveals a world that is hidden in plain view. In entries like “Police dog,” “Stop and frisk,” “Rough ride,” and scores more.

A notorious aspect of this sordid “art of euphemism” is the falsely neutral use of the passive voice as a way to distort the truth and depoliticize the police’s guilt/agency in committing violence or acting in other problematic ways (that for example lead to deaths or serious consequences that were preventable/unnecessary/unwarranted). Critics call this the “(past) exonerative tense”, a way to acknowledge events/controversies/wrongdoing without taking any responsibility, indeed absolving those who did something wrong and thus implicitly blaming the victim, The most infamous example is the widespread tendency within mainstream media to use the qualifiers “officer-involved” or “police-involved” to describe incidents of police violence (often actual shootings). From Emerson Malone’s write up:

A 2022 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research looked at how “obfuscatory language” used in TV news broadcasts about police killings between 2013 and 2019 affected viewers’ understanding of the story and their perceptions of police. They considered these specific language structures: passive voice, which backgrounds the causal agent (e.g., a civilian was killed vs. an officer killed a civilian), removing the causal agent from a sentence altogether (a civilian was killed after a police chase vs. a civilian was killed by an officer), nominalization, which turns what would typically be an adjective or verb into a noun and makes the causal agent’s actions more ambiguous (an officer-involved shooting vs. an officer killed a civilian), and the use of intransitive verbs, which, unlike transitive verbs, do not have a causal agent behind them (to die vs. to kill or to shoot), further muddying who’s accountable.

Participants in the 2022 study, the researchers wrote, were “less likely to hold a police officer morally responsible for a killing and to demand penalties after reading a story that uses obfuscatory language.” This type of obscuring language is especially common in a news story’s lede, “which is most salient to viewers.” The researchers conclude, “Narrative structures employed by media outlets, which often mirror those used in press releases and tweets by police departments and unions, impact the way that the public understands harms from policing more generally, as well as support for police accountability and reform.”

Following George Floyd’s murder, the headline on the Minneapolis Police Department’s initial statement was rote and reductive: “Man Dies After Medical Incident During Police Interaction” — “an accurate assessment in the sense that every death is in some way a medical incident,” Philip Bump wrote for the Washington Post a year later. As the Floyd story broke, many people criticized news outlets’ framing that the police officer “knelt” on his neck, which characterizes the action as passive and doesn’t adequately underline the violence of the moment.

And as coverage of the botched police response to the Uvalde school shooting showed, there’s a vast difference between a headline that says “Police delayed breaching the classroom because…” and one that says “Police said they delayed breaking into the classroom because…” A minor shift in phrasing separates (a) what’s uncritically parroting the police’s word from (b) what’s technically more accurate.

In the context of the white supremacist U.S. of KKKay, as Devorah Blachor wrote, this reliance on the past exonerative tense “transforms acts of police brutality against Black people into neutral events in which Black people have been accidentally harmed or killed as part of a vague incident where police were present-ish.” It’s actually a poignant example of what George Orwell meant by “Newspeak” in 1984:

The purpose of Newspeak was not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view and mental habits proper to the devotees of Ingsoc, but to make all other modes of thought impossible. It was intended that when Newspeak had been adopted once and for all and Oldspeak forgotten, a heretical thought — that is, a thought diverging from the principles of Ingsoc — should be literally unthinkable, at least so far as thought is dependent on words. Its vocabulary was so constructed as to give exact and often very subtle expression to every meaning that a Party member could properly wish to express, while excluding all other meanings and also the possibility of arriving at them by indirect methods. This was done partly by the invention of new words, but chiefly by eliminating undesirable words and by stripping such words as remained of unorthodox meanings, and so far as possible of all secondary meanings whatever.

This comes from the appendix titled “The Principles of Newspeak”

In their anti-copaganda media guide, Mia Henry, Lewis Raven Wallace and Andrea Ritchie add warnings about police statistics on “crime”, fear-mongering about “rising crime/crime epidemic”, and the police’s criminalizing language:

Crime does not equal violence and harm and not all harm and violence is crime. Crime statistics both overestimate and underestimate violence and harm. Most violent crimes are not reported to police, most things designated as crimes don’t involve violence or harm, many things that are violent and harmful are not crimes, and most crime statistics don’t include violence by police. As a form of “copaganda,” police conflate multiple things to construct a narrative of “out of control” crime—homicides, property crimes, public order offenses. They also frequently focus on the categories of “crime” that are increasing, and not on those that are decreasing. In addition, crime statistics are created and influenced by police—including through what areas and offenses they focus on policing. We also know that crime statistics are deliberately manipulated by police with no independent verification of their numbers.

A lot of news coverage reinforces fear about interpersonal violence, making it seem, mysteriously, that violence has been on the rise every year since forever (when in fact violent crimes reported to police are currently near a 20-year low). While the pain and fear felt by individual victims is real, the narrative of constant rising crime becomes a justification for expanding police powers. Be wary of listing homicide rates in a given year in articles about police budgets; these numbers are too often presented to justify more policing (even when they are falling; even when more policing is proven not to help).

Cops target certain areas, then report higher crime in those areas, reinforcing stereotypes about “safe” versus “unsafe” neighborhoods, usually characterizing low-income Black and Brown neighborhoods as “unsafe” or “crime ridden.” Also watch out for dehumanizing police terminology such as referring to people as “criminals,” “males” and “females” instead of men, women, girls or boys, young people as “juveniles,” accused people as “suspects,” and people who have been convicted as “dangerous” or “offenders.” Same goes for words that define people by the crime they are accused of: “prostitute,” “robber,” “assailant.” These are terms the criminal legal system uses to dehumanize and criminalize.

At a more straightforward level, some revolving doors have been created between the media industry and policing: for instance, for forty years John Miller has been switching back and forth between getting jobs in police departments such as LAPD and NYPD, and working for mainstream outlets like NBC, ABC News and CNN.

But this first dimension of copaganda goes even further, because police departments in major cities like Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles have huge budgets and resources dedicated solely to PR (Public Relations), with PR teams made up of dozens of employees tasked with managing public communications and shaping public perceptions via propaganda, as well as questionable academic “experts” that form an “ecosystem of validation”. Alec Karakatsanis ties together the capitalist/productivist madness of news/media production, Stuart Hall’s argument about “primary definers” which I’ve mentioned several times in previous chapters of this research, and the extended PR campaigns and apparatuses of the police:

I was contacted by a lead news anchor for a local television station (…) as well as by several local and national nightly television news producers. I learned a lot from these conversations, but I want to focus on one thing in particular: they face enormous pressure to fill 20-24 minutes of programming several times per day (for each 30 minute local newscast). Depending on the station, this can include a morning news show, a dinner-time news program, and multiple late-evening news shows. It’s not uncommon for even small local tv news to have shows at 6:30am, 6:00pm, and 11:00pm. A mid-market anchor I spoke with works for a station that does several hours of news in the morning, 90 minutes in the evening, and 60 minutes late at night. In speaking with other producers, I learned that it is very common for mid-market news stations to produce even more content than that each day. National cable news producers face a different kind of crunch, but some of the pressures operate in similar ways with respect to their coverage of public safety.

Another producer explained to me that police public relations employees do not just call reporters and tell them about a story. When police give stories to the media, they often contain video, audio, screenshots of documents, or other easy visuals. Police and prosecutors also routinely have teams ready with (often ludicrously inaccurate) charts and graphics showing supposedly relevant statistics. Police (and DA Offices, which have their own publicly funded PR teams) also routinely pay spokespeople to be briefed and prepared for sound byte interviews, or otherwise make available employees to ensure that there is a person who is prepared to be on camera for a news interview or to a person who can give a quote or spend time with the reporter “on background” to shape the reporter’s understanding of the story. I talk “on background” a lot with dozens of reporters every month, so I know how time consuming it can be to provide context to news reporters who are not specialists in criminal law.

The many thousands of public relations employees in police departments across the U.S. understand how to make things easy on busy journalists. This intervention in news production through the sheer brute force of the content they produce should be seen as one of their chief functions.

Once one starts to think about the reality of how news gets produced every day by busy people, one understands that ideological support for police is often not the most important reason that police exercise such influence over the content and volume of local news. And once one understands even a little bit about how daily news is produced one understands that it isn’t that difficult to manipulate it if you have a lot of money: you produce things for the news, in a format that allows reporters, editors, and producers to have as much content as they can have with as little work as possible. There are many ways to refine the points I’m making here, including understanding which kinds of stories lend themselves best to video, mapping the ideology of particular reporters and stations, having your finger on the pulse of current news trends and the local zeitgeist, etc. The best police PR departments are more sophisticated in understanding these dimensions. But the basic point that police departments and their media consultants understand is this: we can shape the news simply by producing content and sending it to news professionals.

For more excellent analysis from Alec Karakatsanis, see his “Copaganda Newsletter”, especially the following exposés:

- How the Media Enables Violent Bureaucracy: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

- The Big Deception: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

The police uses these enormous PR resources to whitewash their reputation by painting cops as heroic, fun-loving, relatable and friendly members of the community that are admirably dedicated to the greater good. Palika Makam offers some examples of this image-work through social media:

Sometimes copaganda is created by police officers themselves, like this country music video released by the Metro Nashville Police Department that features Sergeant Henry Particelli singing with his guitar as people held signs that read “Peace” and “United We Stand, Divided We Fall.” That police department and many others around the country are turning to social media posts to help counter negative narratives and boost images, like this one, where white police officers pose with a Black child holding a Black Lives Matter sign, or this one from Austin, which shows police officers with all the thank-you mail they claimed to have received from members of the community. Other times, social media videos of police officers kneeling, hugging protesters, or posts of them offering snacks and their tears to little Black girls and boys, as the fearful children shake and cry, are promoted by the general public, and even allies and activists. The focus of these videos is supposed to be on the kind nature of individual police officers, but it’s important to remember that each friendly officer also has a gun on their hip and holds qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that, as explained by The Appeal, can effectively shield officials like police from accountability for misconduct, such as when they use excessive force. Take, for example, the Ohio “dancing cop,” a white police officer who went viral in 2015 for a video in which he danced outside with Black children. That officer was investigated and eventually cleared, in 2019, after body camera footage surfaced of him punching a Black man in the face.

We’ve also seen numerous examples from around the country where police officers kneel with protesters one minute and abuse and disregard their constitutional rights the next. A demonstrator in Orlando shared an image of officers praying with protesters, with the text: “Literally 45 minutes later [members of the department] maced us in the face for the crime of standing in their vicinity.” Another protester in New York City tweeted a video of police officers taking a knee, with the text: “They beat the living shit out of us one hour after this.” And after the highest-ranking uniformed NYPD officer was filmed on his knees linking arms with protesters in the street, reports continued of his department kettling crowds, beating them with batons, and pepper-spraying demonstrators across the city. This pattern raises the question: Are these police officers really standing in solidarity with Black lives or are they engaging in performative displays that subdue the public?

Police PR departments regularly plant and create what Adam Johnson and Nima Shirazi called clickbait copaganda, with a number of recurrent tropes, strategies and stunts, such as:

a) “Publishing tales of how difficult the police have it as PR-intensive trials of police officers are being carried out in the public” [Adam Johnson]

b) Pinkwashing and other diversity-boosting/washing stories that give the appearance of reforms (and reformability!) or respect/sympathy – e.g. the NYPD’s Autism Awareness day/car – to whitewash the systemic/structural problems in policing (racism, sexism, ableism, etc.)

c) “Christmas gift surprise” and “saving kittens/puppy/ducklings/birds/small animals” stories

d) Dehumanizing/smearing police shooting/violence victims by getting as much dirt on them out as possible (e.g. the cases of Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Sam Dubose, Charly “Africa” Keunang, and Freddie Gray)

f) Humorous and memetic social media tactics, “presenting an ersatz image of police humour and officers au fait with the latest trends in memes and youth culture” (e.g. dancing, lip syncing, singing,

g) In times of large-scale protests – especially ones against police violence and racism, such as the 2020 George Floyd Uprising -, police PR goes into overdrive in order to reaffirm the absolute moral superiority and trustworthiness of cops and demonize and criminalize protesters/critics (especially ones that don’t back down in front of these manipulation/PR tactics)

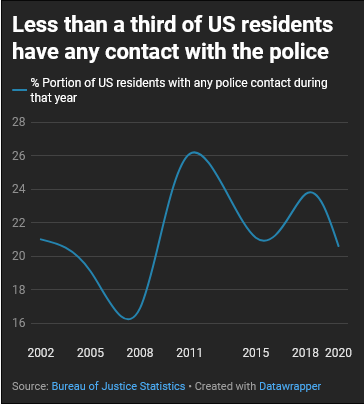

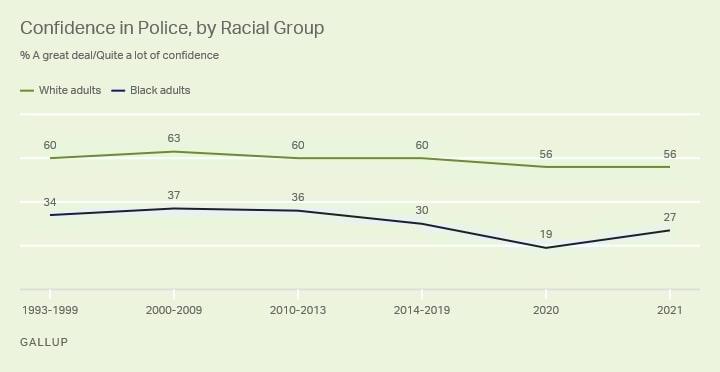

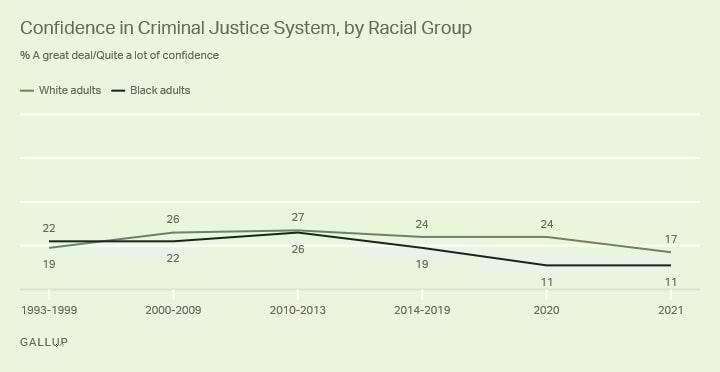

As you can see in the data and charts below ( obviously the usual epistemological caveats apply as with any aggregate stats), the majority of U.S. residents actually have little contact with the police (less than a third have any contact in a given year, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ reports since 2002). The overall confidence in the police is at record lows since the start of the current decade, although there’s a gap betwen white and black residents in particular. For obvious reasons (white supremacy and its inherent anti-black police brutality/oppression), historically black people have had low confidence in the police, whereas a majority white people did trust them. It would be interesting to look at how it (potentially) varies with respect to class, but that’s beyond the scope of this topic. Moreover, across the whole population there’s been very low confidence in the (in)justice system for decades. The US state and police are aware of this, which is why for the past 50 years there’s been so much money and resources put into copaganda. For the National Institute of Justice – R&D branch of the U.S. Dept of Justice – Jarret Lovell openly confirmed/admitted the role and necessity of copaganda/police PR in 2002:

Most citizens have little contact with law enforcement officers and their opinion of the police is often formed by the mass media’s portrayal of our functions. (…) The goals of [the Department] are to maintain public support … by keeping the avenues of communication among the department, news media and citizenry open. The objectives … are to utilize the media when attempting to stimulate public interest in departmental programs involving the community [and to] promote a feeling of teamwork between the police and media.

You can find the link to data sources (from the Bureau of Justice Statistics) here.

Source: Gallup.

We’ve seen how the news/social media copaganda tries to shape people’s perceptions of the police, and we now turn to the other face of the copaganda coin that comes from the culture industry: fiction and entertainment doing the same image-work and mythmaking described above but in an even more indisious way, i.e. whitewashing and glorifying/romanticizing the police, policing, surveillance, as well as secret/intelligence services and the army, by manipulating people’s everyday cultural socializations. As Lucas DeRuyter notes, “there’s so much pro-police propaganda that it’s reached ubiquity, meaning it is largely unnoticed by viewers and accepted as a part of the entertainment landscape”.

Entertainment is supposed to be an end in itself, something you can enjoy without worrying about realism, subtexts, ethical or political considerations, or the fact you’re being sold specific myths and narratives about modern society – largely in order to make you consent and conform to the prevailing social order and hierarchy. A lot here could be said from critical theory perspective, drawing on Adorno and Horkheimer’s critique of the culture industry, Debord’s analysis of the “spectacle”, Kracauer’s work, and more. This is beyond the scope of my current knowledge/research (I still have a lot more reading and studying to do to grasp these contributions, before I can start talking about them in an interesting way), and also not my aim here, which is more about providing a descriptive/empirical and critical documentation/overview of copaganda in its various forms.

I’ve talked a lot about how people’s ordinary, everyday cultural and ideological socializations – especially growing up or over extended periods of time (a decade or several decades of one’s life) – can have a major impact on their worldviews and politicizations (in a word, the various ways, framings and forms of agency through which people make any topic/thing a contested “political” issue, as well as the equally diverse modes/modalities/mediations of action and interaction that revolve around it – yeah, it’s one of those extremely abstract conceptual constructions, sorry…). Interestingly, Johanna Blakley argues that entertainment – and/or what I’d call the culture industry – might have an even deeper impact on people’s perceptions and politicizations than news media:

Entertainment is probably much more effective in terms of changing people’s values and attitudes and beliefs and behavior, even than news programming. When you’re tuning into news programming, you’re often trying to find news that represents to you a world you understand. But that’s not why people tune into entertainment programming. It kind of gets under that radar.

As James Baldwin said sixty years ago with (dis)respect to Hollywood’s films:

These movies are designed not to trouble, but to reassure; they do not reflect reality, they merely rearrange its elements into something we can bear. They also weaken our ability to deal with the world as it is, ourselves as we are.

Cultural/entertainment/fictional copaganda paints an image of policing (and cops/law enforcement themselves) as “in the last instance/in the end always heroic, well-meaning, and infallible”, i.e. it’s not that they don’t make mistakes or aren’t flawless in some ways, but that in the end, at the end of the show or the movie, they’ll get it right and turn out to be brave and bold fights for justice and “law and order”. Moreover, following Blakley’s argument about the insidious, indirect impact of TV shows on public attitudes, Eric Deggans says that they encourage “audiences to empathize with some parts of the process, while keeping more troubling aspects firmly out of view.” This is a relevant point, although a) even when troubling and fucked-up stuff is put front and center, they’re still celebrated as legitimate forms of the police’s discretionary power (more on this later), and b) needless to say there are certain limits to making broad generalizations about the U.S. context without taking a look at sociocultural differentiations around things like ‘race’, gender and class.

As pointed out by Alice Nuttall and Constance Grady, at the beginnings of modern mass media near the end of the 19th century, depictions of the police were the opposite of the heroic portrayals of law enforcement within today’s copaganda:

Early representations of the police were often unflattering; in A Study in Scarlet, the first Sherlock Holmes story [published in 1887], detectives Lestrade and Gregson are portrayed as ridiculous figures, and their incompetence is highlighted by Holmes when he is able to perfectly describe the murderer from a single glance at the crime scene.

In 1910, the International Association of Chiefs of Police was moved to adopt a resolution condemning the movie business for the way it depicted police officers. The movies, the IACP complained, made crime look fun and glamorous. Meanwhile, the police were “sometimes made to appear ridiculous.”

It was true: The movies did tend to make the police look ridiculous in the 1910s. From 1912 to 1917, the incompetent Keystone Cops bumbled their way across the silent screen. From 1914 to 1918, animated Police Dog shorts showed a police force unable to prevent adorable Officer Piffles (a good dog) from getting his owner into one scrape after another. And in 1917’s Easy Street [the movie is available here!], Charlie Chaplin’s tramp-turned-police-officer was only able to save his girl from a mob of criminals after accidentally sitting on a drug addict’s needle and picking up superpowers from the force of the inadvertent injection.

The ridiculous police of 1910s pop culture didn’t come out of nowhere. The police of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were widely understood to be a corrupt gang, and not without reason. The infamous Lexow Commission of the 1890s, which ran more than 10,000 pages long, found that the police extorted $10 million from the public each year in New York State alone, and that they regularly harassed the citizenry rather than trying to protect them. That report drove 30 years of police reform efforts and gave a young Theodore Roosevelt the chance to build his reputation on cleaning up the New York City Police Department — but for much of the public, the police’s reputation as a pack of hired goons at worst and incompetent bumblers at best had already been set.

Unfortunately, as with many other things the rest of the 20th century would turn crime and detective fiction into insidious apparatuses of authoritarian conformism and celebration of the prevailing social order, mass-produced as commodities, as Adorno and Horkheimer noted in the 1940’s. Grady writes that:

Decades of reform helped change the public’s perception of the police. But it also helped that the movie industry, eager to escape police censorship, began to police itself. Studios needed police cooperation to cover up their stars’ misdeeds. They also needed to get shooting permits. They had plenty of motivation to play nicely with the police. So the policeman as incompetent bumbler began to fade away from the movies.

Lucas DeRuyter argues that the rise of the superhero comic book genre in the 1930s had an indirect influence on the transition from slapstick/comedic depictions to copaganda:

In the US, modern-day copaganda began to take form in 1938 with the release of the first Superman comic, which featured the paragon of moral virtue acting outside of the law to address issues that the police couldn’t handle. While this one piece of children’s media inadvertently advocating for an unchecked police force isn’t inherently a problem — and is inevitably complicated by additional factors, like the fact that Superman was a benevolent figure written by Jewish writers at a time when Nazism was climbing to power — the rise of similar stories not imbued with coding by marginalized authors helped create a media landscape that tells kids that the world’s problems can be fixed by giving authority figures more power and freedom, which is definitely a concerning trend.

That being pulpy children’s media, though, superhero comics were relatively unexamined by broader society at their inception, and most of the American public’s perception of the police was colored by more mainstream pieces of media like Keystone Cops, a series of slapstick silent films that depicted law enforcement as being wildly incompetent.

In the context of the postwar cultural authoritarianism and anticommunism, fearing the spectres of the USSR internationally and powerful workers’/union and other movements at home, the U.S. media and culture industry started shifting its portrayal of policing with the rise of the modern “police procedural” from the 1950s onwards. Grady continues, highlighting that this new genre was built by the police and as covert PR for them:

What cemented the idea of the hero cop in the American imagination was the modern cop show, starting with 1951’s Dragnet. And as many critics have already shown — including, notably, Alyssa Rosenberg in her in-depth study at the Washington Post — the modern cop show was the result of a close relationship between Hollywood and the police.

The premise of Dragnet was that it was revealing to the world the authentic truth of what it is like to be a police officer, fighting crime. “Ladies and gentlemen, the story you are about to see is true,” showrunner, star, and narrator Jack Webb promised at the beginning of every episode. And as Webb’s character, the stalwart LAPD detective Joe Friday, went about his work, he was surrounded by real cop cars and real cops acting as extras in the background of his scenes. Famously, the LAPD checked Webb’s scripts for authenticity.

But as Rosenberg laid out, the LAPD’s help came at a cost. Webb submitted every script to the LAPD’s Public Information Division for approval before shooting, and any element they disliked, he would scrap.

The politics of Webb’s Dragnet were not neutral. “What Dragnet offered the American public,” as the pop culture scholar Roger Sabin writes in his book Cop Shows, “was a vision of the police force as a ‘stabilizer’ in society, made up of honest men (mostly men) dedicated both to keeping the bad guys in their place, and to the more abstract values of law and order.” Dragnet presented the police to the public the way the police wanted to be seen: as aspirational heroes.

In 1951, the same year that Dragnet premiered, multiple members of the LAPD assaulted seven civilians, leaving five Latino men and two white men hospitalized with broken bones and ruptured organs. Racially motivated violence against civilians was and still is part of the reality of the police force. But Webb and his collaborators at the LAPD deliberately elided that reality, giving us the fantasy of the hero cop instead.

As Aaron Rahsaan Thomas explains:

The past 60 years have seen shows like Dragnet (1951–59), The Untouchables (1959–63), and Adam 12 (1968–75) establish a formula where, within an hour of story, good law men, also known as square-jawed white cops, defeat bad guys, often known as poor people of color. (…) The original Hawaii Five-O (1968–80) and Kojak (1973–78) inherited this DNA, and even as procedurals became increasingly nuanced, using compelling character work and gritty visuals, shows like Hill Street Blues (1981–87), Miami Vice (1984–89), and Cagney & Lacey (1982–89) were, for the most part, told from the point of view of white cops occasionally interacting with people of color who were, at best, one-dimensional criminals, colleagues, bosses, sidekicks, and best friends. Even when blackness was not equated with criminality, it was often supplemented by an inhuman lack of depth or presence. [links and dates added]

It’s not lost on me that – in a moment of quintessential liberal hypocrisy and irrationality – Thomas is himself the co-creator and showrunner of CBS’s S.W.A.T. which firmly belongs to the Dirty Harry style of copaganda (i.e. cop goes completely bloodthirsty and lawless “but gets results”, an ideological legitimization of literally limitless police discretionary/arbitrary barbarism). During the anti-police-brutality uprising of 2020, Craig Gore, a writer for S.W.A.T. (and Chicago P.D.) was fired from a then-forthcoming Law & Order spinoff for jokingly threatening protesters online. Anyways, in the context of the rise of copaganda in the U.S. culture industry, we can’t overlook both the “War on Drugs” (started by Nixon) and the “War on Terror” (after 9/11). The former was a massive background to the 1970s-1990s cop shows, many of which became a propaganda apparatus for it:

As violence in American cities increased in the 1970s and 1980s, many programs justified and sometimes even celebrated officers who engaged in brutality or killed suspects, while almost never telling stories from the perspective of those who were on the other side of police officers’ guns and batons. Officers were also depicted longing for an escape from cities that they viewed as rife with crime, and Hollywood frequently depicted cops as being contemptuous of civilian authorities, courts, and any other figures or institutions that dared provide oversight.

Decades later, those attitudes are reflected in the actual, real-life police officers who “protect and serve.” Most police officers do not live in the cities they work in and police departments, and especially police unions, have fiercely resisted oversight and accountability.

“Movies, television and novels have trained audiences to excuse almost any police shooting,” Rosenberg wrote in her five-part series on police and pop culture in 2016.

This growing cultural normalization and celebration of boundless police brutality was of course fundamentally rooted in and appealing to white Americans’ racist and authoritarian anxieties in the 1970s and 1980s context of a global structural crisis of US-dominated capitalism, the shock of white conservative America at seeing the student, civil rights, black power, gay, feminist, and antiwar/anti-imperialist movements, civil rights being granted to nonwhite people and the (partial) desegregation of public schools, the increasing presence of nonwhite minorities in the suburbs in many regions of the country, and so on:

These shows presented the drug trade as a global danger imported from outside America, often from south of the Mexican border. Perhaps not coincidentally, a Gallup poll in 1989 found 63% of Americans saw drug abuse as America’s number one problem, reflecting a rising hysteria about crack cocaine and drugs from Mexico (by 2014, that number would be down to 1%).

Shawn Ryan, creator of The Shield, says there was likely an additional reason that public sentiment regarding the war on drugs shifted towards leniency and understanding for users back then. “I think it was easy for white America to have one point of view about the drug war when it was mostly hitting minority communities,” says Ryan. “What really changed in the mid-2000s was the opioid epidemic that began to affect people, especially white people in rural communities. And the minute someone in your community is dealing with these problems, you tend to look at the problem differently.”

Despite advances in more nuanced portrayals, research showed TV still wasn’t providing an accurate picture of drug enforcement. In 2011 – the 40th anniversary of the war on drugs — The Lear Center released an analysis looking at episodes of popular shows like Law & Order and CSI: Crime Scene Investigation.

The study, called The Primetime War on Drugs and Terror, found these shows failed to reflect how non-white people are disproportionally arrested and punished in drug enforcement. According to the study, Black people were 13 percent of drug users but 43 percent of those jailed for drug violations. Another analysis the Lear Center released [in 2020] with Color of Change, Normalizing Injustice, found a similar dynamic.

These series may have been showing that the drug war wasn’t working, but they weren’t depicting an important reason why it was failing: disproportional punishment given to people of color and the poor.

In one study, [Dr. Franklin T. Wilson] and his colleagues examined the depiction of police use of force in 112 cop films across 40 years, beginning with Dirty Harry in 1971 and ending in 2011, a year prior to the death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teenager who was shot and killed by a vigilante neighborhood watch member.

“In the end we examined 468 police use of force scenes,” Wilson said. “We have found that the vast majority of those who are on the receiving end in depictions of police use of force are white males. Therefore, if the common person rarely sees the depiction of African Americans as the recipient of police use of force, the concept is symbolically removed from their conscience.”

Americans saw real, living, breathing Black people as criminals worthy of arrest in Cops, but rarely saw Black people being harmed by police in movies, making it more difficult for them to conceptualize the reality in which police officers actually are using excessive force against innocent Black people.

“These entertainment media depictions of police use of force have helped to cultivate a sense of reality that does not really exist when it comes to police use of force, often resulting in a belief that certain uses of force cases are rare,” Wilson said.

When Hollywood did depict Black characters in fiction, they were most often portrayed as drug dealers, “thugs,” gangsters, pimps, or otherwise violent and unsympathetic criminals.

“We know through cultivation theory research that unless a person has a personal experience with an issue, the more one consumes specific messaging, be it imagery or statements of information, the more they are likely to adopt it as fact,” Wilson said. “If you couple all of this with the fact that law enforcement related programs have accounted for 20-30% of programming since the 1970s, it’s hard to imagine it has not had an impact.”

In other words: If one of the main narratives Americans are being shown on TV and in movies is the message of “cops are good and use force only when necessary” and “Black people are violent criminals,” then it’s hard for it not to seep into Americans’ actual perception of law enforcement.

Since its launch in 1989 (it’s unfortunately still running after being “cancelled” – for only three months… – in 2020 because of the George Floyd protests), Cops has been one of the most popular TV programs about law enforcement in the U.S. But it’s arguably even worse than the majority of copaganda programs, because it’s a so-called “reality” show pushing the mythmaking – racist stereotyping and brutality, heroic depiction of cops, fearmongering about “crime waves” and emphasizing “permanent” threats and anxieties – of modern policing to an even stronger level (for people who buy into it):

[Cop] shows often excuse all use of excessive force as justified, making their officers look like action heroes who need to be rough with suspects. This ramps up drama, but in the case of Cops or Live PD, these are real people, most often with addiction issues, not one-dimensional “bad guys”. And this is where the problem lies. Police in the media teach us to see all criminals, in both fiction and real life, as stereotypes.

Cops was notorious for showing the featured officers violating rules of conduct, even though part of the agreement with the show was that precincts got to make the final cut. When this happens, the viewing public thinks this violence is normal behavior. This is not only acceptable as an officer, but expected. So when we see video footage of police using force in a situation where it would otherwise be unwarranted, we have already been trained through media to believe that this is what a good cop does. For them to keep “us” safe, violence is the only option. So even with cops making the final cut, this is the message that they want shown; if these gross violations are what make it on the air, imagine what doesn’t. Also, in its later seasons, some featured officers said that Cops was a major factor in them deciding to join the force. So bad policing was their foundation.

Live PD, the cinematic offspring of Cops, was an even more sensationalized look at policing, and quickly became A&E’s top rated show. In what almost feels like propaganda for the never ending drug war, both shows’ arrests were primarily drug centered. With mostly members of marginalized communities and poor whites as the targets for the police, the officers involved get to appear as if they are cleaning up the streets. This enforces the narrative that crime, and drugs especially, are only prevalent in poverty stricken areas. The show gives the cops’ actions a shiny veneer of justice, while they mostly entail arresting addicts and low level offenders. Some officers were even told by the camera crew on Cops after more simple arrests to take suspects out of their vehicles and add heart-to-hearts for dramatic effect so that they could pad time in the segment of the episode. The show props up the idea of these cops as heroes who go out every day to make a difference, when in reality, the empathy displayed is staged.

(…)

Police procedurals provide an easy story set up and make the drama simple to follow. Our protagonists are the cops who relentlessly pursue justice. All their actions in that pursuit are justified, so we can then excuse anything that we would normally see as dangerous behavior. Centering narratives around only one view point in a complex issue like crime makes it appear more cut and dried then it really is. Even when they do show that the justice system has flaws, the only flaws they focus on are that police have too many rules that restrict them.

[Cops] embraced racial stereotypes, depicting predominantly white police officers arresting primarily Black and Brown suspects, leading viewers to believe that people of color committed more crimes than they really did. The world of Cops was quite literally, very Black and white: Police officers were the “good guys” and their suspects were depicted as the “bad guys” who deserved what they had coming to them.

Cops premiered on Fox on March 11, 1989, and almost immediately became a huge hit. The show felt “real,” and for many viewers, it was. Americans largely accepted such portrayals of police officers—and suspects—without a second thought and held overwhelmingly positiveviews of law enforcement.

But those media depictions are often misleading and divorced from reality. Research has found that Cops depicted drug crimes, prostitution, and violent crime as being far more common than in real life, showed cops as being more effective at making arrests and solving crimes than in real life, and presented the use of excessive force as good policing. A 2007 analysis of the show also found that the series typically depicted men of color—who made up 62% of offenders on-screen—as violent criminals and white men as non-violent criminals.

More than nine in 10 police officers shown on Cops were also white men (92%), reinforcing the stereotypes of white men protecting society from Black and Latino men. While playing into harmful tropes of Black men, the show also celebrated police officers, delivering them a publicity coup. The show lionized police officers to such a degree that it was once described as “the best recruiting tool for policing ever.”

Unsurprisingly, Emma Rackstraw found that “arrests for low-level, victimless crimes increase by 20 percent while departments film with reality television shows, concentrated in the officers actively followed by cameras.” A similarly grim phenomenon is what Citations Needed media critics Adam Johnson and Nima Shirazi called “Vigilante TV News” in their dedicated episode about it:

For decades, local and national media, from nightly news broadcasts partnering with Crime Stoppers to primetime TV shows like America’s Most Wanted, have warned consumers of dangerous criminals on the lam, lurking outside our neighborhood grocery stores or their children’s schools. The FBI and police departments throughout the country, the public are told, are doing everything they can to catch The Bad Guys — they just need a little help from concerned, responsible, and vigilant citizens like you. Cue the calls to action imploring people to submit tips through hotlines, law enforcement websites, and social media. (…) News and pop cultural media deputizes and urges listeners, readers, and viewers to act as neighborhood vigilantes. (…) This instills a climate of constant, unnecessary fear; presents the current US and criminal legal system as the only option to reduce crime; excludes crimes against the poor and working class like wage theft, food and housing insecurity, and lack of healthcare; and inflicts unjust harm upon the subjects of these anonymous tips.

By the way, I know there would be important discussions and points to add here about the long-term settler colonialist and white supremacist underpinnings of white AmeriKKKa’s cultural obsession with para- or non-state brutal vigilantes, militias and policing, but this is beyond my own knowledge at the moment. However, I’d be happy to add links here to relevant materials/conversations about this. Let me now continue with the “War on Terror”, why even some of the better and more “nuanced” shows are still fundamentally problematic, and how all this copaganda makes people believe wrong and dangerous things about crime and policing in the U.S.

21st Century copaganda grew out of this shameless celebration of police brutality and authoritarianism, which were both obviously shaped by a new permanent “threat” and hence permanent state of exception” (after other permanent “threats” such as slave rebellions/emancipation, the workers’ movement and communism, the civil rights and black power movements, etc) : the so-called “War on Terror”. Back in 2007 Jane Mayer wrote a scathing piece about 24 (2001-2014), the longest-running U.S. espionage- or counterterrorism-themed television drama and the quintessential “War on Terror” product of the 21st century culture industry:

For all its fictional liberties, “24” depicts the fight against Islamist extremism much as the Bush Administration has defined it: as an all-consuming struggle for America’s survival that demands the toughest of tactics. Not long after September 11th, Vice-President Dick Cheney alluded vaguely to the fact that America must begin working through the “dark side” in countering terrorism. On “24,” the dark side is on full view. Surnow, who has jokingly called himself a “right-wing nut job,” shares his show’s hard-line perspective. Speaking of torture, he said, “Isn’t it obvious that if there was a nuke in New York City that was about to blow—or any other city in this country—that, even if you were going to go to jail, it would be the right thing to do?”

Since September 11th, depictions of torture have become much more common on American television. Before the attacks, fewer than four acts of torture appeared on prime-time television each year, according to Human Rights First, a nonprofit organization. Now there are more than a hundred, and, as David Danzig, a project director at Human Rights First, noted, “the torturers have changed. It used to be almost exclusively the villains who tortured. Today, torture is often perpetrated by the heroes.” The Parents’ Television Council, a nonpartisan watchdog group, has counted what it says are sixty-seven torture scenes during the first five seasons of “24”—more than one every other show. Melissa Caldwell, the council’s senior director of programs, said, “ ‘24’ is the worst offender on television: the most frequent, most graphic, and the leader in the trend of showing the protagonists using torture.”

Jack Bauer was almost caricatural among 21st century shows in terms of celebrating the use of torture and the most brutal methods, but copaganda doesn’t have to be this extreme to be problematic. The majority of the most popular contemporary police shows – inclduing the NCIS, CSI and Law & Order franchises, The Mentalist, Without a Trace, Criminal Minds, Mindhunter, Hawaii Five-o, Dexter, Bones, Person of Interest, The Blacklist, Blue Bloods and more – were aptly described by John Oliver as “complete fantasy” where “exceptionally competent cops [are] working within a largely fair framework that mostly convicts white people”, “presenting a world where the cops can always figure out who did it, defense attorneys are irritating obstacles to be overcome, and even if a cop roughs up a suspect, it’s all in pursuit of a just outcome”

Oliver was talking about Law & Order specifically, and clearly it’s perhaps the one where the criminal/injustice/policing system is depicted most uncritically, but this applies to the majority of modern cop shows in the West (especially in the U.S.) even if some of them try to show some less positive aspects or sides of the police. Ultimately they always end up saying “look at these outsanding, extremely competent and intelligent and brave cops/detectives/units that are ready to do whatever it takes to get the Bad Guy.” In other words, any character flaws or scenarios of injustice are never really framed as sytemic but at worst as there being “Bad Apples”.

This contemporary style of depicting cops and detectives as hyper-competent and bold has been shown to impact audiences’ perception of policing: in a 2015 study, Kathleen Donovan and Charles Klahm IV found that “viewers of crime dramas are more likely to believe the police are successful at lowering crime, use force only when necessary, and that misconduct does not typically lead to false confessions.” Here again some of the critical analysis from the Citations Needed podcast is relevant:

Episode 94: The Goofy Pseudoscience Copaganda of TV Forensics

Since the early 2000s, a spate of forensics-focused TV shows and films have emerged on the pop culture scene. Years after Law & Order premiered in the nineties, shows like CSI, NCIS, and The Mentalist followed, trumpeting the scientific merit of analyzing blood-spatter patterns, reading facial and bodily cues, and using the latest fingerprint-matching technology to catch the bad guy.

Yet what these procedurals neglect to acknowledge is that many of these popular forensic techniques are deeply unscientific and entirely political. Spatter pattern-matching, firearms analysis, hair analysis, fingerprint and bite mark analysis — they’re all pretty much bullshit with little scientific merit and they’ve helped contribute to the wrongful convictions of thousands of people. Indeed, a 2019 study by the Innocence Project found that quote unquote “forensic science” contributed to 45 percent of wrongful convictions in the United States later overturned through DNA evidence and false or misleading forensic evidence was a contributing factor in 24 percent of all wrongful convictions nationally, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, which tracks both DNA and non-DNA exonerations.

The general population — informed almost entirely by reality TV, television dramas, and movies — assumes that the point of forensics is to “catch the bad guy” but it can’t be stressed enough how much this is not the case. It’s a marketing tool to lend scientific verisimilitude to what is very often just circumstantial, hunch-based police work

Criminal Minds. Inside the Mind of a Serial Killer. Inside the Criminal Mind. Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez.These are the titles of popular television series, fictional or otherwise, or documentaries that rely on the work of so-called criminal profilers. They’re all premised, more or less, on the same idea: That the ability to venture inside the mind of an individual who’s committed a horrific act of violence — say, serial murder, rape, kidnapping — is the key to figuring out why that crime happened in the first place. This theory may sound promising at first blush; after all, the highest echelons of law enforcement in the US continue to use criminal profiling tactics to this day.

But the reality is that, despite their prevalence in law enforcement both onscreen and off, criminal profiling techniques are largely ineffective, and in many ways, can be dangerous. Failing to consider institutional factors such as a culture of violence and easy access to weapons, patriarchy, austerity and other social ills that contribute to and reinforce violent crime, criminal profiling focuses almost exclusively on individual experiences and psychological makeup. Meanwhile, it characterizes “criminals” not as people who’ve been shaped by this social conditioning, but as neuro-deviants whose psychological anatomy is just plain different from yours or mine.

In 2020, Color of Change – an antiracist organization/collective – did a systematic study of 26 major police and crime-related series from ABC, FOX, Amazon, NBC, Netflix and CBS, focusing on the 2017-2018 season (a total of 353 episodes were examined). Here are the major misrepresentations and problems that they found:

Normalizing Injustice as Standard Practice & Cultural Norm

“Almost all series depicted bad behavior as being committed by good people, thereby framing bad actions as relatable, forgivable, acceptable and ultimately good. Remarkably, the data show that scripted crime series depicted “Good Guy” Criminal Justice Professionals committing wrongful actions far more than they depicted “Bad Guys” doing so. The likely result? Viewers feeling that those bad behaviors are actually not so bad, and are acceptable (even necessary) norms.”

“Series generally framed wrongful actions as merely the cost of doing business when it comes to solving crimes, catching the bad guy and fighting for justice.”

“Most series conveyed the idea that whatever a [protagonist] does is inherently “right” and “good” by virtue of it being done by a CJP, especially a beloved main character.”

“Across the genre, it was the norm for CJPs to commit wrongful actions, but it was not the norm for CJPs to challenge them—that is, committing wrongful actions was part of what all CJPs were depicted as doing as part of their job, but challenging (or even acknowledging) wrongful actions was not.”

“Several series seemed to use people of color characters as validators of wrongful behavior by either depicting people of color CJPs as perpetrators or supporters of wrongful actions, or by depicting them as tacit endorsers.”

Misrepresenting How the Criminal Justice System Works & Rendering Racism Invisible

“Consistently, series omitted stories and references about the harms that legal criminal justice procedures and practices cause, generally misrepresented key aspects of how the criminal justice system works and did not represent the status quo system as necessitating reform. There were also few depictions or conversations about racial disparities in the criminal justice system or in terms of crime itself. Race was also largely invisible as an issue in the workplace and in the lives of characters, though several series featured central characters played by people of color. “

“Viewers were least likely to see victims of crimes portrayed as women of color. Black women were rarely portrayed as victims: 9% of all crimes, and 6% of primary crimes. The likelihood that primary crime victims were white men was 35%, white women 28%, men of color 22% (Black men 12%) and women of color 13%.”

“Almost all series conveyed the impression that change is not needed.”

Excluding People of Color & Women Behind the Camera

81% of showrunners were white men, only 37% were women, 9% Black men, and 11% women of color.

But in the same that police abolitionists and other antiracist activists/movements in the U.S. have argued that trying to have more diversity within the police is ultimately missing the point and a dead end, Black radicals have emphasized how the inherent anti-blackness of U.S. policing can still be reproduced even if some of the protagonists are Black. Here’s Mark Anthony Neal in an essay for Abolition for the People:

In Raymond Nelson’s 1972 essay on Himes’ detective novels, he describes Grave Digger and Coffin Ed as “bad niggers” — symbols of “defiance, strength, and masculinity to a community that has been forced to learn, or at least to shame weakness and compliance.” And indeed, on-screen, Cambridge and St. Jacques’ performances of the duo were given the gravitas of “race men” — these figures, often men, within Black life and culture who were committed to the “race”; they didn’t simply acquiesce to the white power structure that employed them but also offered a healthy skepticism of ghetto hustlers while using their badges and relative privilege to look out for the “least of” in Black Harlem. The extent to which Grave Digger and Coffin Ed were depicted as being embedded in the very fabric of Black Harlem was a refreshing counter to the drive-by treatments of Black life found in most film and television in the era, particularly with regards to law enforcement.

The 1991 film A Rage in Harlem, a third of Himes’ detective novels to be adapted for the big screen, found Grave Digger and Coffin Ed on the periphery of the film’s focus, as if it were a metaphor for the cultural shifts that had seemingly occurred in the previous two decades. In many ways, Grave Digger and Coffin Ed were precursors to the Black-White cop buddy films of the 1980s — think Danny Glover and Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon, or 48 Hours, in which Eddie Murphy played a petty criminal working with a detective (Nick Nolte). Whereas the idea of cop buddy films with two Black actors were not tenable to Hollywood at the time — and would not be until the Bad Boys franchise — the Black-White cop buddy films were more marketable given the success of films like The Defiant Ones (Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis) and the Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder films of the 1970s and 1980s.

Notable about these films, including the Bad Boy franchise with Will Smith and Martin Lawrence, is the way that Black officers were largely evacuated from Black life and community. Though Glover played a family man in Lethal Weapon, there was nothing inherently Black about his life. (In fact, Gibson played the role of the rogue cop.) This could also be seen in the television series NYPD Blue, where James McDaniels portrayed Lt. Arthur Fancy for the series’ first eight seasons, yet there was little attention to his life outside of the precinct. The Law and Order franchise reveals little about the backstory of numerous Black officers played by the likes of Jesse L. Martin, Anthony Anderson, and Ice-T, who has portrayed Sgt. Odafin “Fin” Tutuola for nearly 20 years.

The aforementioned fictional officers exist in contrast to Boyz n the Hood’s Officer Coffey, a Black cop (played by Jessie Lawrence Ferguson) whose disdain for Black youth is palpable. Denzel Washington’s Oscar-winning performance as Alonzo Harris in Training Day is yet another example of a character who is allowed to reign terror on a Black community due to the faulty logic of Black-on-Black crime and the benign neglect directed toward poor and working-class communities of color that renders those communities as complicit in their own pathologies. In such instances, it seems Blacks and others do not deserve to be protected and served.

That such characters were featured in films by Black directors (John Singleton and Antoine Fuqua, respectively) doesn’t change the fact that in much of popular culture, Black officers are no longer race men at all — but, rather, stand-ins for the very anti-Black violence directed at Black communities. As a whole, these characters are complements to the purposes of copaganda, serving as examples of Black exceptionalism on the one hand while suggesting that policing is race-neutral but criminality is not.

I’m obviously not gonna be able to offer an exhaustive breakdown of all shows and so on, I know this text is already kinda endless, but it’s worth mentioning that even shows with more “nuanced” and less problematic depictions of policing – such as The Wire or Brooklyn Nine-Nine –, still constitute copaganda, as Constance Grady explains:

It is also de rigueur for some of the 21st century’s cop shows to argue that there are serious problems in contemporary police forces. Not all cop shows choose to critique their systems: Law & Order and its various spinoffs tend to place their unfailing trust in the system. CBS’s Blue Bloods aired an episode in 2014 in which a Black suspect throws himself out of a third-floor window to frame a blameless white officer for police brutality, the implication being that criticisms of the existing system do nothing but make life easier for criminals and harder for our heroic boys in blue.