As I mentioned in the previous section, I’m not familiar enough with the critical discussions/literature on the “culture industry”, the “spectacle” and modern culture/art (Friedriech Kracauer, György Lukács, Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Bertol Brecht, Guy Debord and the Situationists, Roland Barthes, Oskar Negt/Alexander Kluge, Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, Fredric Jameson, etc.) to get into an in-depth discussion about them here, but I’m still going to provide some notes/thoughts about these important critical perspectives, because they’re relevant for the wide-ranging study of modern propaganda that I’ve been doing. So I hope to come back to this discussion in the future after diving more into this literature, but here’s a first approach.

The reason I include Adorno’s Kulturindustrie and Debord’s spectacle in my investigation of the various dimensions/forms of modern propaganda/media, is the fact that they both tried to outline the contours of 20th century Western society’s domain of cultural and ideological alienation/estrangement (Entfremdung) and pacification/domination:

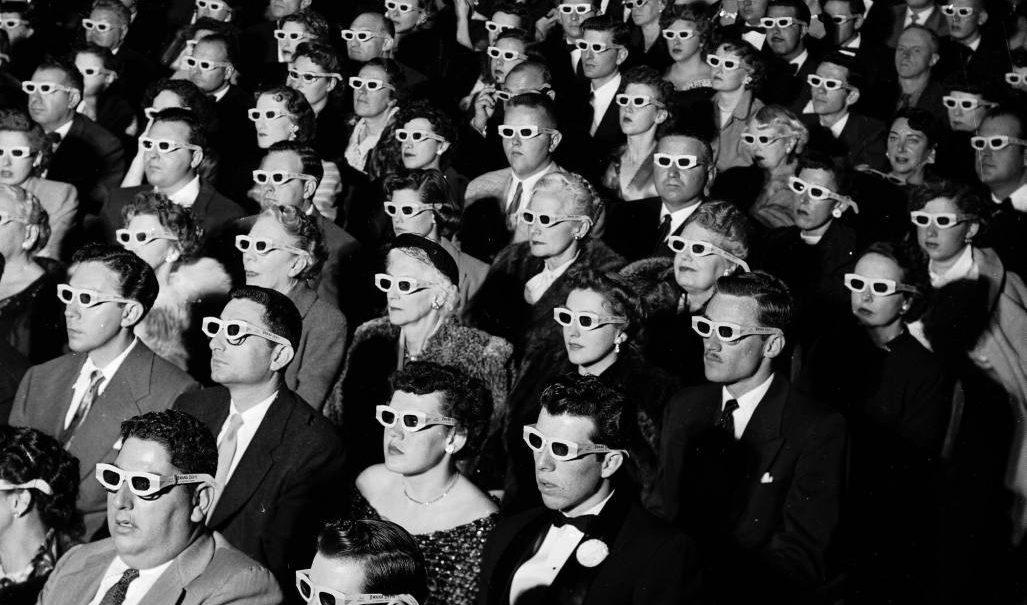

Debord and Adorno both realized that they were confronted by a false form of social cohesion, an unacknowledged ideology designed to create consensus around Western capitalism, a way of ruling society, and, lastly, a technique for preventing individuals, who were just as ripe for emancipation as the state of the productive forces would allow, from becoming aware of that fact. According to Debord and Adorno, the infantilization of the spectator is no mere side-effect of the spectacle and the culture industry, but the embodiment of their anti-emancipatory goals

Anselm Jappe in the SAGE Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory (see reading list)

In this entry Jappe clearly shows how deeply similar Adorno’s and Debord’s perspectives/critiques are (despite relying on different concepts), with the exception of their opposite conclusions on the role and potential of art (I won’t get into all this comparison or the nuances regarding art here, see Jappe’s essay). The content of both the culture industry and the spectacle is, as he writes, “the continous presentation of what exists as the sole possible horizon” (Jappe). Both demand and impose a culture of conformism and passive acceptance and obedience to the existing order and social hierarchy, both colonize everyday life and thus expand the domination of capital outside of work/the production process (including in ‘free time’ and even romantic relationships), both tend to homogenize and trivialize creative/artistic/cultural production.

Both therefore repress (or ‘maim’, ‘mutilate’, as Adorno puts it in Minima Moralia) free human life and subjectivity, by making us identify with the images that are presentd to us, and renounce of lived reality and “life lived in the first person” (Jappe). Adorno writes, following in the footsteps of Marx’s critique of commodity fetishism, that they “[obscure] the real alienation between people and beteween people and things” and “[become] a substitute for a social immediacy that is being denied to people” (‘Prologue to Television’ [1953], cited by Jappe).

Let’s now briefly outline the meaning and central concepts of the culture industry and the spectacle. Contrary to a lazy and disingenuous assumption, Adorno and Horkheimer’s “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception” – and Adorno’s broader analysis and critique about the culture industry (both before and after he published Dialectic of Enlightenment with Horkheimer in 1947) – isn’t conservative or elitist, although I’m obviously not gonna defend Adorno’s infamous dismissal of jazz (yes he was a weirdo in some ways):

it is not universal accessibility that is the target of critique, but the fact that the culture industry, as they say, “constitute[s] the most sensitive instrument of social control”. It is therefore the structurally alienated and objectively authoritarian content of capitalist mass culture rather than its accessibility to those outside of elite groups that is at issue here. This content, according to Adorno and Horkheimer, is “aesthetic barbarity”, because “the morality of mass culture is the cheap form of yesterday’s children’s books” for the purpose of making increasingly more infantilized individuals available for social degradation.

Robert Kurz: The culture industry in the 21st century

Adorno started constructing his critique of the culture industry in the late 1930s and early 1940s through his work on “popular music”, where he already formulated the two core concepts that would define his argument: “standardization” and “plugging”. Standardization refers to the factory-like large-scale method of production where cultural commodities get produced according to a formal predefined model, leading to cultural products characterised by uniformity, repetition and stereotyping. This is of course why Adorno and Horkheimer call contemporary cultural production the “culture industry”, since they produce mass-produced cultural commodities that like all commodities rely on the economic abstraction of use-value – in favor of exchange-value, and ultimately money and capital. The second concept – plugging, perhaps better understood as matraquage in the French translation (basically meaning beating sb with a “matraque” or club) – is just as important and the necessary complement to standardization. It refers to the endlesss and mindless repetition of cultural products/materials – initially Adorno was talking about musical titles – which are plugged or hammered into people’s heads to the point the point that they start fascinating over them. Adorno wrote about it in “On Popular Music”:

The structure of the musical material requires a technique of its own by which it is enforced. This process may be roughly defined as “plugging.” The term “plugging” originally had the narrow meaning of ceaseless repetition of one particular hit in order to make it “successful.” We here use it in the broad sense, to signify a continuation of the inherent processes of composition and arrangement of the musical material. Plugging aims to break down the resistance to the musically ever-equal or identical by, as it were, closing the avenues of escape from the ever-equal. It leads the listener to become enraptured with the inescapable. And thus it leads to the institutionalization and standardization of listening habits themselves. Listeners become so accustomed to the recurrence of the same things that they react automatically. The standardization of the material requires a plugging mechanism from outside, since everything equals everything else to such an extent that the emphasis on presentation which is provided by plugging must substitute for the lack of genuine individuality in the material. The listener of normal musical intelligence who hears the Kundry motif of Parsifal for the first time is likely to recognize it when it is played again because it is unmistakable and not exchangeable for anything else. If the same listener were confronted with an average song-hit, he would not be able to distinguish it from any other unless it were repeated so often that he would be forced to remember it. Repetition gives a psychological importance which it could otherwise never have. Thus plugging is the inevitable complement of standardization.C

Provided the material fulfills certain minimum requirements, any given song can be plugged and made a success, if there is adequate tie-up [sic] between publishing houses, name bands, radio and moving pictures. Most important is the following requirement: to be plugged, a song hit must have at least one feature by which it can be distinguished from any other, and yet possess the complete conventionality and triviality of all others.

Theodor Adorno (1941) On Popular Music [With the assistance of George Simpson]. In Essays on Music, edited by Richard Leppert, University of California Press, p. 447. [Copy of this text online]

Through this endless and deafening repetition, people can begin enjoying them (in an alienated way, of course) as somehow unique cultural creations despite the fact that they were mass-produced in an assembly-line-like, anti-creative fashion. This plugging creates an artificial, pseudo-individuality in consumption/enjoyment of cultural products, despite the lack of individuality in their creation. As Pierre Arnoux writes, this contributes to creating “a collective psychology for which the real is the necessary to which we can do nothing but submit”.

Alexander Neumann describes the core of the political implications of Adorno’s (and everyone who took up his critique) critique:

Resistance to the culture industry is resistance to its general stereotyping, which seeks to crush all singular and particular experiences.

The stereotype of mass production, from cars to films, which does not question usage and shared meaning. The stereotypical nature of new industries that renew techniques and media, but never forms or creation.

Stereotypical modes of socialisation that encourage submission to authority, in the family, at school and in the workplace, or else outsiders will be relegated.

Stereotyping of the information, messages and opinions that are prefabricated by the mass media for audiences conceived as consumers, conceived as credulous, if not idiotic, receptors who must not act on their own despite the proclaimed democratic discourse. Stereotyping of the rigid, conventional aesthetic forms through which the culture industry expresses itself, in order to perfect the correlation between injunctions and standardised proposals, in TV films that do nothing more than repeat the daily frustration of viewers seeking to escape it through entertainment.

Stereotypical absorption of new, deviant or counter-cultural forms, stunned by the principle of similarity, and all returning to the same pattern.

[This is a rough translation from the French]

Anselm Jappe and Tom Bunyard (see the list at the end) have helped us save the radical contribution of Guy Debord from his many misinterpreters and the recuperation-and-distortion of his ideas – along with the 1960s’ optimism for creativity, autonomy, and imagination – by mainstream society and the Left hand of capital through the very processes that he had talked about.

Debord’s theory-as-critique of the spectacle has often been wrongly reduced to a cryptic and overly high-brow critique of consumerist mass media, but this is evidently the result of not reading or misunderstanding his own definition; granted, to be able to grasp it you have to be somewhat familiar with the style and conceptual abstraction/method of Hegelian-Marxian theory. Please let me indulge in some classic Debordian prose from Society of the Spectacle, which simultaneously defines the spectacle and adresses some of its main superficial/particular ‘manifestations’ which are indeed rooted in modern mass media (and the culture industry!):

3. The spectacle presents itself simultaneously as all of society, as part of society, and as a means of unification. As a part of society, it is ostensibly the focal point of all vision and all consciousness. But due to the very fact that this sector is separate, it is in reality the domain of delusion and false consciousness: the unification it achieves is nothing but an official language of universal separation.

4. The spectacle is not a collection of images; it is a social relation between people that is mediated by images.

5. The spectacle cannot be understood as a mere visual excess produced by mass-media technologies. It is a worldview [Weltanschauung] that has actually been materialized, that has become an objective reality.

6. Understood in its totality, the spectacle is both the result and the project of the present mode of production. It is not a mere supplement or decoration added to the real world, it is the heart of this real society’s unrealism. In all of its particular manifestations – news, propaganda, advertising, entertainment – the spectacle is the model of the prevailing way of life. It is the omnipresent affirmation of the choices that have already been made in production and in the consumption implied by that production. In both form and content the spectacle serves as a total justification of the conditions and goals of the existing system. The spectacle is also the constant presence of this justification since it monopolizes the majority of the time spent outside the modern production process.

7. Separation is itself an integral part of the unity of this world, of a global social praxis split into reality and image. The social practice confronted by an autonomous spectacle is at the same time the real totality which contains that spectacle. But the split within this totality mutilates it to the point that the spectacle seems to be its goal. The language of the spectacle consists of signs of the dominant system of production-signs which are at the same time the ultimate end-products of that system.

8. The spectacle cannot be abstractly contrasted to concrete social activity. Each side of such a duality is itself divided. The spectacle that falsifies reality is nevertheless a real product of that reality, while lived reality is materially invaded by the contemplation of the spectacle and ends up absorbing it and aligning itself with it. Objective reality is present on both sides. Each of these seemingly fixed concepts has no other basis than its transformation into its opposite: reality emerges within the spectacle, and the spectacle is real. This reciprocal alienation is the essence and support of the existing society.

10. The concept of “the spectacle” interrelates and explains a wide range of seemingly unconnected phenomena. The apparent diversities and contrasts of these phenomena stem from the social organization of appearances, whose essential nature must itself be recognized. Considered in its own terms, the spectacle is an affirmation of appearances and an identification of all human social life with appearances. But a critique that grasps the spectacle’s essential character reveals it to be a visible negation of life – a negation that has taken on a visible form.

11. In order to describe the spectacle, its formation, its functions, and the forces that work against it, it is necessary to make some artificial distinctions. In analyzing the spectacle we are obliged to a certain extent to use the spectacle’s own language, in the sense that we have to operate on the methodological terrain of the society that expresses itself in the spectacle. For the spectacle is both the meaning and the agenda of our particular socio-economic formation. It is the historical moment in which we are caught.

24. The spectacle is the ruling order’s nonstop discourse about itself, its never-ending monologue of self-praise, its self-portrait at the stage of totalitarian domination of all aspects of life. The fetishistic appearance of pure objectivity in spectacular relations conceals their true character as relations between people and between classes: a second Nature, with its own inescapable laws, seems to dominate our environment. But the spectacle is not the inevitable consequence of some supposedly natural technological development. On the contrary, the society of the spectacle is a form that chooses its own technological content. If the spectacle, considered in the limited sense of the “mass media” that are its most glaring superficial manifestation, seems to be invading society in the form of a mere technical apparatus, it should be understood that this apparatus is in no way neutral and that it has been developed in accordance with the spectacle’s internal dynamics. If the social needs of the age in which such technologies are developed can be met only through their mediation, if the administration of this society and all contact between people has become totally dependent on these means of instantaneous communication, it is because this “communication” is essentially unilateral. The concentration of these media thus amounts to concentrating in the hands of the administrators of the existing system the means that enable them to carry on this particular form of administration. The social separation reflected in the spectacle is inseparable from the modern state – that product of the social division of labor that is both the chief instrument of class rule and the concentrated expression of all social divisions.

As Bunyard helpfully summarizes, in what is perhaps the best single definition of the spectacle (although it’s still a full paragraph lol):

At root, Debord’s spectacle denotes a condition of fetishistic separation from bodies of individual and collective power: a separation that ultimately amounts, as we will see below, to a condition in which human subjects become detached from their capacities to shape their own lived time. As this entails a relation between a passive, spellbound subject and an active, seemingly independent object, it certainly relates to the role played by imagery and entertainment within modern society: their profusion was in fact held to reflect the sense in which modern capitalism had brought that dynamic of contemplative separation to such an extreme that it had become expressed in full, self-evident view across the surface of a society that it had moulded to the very core. Yet it remains the case that that inner dynamic constitutes the real heart of the concept, and that it by no means pertains solely to the media and the visual. Ultimately, The Society of the Spectacle describes a society that has come to be characterised by its separation from its own history, as a result of abdicating its capacity to shape its future to a sovereign economy.

The spectacle as such is not what could be described, following that common misconception, as the “circus” of the media and modern entertainment/culture industry. At the same time, it obviously does contain and refer in part to the latter, but as Debord and Bunyard clearly emphasize, these are particular manifestations rather than the phenomenon itself. As Sergio C. Fanjul (based on Jappe’s work) writes (btw this is the starting point of Situationists as a whole):

The “spectacle” encompasses more than just media power, the ubiquity of social media or talk show sensationalism. It’s a broader concept that refers to people passively observing others who make decisions that affect their own lives. This occurs not only in consumerism, where material possessions replace real experiences, but also in politics, religion and art, where representation replaces a lived reality. (…) Debord described a society where people lived disconnected from their own lives, mere spectators rather than active participants in a commercialized world. It was a life that lacked authenticity and needed to be challenged.

Concluding this summary of what Debord’s concept and critique of the spectacle, let me quote Jappe again because I think this really helps understanding the specific analysis of contemporary alienation that Debord contributed to:

In this, the supreme form of alienation, real life is increasingly deprived of quality and broken up into activities that are fragmentary and separated from one another, while images of that life become detached from it and form an ensemble. This ensemble of images – the spectacle in a narrower sense – takes on a life of its own. As in the case of religion, activities and possibilities appear as separate from the individuals or the society that actually engender them; in the spectacle, however, they appear to be not in heaven but on earth. Individuals find themselves cut off from everything of concern to them, their only contact therewith mediated by images chosen by others and distorted by interests other than theirs.

Anselm Jappe in the SAGE Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory (see reading list)

It’s also worth noting that Siegfried Kracauer’s pioneering work in the 1920s and 1930s remarkably anticipated Debord’s argument:

[Society] consciously – or even more, no doubt, unconsciously – sees to it that this demand for cultural needs does not lead to reflection on the roots of real culture, hence to criticism of the conditions underpinning its own power. Society does not stop the urge to live amid glamour and distraction, but encourages it wherever and however it can. (…) Society by no means drives the system of its own life to the decisive point, but on the contrary avoids decision and prefers the charms of life to its reality, Society too is dependent upon diversions, Since it sets the tone, it finds it all the easier to maintain employees in the belief that a life of distraction is at the same time a higher one, It posits itself as [the supreme value/truth] and, if the bulk of its dependants take it as a model, they are already almost where it wants them to be.

Siegfried Kracauer (1929) The Salaried Masses: Duty and Distraction in Weimar Germany (Verso, 1998)

We can now come back to the general theme of my investigation, namely propaganda, disinformation and media ecology. The Frankfurt School and adjacent figures like Kracauer actually did a lot of very valuable research/analysis on propaganda (including fascist/Nazi propaganda). But here I’m focused on the culture industry and the spectacle as major sectors in the ideological, cultural and political socialization of modern individuals and groups.

Both approaches/concepts argue/imply that concrete ideological agendas and manipulation take the backseat to the insidious normative/cultural reinforcement of the status quo that the culture industry and the spectacle fundamentally consist in:

According to Debord, the spectacle as ‘ideology in material form’ has replaced all specific ideologies (SS §213); according to Horkheimer and Adorno, social power is much more effectively expressed by means of the seemingly non-ideological culture industry than by means of ‘stale ideologies’ (DE, 136).

Anselm Jappe in the SAGE Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory (see reading list)

Again, Debord specifically says that “in all its particular manifestations – news, propaganda, advertising, entertainment – the spectacle is the model of the prevailing way of life”, its “omnipresent affirmation” and “total justification” (§6, see also §24 that I quoted above). He defines “mass media” as the spectacle’s “most glaring superficial manifestation” (§24), which tells us that he did think all this modern media/entertainment/propaganda/advertising ecosystem had a central function and role in shaping the general population’s worldview/perceptions, but that this was first and foremost about the global spectacular dynamic wherein people “are now passive observers of an objective world that is composed and conducted by their own alienated activity“ (Bunyard, Debord, Time and Spectacle, p. 19) rather than any specific ideological socializations and politicizations.

Likewise, Pierre Arnoux explains that for Adorno propaganda “appears to be a surface phenomenon, relying on the psychic structure consolidated by the culture industry” and “despite its own intentions, achieves the same result – the confirmation of the existing state of things.” Propaganda “only acts punctually and locally, whereas mass culture is omnipresent and works on the psychological underpinning on which it is based”.

Interestingly, after WWII – when the topic of the mass manipulation of public opinion was being debated across the West – Kracauer pushed back against the widespread tendency (to this day) to think that propaganda can comprehensively manipulate and control people’s worldviews/beliefs/minds/opinions. Even in the case of Nazi Germany, he rejects the assumption that Hitler was merely manipulating a passive population that was totally brainwashed and unthinking; rather as summarized by Stéphanie Baumann:

The mass’s relationship with the Führer develops more along the lines of a consensual staging of power, based as much on identification as on internalization. Once the mechanisms are in place, the masses become self-hypnotized as soon as the slightest key propaganda signal is brandished.

As far as I’m concerned, it’s necessary to combine both Adorno’s and Debord’s emphasis on the underlying “false form of social cohesion [and] unacknowledged ideology designed to create consensus” – by critiquing the spectacle and the culture industry – and the more granular sociopolitical analysis that I’ve constructed in this project/study. Adorno and Debord, as well as other authors I’ve not yet explored/studied, contributed greatly to the radical critique of the cultural and fetishistic dynamics of bourgeois modernity. But it’s also important to analyze, understand and critique even the “superficial” manifestations of modern culture and how they impact socializations and politicizations beyond the – undeniable – function of repeating and reinforcing the submission to and false consciousness about the existing order and social relations.

On top of that, there’s simply a political necessity to monitor, document and explain the various forces and actors trying to gain power, impose their agendas and ideologies, manipulate the public, and so on. In conclusion, though the big picture offered by the critical framework inherited from Adorno, Debord and others is fundamental, we should both continue developing and refining this critique, and also complement it by a more straightforward and less abstract analysis of political dynamics, struggles, influence, strategies, violence, etc. These are ultimately different levels of analysis/abstraction, which are both crucial and were indeed analyzed by the Frankfurt School who didn’t only produce meta-theoretical critiques but also produced a lot of empirical research and sociopolitical analysis – on propaganda, authoritarianism, popular culture and fascism – that shows both levels aren’t mutually exclusive but rather complementary.

Bibliography

- Anselm Jappe (2018) The Spectacle and the Culture Industry, the Transcendence of Art and the Autonomy of Art: Some Parallels between Theodor Adorno’s and Guy Debord’s Critical Concepts. In Beverley Best, Werner Bonefeld, Chris O’Kane (editors) The SAGE Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Pierre-François Noppen & Gérard Raulet (dir.) (2020) Théorie critique de la propagande. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme. doi :10.4000/books.editionsmsh.25009

- Ian Aitken (2022) Cinematic Realism: Lukács, Kracauer and Theories of the Filmic Real. Edinburgh University Press.

- Harry T. Craver (2017) Reluctant Skeptic: Siegfried Kracauer and the Crises of Weimar Culture. Berghahn Books.

- Tara Forrest (2015) The Politics of Imagination: Benjamin, Kracauer, Kluge. Transcript Verlag.

- Miriam Hansen (2012) Cinema and Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor W. Adorno. University of California Press.

Adorno & the Culture Industry

- Alexander Neumann (2018) Kulturindustrie : l’industrie de la culture en tant que modèle critique. Variations [En ligne], 21 | 2018.

- Theodor Adorno & Max Horkheimer (1947) The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception. Dialectic of Enlightenment; trans. Edmund Jephcott, Stanford University Press, 2002, pp 94-136, n268-272.

- Theodor Adorno (1964) L’industrie culturelle. Communications, 3, p. 12-18. DOI : 10.3406/comm.1964.993

- Theodor Adorno (1941) On Popular Music [With the Assistance of George Simpson]. In Essays on Music, edited by Richard Leppert, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2002.

- Theodor Adorno (1954) Television and the patterns of mass culture. Quarterly of film, radio and television, n°8, 213-35. Published in Bernard Rosenberg, David Manning White (editors), Mass Culture: The Popular Arts in America. The Free Press, 1963.

- Theodor Adorno (1938) On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening. In Arato, Andrew, and Eike Gebhardt (editors) The Essential Frankfurt School Reader. New York: Continuum, 1982.

- Aidin Keikhaee (2019) Adorno, Marx, dialectic. Philosophy & Social Criticism, doi: 10.1177/0191453719866234.

- Robert Kurz (2010) The culture industry in the 21st century. Talk given in Sao Paulo on November 21 2010.

- Christian Lotz (2018) The Culture Industry. In Beverley Best, Werner Bonefeld, Chris O’Kane (editors) The SAGE Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Ernst Bloch

- Lucien Pelletier (2020) Militantisme, propagande et métaphysique : Pour introduire à la « Critique de la propagande » d’Ernst Bloch. In Noppen, P., & Raulet, G. (Eds.), Théorie critique de la propagande. Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme. doi :10.4000/books.editionsmsh.25119.

- Ernst Bloch (1937) Critique de la propagande. In Noppen, P., & Raulet, G. (Eds.), Théorie critique de la propagande. Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme. doi :10.4000/books.editionsmsh.25124, 2020.

Siegfried Kracauer

- Siegfried Kracauer (1960) Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality, Oxford University Press, 1960, PDF; new ed., intro. Miriam Bratu Hansen, Princeton University Press, 1997.

- Siegfried Kracauer (1947) From Caligary to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, Princeton University Press, 1947; rev.ed., exp., ed. & intro. Leonardo Quaresima, Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Siegfried Kracauer (1927) The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, trans, ed. & intro. Thomas Y. Levin, Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Siegfried Kracauer (author), Johannes von Moltke (editor) (2012) Siegfried Kracauer’s American Writings: Essays on Film and Popular Culture. University of California Press.

- Siegfried Kracauer (author), John Abromeit, Jaeho Kang, Graeme Gilloch (editors) (2022) Selected Writings on Media, Propaganda, and Political Communication. Columbia University Press.

- Daniel Sullivan (2023) Toward a Reevaluation of Siegfried Kracauer and the Frankfurt School. Triple C: Journal for a Global Sustainable Transformation Society, 21:1.

Stuart Hall and Cultural Studies

- Stuart Hall (author), Morley David (editor) (2019) Essential essays Volume 1, Foundations of cultural studies. Duke University Press.

- Stuart Hall (author) & Paddy Whannel (editor) (2018) The Popular Arts. Duke University Press.

- Stuart Hall (author) & Charlotte Brunsdon (editor) (2021) Writings on Media: History of the Present. Duke University Press.

- Stuart Hall (author), Jennifer Daryl Slack, Lawrence Grossberg (editors) (2016) Cultural Studies 1983: A Theoretical History. Duke University Press.

Raymond Williams

- Paul Stasi (editor) (2021) Raymond Williams at 100. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Guy Debort, the Situationists and the Spectacle

- Guy Debord (1967) La Société du Spectacle. Initial text in French and all translations: https://monoskop.org/log/?p=299. Kenn Knabbb’s annotated translation: PDF, online version (ENG).

- Guy Debord (1988) Commentaires sur la société du spectacle, Paris: Lebovici, new ed. as Commentaires sur la société du spectacle, suivi de Préface à la quatrième édition italienne de ‘La Société du Spectacle’, Paris: Gallimard, 1992; repr., 1996. English: Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, trans. Malcolm Imrie, London: Verso, 1990.

- Debord’s Films:

- Critique de la séparation [Critique of Separation], 35mm, B&W, 1961, 19 min. Script (en).

- La Société du spectacle [The Society of the Spectacle], 35mm, B&W, 1973, 90 min. Part 2. Script (en).

- Réfutation de tous les jugements, tant élogieux qu’hostiles, qui ont été jusqu’ici portés sur le film « La Société du spectacle [Refutation of All the Judgements, Pro or Con, Thus Far Rendered on the Film “The Society of the Spectacle”], 35mm, B&W, 1975, 20 min. Script (en).

- Bureau of Public Secrets: Guy Debord’s Films (in English).

- Anselm Jappe (2001) Guy Debord. Denoël; English translation

- Anselm Jappe (2004) L’avant-garde inacceptable: Réflexions sur Guy Debord. Éditions Lignes & Manifestes.

- Tom Bunyard (2017) Debord, Time And Spectacle: Hegelian Marxism And Situationist Theory. Brill, Historical Materialism Book Series.

- Tom Bunyard (2014) History is the Spectre Haunting Modern Society”: Temporality and Praxis in Guy Debord’s Hegelian Marxism. Parrhesia, n°20, 62-86.

- Ken Knabb (editor and translator) (2006 [1981]) Situationist International Anthology. Revised and expanded edition, Bureau of Public Secrets. Online version (with links to each text): https://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/.

- Johannes von Moltke (2018) Cinema – Spectacle – Modernity. In Beverley Best, Werner Bonefeld, Chris O’Kane (editors) The SAGE Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Benoît Bohy-Bunel (2019) Symptômes contemporains du capitalisme spectaculaire. Actualités inactuelles. Paris, L’Harmattan.

- New Institute for Social Research: Reading The Society of the Spectacle: A Reconstruction of Debord’s Revolutionary Theory of Time.

Oskar Negt & Alexander Kluge

- Oskar Negt & Alexander Kluge (1990 [1971]) La télévision publique. De la publicité bourgeoise à la technique concrète. Réseaux, vol. 9: n°44-45, 243-269. Traduction par Michael Derrer et Jean-Yves Pidoux du chapitre “Das öffentlich-rechtliche Fernsehen – in konkreter Technik umgesetzte bürgerliche Öffentlichkeit” dans Öffentlichkeit und Erfahrung.

Walter Benjamin & Bertol Brecht

- Walter Benjamin (1935) The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, eds. Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty and Thomas Y. Levin, trans. Edmund Jephcott, et al., Cambridge/London: The Belknap Press, 2008.

- Walter Benjamin (1966) Understanding Brecht, London/New York: Verso, 1998.

- Roswitha Mueller (1989) Bertolt Brecht and the Theory of Media. University of Nebraska Press.

- Stephen Parker (2014) Bertolt Brecht: A Literary Life. Bloomsbury Methuen Drama.

György Lukács

- György Lukács (1920) The Theory of the Novel: A Historico-Philosophical Essay on the Forms of Great Epic Literature, trans. Anna Bostock, London: Merlin, 1962; MIT Press, 1971.