The starting point of this brief historical investigation is a strong rejection of the post-WWII self-description and performativity of Europe and the West as leading and representing a so-called “liberal” – and “democratic”, “rational”, “progressive”, “rules-based/law-abiding”, “rights-based”, “postcolonial”, “post-fascist”, etc – global order that supposedly opposes all authoritarianism, chauvinisms and ethnonationalisms, racisms, and ‘human-rights violations’ and atrocities/war crimes/genocides. I don’t think I need to remind readers how deeply questionable all of these descriptions are, what I find more interesting is focusing on some of the historical processes that got us here. To be more precise, I’m focusing on the 20th century (esp. from the interwar period onward) but it goes without saying that this all was itself grounded in the longer history of colonialism, capitalism, and more.

Europe’s self-image – as well as the rhetoric of liberal international institutions like the United Nations – since WWII has been constantly/obsessively defined in contrast to 30s/40s Nazism/fascism (and ‘High Stalinism’), despite never abandoning two of its main premises/goals: ethnonationalism/nation-states and a unified European empire. Moreover, contrary to its rhetoric/delusions, the postwar liberal order (like all liberal orders) was not only not incompatible with far-right, reactionary, authoritarian, or ‘archaic’ elements, but inherently tied to them (although obviously in changing, sometimes supportive, sometimes antagonistic, ways). This is explained in this great paper by Alexander Anievas and Richard Saull:

Viewed from a longue durée perspective, we can identify not only the connections between the far-right and the Cold War liberal order but also the structural continuities that define the ontology of liberalism as a political order. Liberal orders—from the nineteenth century to contemporary times—have maintained an ambivalent relationship to the politics and ideas of the far-right. Such ambivalences—that at certain moments become embraces—derive from the structural properties of liberal order.

The first is the recurrent phenomena produced from the destabilizing “geosocial” consequences of the uneven and combined nature of capitalist development and how this shapes the ideopolitical conditions for liberal international order construction. The “social reality” of uneven development challenges liberal assumptions about the complementarity of politics and economics. For the spatial expansion and reproduction of capitalism takes place across and within developmentally differentiated locales often defined by the presence of significant nonliberal political conditions. This combined nature of capitalist development means that the universalizing pretensions of liberal internationalism (individual freedom, constitutional order, and representative government as the ideal-typical political framing for the market economy) tend to come up against concrete social conditions that problematize such an arrangement.

It is because of the uneven and combined character of capitalist development that the ideopolitical forces of the far-right can be seen as organic to and constitutive of liberal orderings. Emerging within the global crucible of capitalist development,the far-right articulates a distinct political response to the social instabilities and crises engendered by it: a politics defined by articulating a mythical presentation of the past that idealizes it in racial and cultural terms thereby continuously reproducing the past in the present— a contradictory amalgam of “archaic” and “contemporary” forms (Trotsky 1977). As such, there remains the ever-present possibility (…) that far-right forces gain political support in contexts of major crises. This was how attempts at liberal international order construction played out under the aegis of British hegemony and how its combined character contributed to the resultant crises within it, culminating in the First World War.

The relevance of this point for explaining both the construction and political characteristics of the post-1945 international order is that these contradictions— which had driven the world to war again in 1939—remained, to a significant degree,in place after the military defeat of fascist states. Thus, in the former fascist states of Germany, Italy, and Japan, the social-political conditions for constructing the bases of liberal orders were problematized because of the continuing political legacies of their uneven and combined development, which the war had reconstituted rather than resolved. Yet, by this time, the primary ideopolitical challenge came from are vitalized radical left. The crises and conflicts that defined the interwar period, and which fatally undermined attempts to reconstruct a liberal international order, had not immediately dissipated. Instead, the challenge that now confronted US political strategists was the problem of constructing a liberal international order out of social and political conditions in some of its key geopolitical zones that were antagonistic to the very principles of said order. This was the primary dilemma faced by US policymakers after the war: the recurring problem of reconstructing and managing the contradictory dynamics of an international liberal order wherein its constituent parts were hardly conducive to it.

In moments of crisis, then, the political bases of liberal orders have often relied upon far-right mobilizations to help secure them as far-right ideologies provide an important ideopolitical imaginary to compensate for the intense dislocations and sense of anomie characterizing such conjunctures. In this respect, the structural dynamics of capitalist development generate far-right forces as a kind of coercive “reserve army” that politicians and ruling class forces can draw on in times of crisis but can never fully control. This is not to suggest that far-right actors should be regarded as pawns of ruling class interests, parroting the crude Stalinist thesis on fascism, or that the far-right is functional to reproducing liberal (international) orders. Rather, it is to recognize the political role played by far-right forces in helping thwart revolutionary challenges to liberal-capitalist orders, including the authoritarian and antidemocratic elements within the “deep” state that tend to appear when the social regime of capital is most vulnerable. The far-right can do this by offering an alternative ideological legitimation of capitalist social orderings from that of liberalism. Some understanding of the architectonics of the liberal state, its terms of order,and the strategic place of the far-right in its contradictory reproduction is therefore crucial.

In the ruins and graveyards that remained in Europe once WWII came to an end, instead of destroying the structures of bourgeois-colonial modernity that had led directly to this carnage and to fascism as such, the West reasserted both its colonial/imperial hegemony (despite the wave of formal decolonizations) and the supremacy of the nation-state as the prevailing mode of political-territorial organization (this was already Alan Milward’s argument in The European Rescue of the Nation-State, more than twenty years ago).

“All the elements of a solution to the great problems of humanity have, at different times, existed in European thought. But Europeans have not carried out in practice the mission which fell to them, which consisted of bringing their whole weight to bear violently upon these elements, of modifying their arrangement and their nature, of changing them and, finally, of bringing the problem of mankind to an infinitely higher plane.” (Fanon)

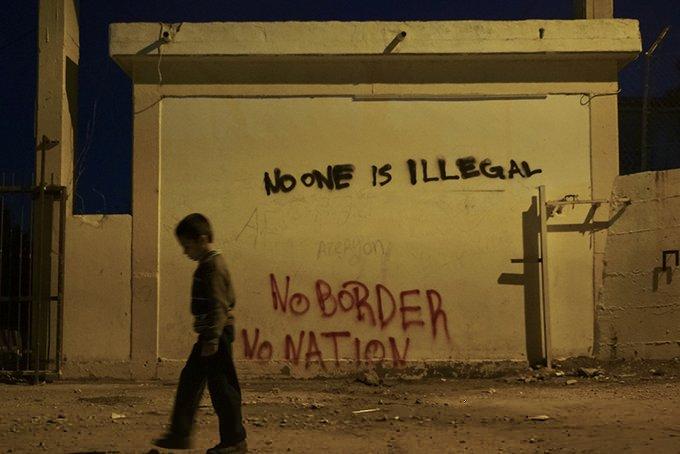

Although the past centuries of state formation, capitalism and colonialism had already contributed to this, the global restructuring of power, politics and capitalism from the WWI to the late 1970s – with the fall of various empires (Ottomans, Austro-Hungary, Japan…) and the formal end of European colonial rule in Africa and Asia – spawned hundreds of new nation-states, replicating the murderous and reactionary European model that had led to the deaths – from war, genocide and more – of millions (and the displacement, material deprivation, torture, etc. of even more people). The UN was created in 1945 to deal with the unprecedented destruction, displacements and other crises tied to WWII, as well as the redistribution of power, borders, spheres of influences etc. between the Allies (i.e. British, American, French, and Soviet empires), and of course the question of how to restart Europe’s damaged capitalist economies. Despite some humanitarian rhetoric and declarations, its mission clearly wasn’t to build a different more egalitarian world order based on ending colonialism, ethnonationalisms, genocides, geopolitical rivalries, and modern warfare. It’s precisely in the opposite direction that both the UN and the so-called “liberal world order” (or as Nandita Sharma more accurately calls it, the “Postcolonial New World Order”) went from 1945 onwards:

In the early twenty-first century (…) it became tempting to look back to 1945 and the war against Hitler as a kind of Golden Age in which the far-sighted architects of a new and mutually beneficial world order learned the lessons of the Nazi New Order and resolved to revive liberalism on a new basis. As history this is questionable. Human rights talk in the 1940s was mostly just that, and took a long time to become politically influential – perhaps not until the 1970s. Its function in 1945 was to allow the burial of the old minority rights system, clearing the way for a globalization of the ethnically purified model of the nation state which the Nazis had done more than anyone to push through. (…) as the global extension of [this model] produced wave after wave of refugees, what emerged in the rebuilt international institutions around the United Nations was an entirely new regime of refugee protection. (…) [The latter] was not intended to confront a permanent large-scale phenomenon but rather to ease the plight of the very specific populations stranded or evicted during and immediately after the war itself.

Mark Mazower (2008) Hitler’s Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe. The Penguin Press, New York, p. 602-603. For Nazis’ conception of Europe and their ‘New Order’, see chap. 17.

Mazower identifies the central pillars of the nation-state (which implies ethnonationalism by definition) as the “struggle for land” and the “problem of minorities”, both of which imply constant border, racist, xenophobic, etc violence and state/military/police/militia/paramilitary-enforced expulsions and deportations (we could add a lot more, e.g. gender-based and anti-Indigenous violence). This is why despite all the life-saving aid and work that some UN agencies do, the UN model itself is fundamentally rotten because it founded on the same framework as not only Western states and empires, but Nazism itself.

Nazism aimed to renew Germany’s strength by creating a classless, racially pure community in which there would be no minorities. Later, it offered ethnic purification as the solution for regional instability in eastern Europe as well. In Hitler’s speech of 6 October 1939, he had talked about adjusting ‘the disposition of the entire living space according to the various nationalities, that is to say, the solution of the problems affecting the minorities’. The Nazis did not invent this approach, which had first emerged in the Balkans. It also continued after them, and more people were expelled from eastern Europe between 1945 and 1949 than during the war itself. With decolonization, the ideal of the nation-state was exported overseas (…) But this simply globalized the struggle for land and the problem of minorities as well.

Mark Mazower (2008) Hitler’s Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe. The Penguin Press, New York, p. 597.

Indeed, as you probably know, two of the most crucial events in world history that followed the end of WWII – and in which Western powers and the UN played major roles – was the creation of Israel // the Nakba, and the partition of India and Pakistan which also included the massacre, rape, torture, forced displacement, immiseration and migration of millions of people. Both events demonstrated the disastrous consequences of replicating the ethnonationalist framework, after half a century of countless colonial and ethnonationalist genocides from Armenia and Namibia to Auschwitz (for more, see the literature – especially Nandita Sharma’s book Home Rule – included at the end).

Zionism and the Nakba epitomized – and still epitomizes today – the unforgivable horror launched on innocent lives by the continuation of Western-inspired colonialism, statism and ethnonationalism. In fact, as many people have highlighted, “Zionism had been a European national movement from the start” (Mazower, p. 597), so much so that racist and colonialist German theorists/intellectuals were one of the key influences in Israel’s strategy for colonising and settling Palestine:

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the German influence on Israeli settlement strategy remained strong after independence. In few countries after the war, for instance, was spatial planning as important as it was in the new Jewish state, and the first Israeli national plans for population distribution were strongly influenced by the interwar German school of economic geography, especially by the ideas of Walter Christaller, whose theories about the optimal location of settlements had been deployed in Himmler’s colonization of wartime Poland and in General Plan East.

(…) In Palestine itself, Zionist leaders were concerned not only to help the survivors of the genocide but to assess their potential for assisting the national cause and their representatives visited many of the camps of Jewish Displaced Persons. David Ben Gurion, the leader of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, was dismayed by the inmates’ state of mind – their factionalism, selfishness and incessant demands – and he anticipated great difficulty teaching them how to become ‘citizens of the Jewish state’. Even so, in March 1945 he reckoned on a million Jews arriving over the following year and a half in order to push the British into a more pro-Zionist stance. The figures were much too ambitious. When the British upheld immigration restrictions instead and turned back Mossad ships carrying illegal immigrants, Ben Gurion compared their policy with that of the Nazis. But in fact only a small proportion of the survivors actually wanted to go to the Middle East at all, and there were no more than 220,000 in Palestine when the 1948 war broke out.

As Ben Gurion understood very well, Israel’s emergence – while intimately connected to the experience of the war – depended much less on the influx of survivors from Europe than it did on the political impact of the Holocaust and on American backing in particular. In the massive immigration wave of the first years of the new state, the crucial source of youthful arrivals was not eastern Europe (migrants from there tended to be older) but the Middle East and North Africa. Europe’s Jewish population started to grow again after 1950, but that in the Arab lands did not. In short, the central European practice of ethnic homogenization was spreading – and being spread – to the Arab lands as well. The motor was Israel’s single-minded pursuit of an organized, state-led ‘homecoming’ which saw the existence of Jews abroad as a source of national weakness and their ‘return’ as essential for national survival (another way perhaps in which the influence of German nationalism continued to exert itself).

Mark Mazower (2008) Hitler’s Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe. The Penguin Press, New York, p. 599-601.

‘Eurafrica’: The Colonial Origins and Present of European Integration

Where did this postwar renewed imperial consensus in the shape/form of a unified Europe come from? A decade ago, Swedish historians Peo Hansen and Stefán Jónsson shone light on the colonial origins of European integration, emphasizing that ‘the general idea of an internationalization and supranationalization of colonialism in Africa was one of the least controversial and most popular foreign policy ideas of the interwar period’. Indeed, everyone from fascists – e.g. Vichy France, the Third Reich’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of the Economy, Mussolini, Ernesto Massi, Otto Strasser, Oswald Mosley, Francis Parker Yockey, South African apartheid fascist Oswald Pirow, Gaston-Armand Amaudruz (Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 67-70; Bassin 2023 cited at the end) – to Central European nationalists and liberals like Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi (see Thorpe 2018), to France’s Gaullists like François Mitterand (and other French socialists), shared this idea.

Regarding Hitler himself, while in Mein Kampf he’d opposed the idea of extra-European German colonies and Eurafrica (which he associated with Coudenhove-Kalergi, a favorite scapegoat of him and as fascists to this day), in a conversation in October 1941 he effectively supported it (note: this is a paraphrase from a conversation with him, rather than a written text or speech…):

Noteworthy in the fighting in the east was the fact that for the first time a feeling of European solidarity had developed. This was of great importance especially for the future. A later generation would have to cope with the problem of Europe – America. It would no longer be a matter of Germany or England, of Fascism, of National Socialism, or antagonistic systems, but of the common interests of Pan – Europe within the European economic area with her African supplements. The feeling of European solidarity, which at the moment was distinctly tangible, even though only faint against the background of the fighting in the east, would gradually have to change generally into a great recognition of the European community. (…) the future did not belong to the ridiculously half-civilized America, but to the newly arisen Europe that would also definitely prevail with her people, her economy, and her intellectual and cultural values, on condition that the East were placed in the service of the European idea and did not work against Europe.

Record of the conversation between the Führer and Count Ciano at headquarters on October 25, 1941. Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945, from the Archives of the German Foreign Ministry, p. 692.

And most significantly, the European Union’s founders themselves adhered to this notion/conception. I’ll refer you to the Hansen and Jónsson’s work for more details, but Hansen summarizes it as follows:

The EU’s founders stressed the Community’s huge extra-European scope and natural sphere of influence, which was designated as “Eurafrica” and codified in the Rome Treaty’s colonial association regime. By incorporating a large part of Africa’s natural resources into a western European sphere of influence, the European Economic Community aspired to emerge as a “third force” in world geopolitics, able to balance the Soviet Union and the United States.

Peo Hansen – The colonial origins of European integration. (LSE Blog, 31/10/23)

As Slobodian and Hans Kundnani commented, the ‘Eurafrica’ project never went away, and remains at the core of what the EU is:

Looked at from another perspective, Eurafrica never died. France has more than 3,000 troops in Africa and has intervened in postcolonial Africa over three dozen times. Frontex, the EU’s border and coastguard agency, has plans to expand its footprint in African countries. Spanish enclaves and autonomous port cities still exist on the continent – Ceuta and Melilla – and an increasing number of African states are offering citizenship by investment even as many postcolonial elites stash their wealth in Mayfair property and Swiss bank accounts.

Quinn Slobodian – The delusion of a new European empire (The New Statesman, 17/06/23)

The European Union’s distinctive approach to migration depends on what might be called the offshoring of violence. Even as it has welcomed millions of Ukrainian refugees, the bloc has paid authoritarian regimes in North African countries to stop migrants from sub-Saharan Africa from reaching Europe, often brutally. Through this grotesque form of outsourcing, the union can continue to insist that it stands for human rights, which is central to its self-image. In this project, the center right and far right are in lock step. In July, Ms. Meloni joined the head of the European Commission, the bloc’s executive arm, and the Dutch prime minister to sign one such deal with Tunisia.

The blurring of boundaries between the center right and the far right is not always as easy to spot as it is in the United States. Partly that’s because the process, taking place in the complex world of the bloc, is subtle. But it is also because of a simplified view of the far right as nationalists, which makes it seem incompatible with a post-national project like the European Union. Yet today’s far right speaks not only on behalf of the nation but also on behalf of Europe. It has a civilizational vision of a white, Christian Europe that is menaced by outsiders, especially Muslims.

Such thinking is behind the hardening of migration policy. But it is also influencing Europe in a deeper way: The union has increasingly come to see itself as defending an imperiled European civilization, particularly in its foreign policy.

During the past decade, as the bloc has seen itself as surrounded by threats, not least from Russia, there have been endless debates about “strategic autonomy,” “European sovereignty” and a “geopolitical Europe.” But figures like President Emmanuel Macron of France have also begun to frame international politics as a clash of civilizations in which a strong, united Europe must defend itself.

In this respect, Mr. Macron is not so far from far-right figures like Mr. Wilders who talk in terms of a threatened European civilization.

Hans Kundnani – Europe May Be Headed for Something Unthinkable (NYT, 13/12/23)

A few years ago, Joey Ayoub similarly noted:

What the EU is guilty of doing here is, in effect, a normalisation of the far-right’s desire to inflict violence against the ‘other’. When tear-gassing children becomes normalised, it won’t be long before they’ll start being killed by people who will livestream it on Facebook. We are witnessing a dark chapter in European politics and if this is not immediately stopped it will get darker.

This hostility towards the ‘other’ is best symbolised, not by the far-right, but by what is considered the centre in European politics. In what can be described as the most honest statement by a member of the European Parliament, Guy Verhofstadt, the former leader of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe group,tweeted in April 2019 that “we need to better protect our external borders to keep our internal EU borders open”, implying that the arrival of undesirables is so threatening that it could undo decades of intra-European bridge-building.

Joey Ayoub (2020, April 2) Why Fortress Europe and the European Union can’t coexist. Byline Times. (Note: this title/framing is kinda questionable because as we’ve seen, the barbarism of “Fortress Europe”/Frontex is no deviation from the European project, but a logic consequence/outgrowth thereof)

As Anievas and Saull argue in the paper I quoted at the beginning, far right forces shouldn’t be seen as incompatible with liberal orders, but indeed as constitutive to them (yet ambivalent; it’s not a linear functionalist logic), because they offer “an alternative ideological legitimation of capitalist social orderings from that of liberalism”. Moreover, the differentiated state/police/border violence against oppressed (racialized, colonized, dehumanized, gendered) groups that characterizes all nation-states, no matter how liberal or leftist its government claims to be, is inherently a fertile ground for the development of the far right’s murderous fantasies/goals. Notoriously, milieus like the police and the military attract a lot of authoritarian, racist, and reactionary elements (not infrequently outright fascists).

The logical endpoint of this project of unifying “Europe” as a neo-imperial association of nation-states with militarized borders and policing to protect “European civilization” against the putative “Other” or “invader”, is the kind of murderous barbarism that the continent saw during the darkest hours of the past century, from widespread forced sterilizations to Kisielin, to Jasenovac, to Srebrenica, to Chełmno… In a rare moment of lucidity from West European intellectuals/commentators during the Bosnian genocide, Baudrillard hit the nail on the head:

In fact, neither the grotesque gesticulations of the international powers nor the sickened outcries of the stewards of good causes can have any real effect, since the decisive step has not been taken. No one dares nor wants to step up to the final analysis, to recognize that the Serbs are not only the aggressors (…), but are our objective allies in the cleansing operation for future Europe, freed of its bothersome minorities, and for a future world order, freed from all radical challenges to its own values – based on the democratic dictatorship of human rights and on free markets.

What is at stake is the question of evil. By denouncing the Serbs as “dangerous psychopaths” we pride ourselves for having put our finger on this evil, without questioning the innocence of our democratic intentions. We suggest our job is done once we have declared the Serbs the “bad guys,” but not the enemy. With good reason, since from a world perspective, we Westerners, we Europeans, are fighting exactly the same enemies as the Serbs are: Islam, the Muslims. Everywhere, in Chechnya with the Russians (the same shameful, deadly intolerance); in Algeria, where we denounce the military powers, all the while giving them major logistical support. (…) The short of it is that we will bomb a few Serb positions with smoke-mortars, but we will never really intervene against them, since their work is basically our own. If it were necessary to end the conflict, we would rather break the backs of the victims, since they are far more irritating than the executioners.

Jean Baudrillard: The West’s Serbianization (Libération, July 3, 1995, Translated by James Petterson). Published in This Time We Knew: Western Responses to Genocide in Bosnia, edited by Thomas Cushman and Stjepan G. Meštrović, p. 85. NYU Press, 1996.

Today the situation concerning Palestine is even more grim: while there’s also an ongoing genocide, this time Western powers and governments have fully supported and endorsed Israel’s actions, dropping any pretension or attempt to oppose the massacres (and indeed more often than not, denying that it actually is a genocide, which couldn’t be more obvious).

Literature

Hans Kundnani (2023) Eurowhiteness: culture, empire and race in the European project. Hurst: London.

Peo Hansen & Stefán Jónsson (2014) Another Colonialism: Africa in the History of European Integration. Journal of Historical Sociology, 27:3, 442–461.

Peo Hansen & Stefán Jónsson (2017). Eurafrica Incognita: The Colonial Origins of the European Union. History of the Present, 7:1, 1–.

Peo Hansen & Stefán Jónsson (2014) Eurafrica: The Untold History of European Integration and Colonialism. Bloomsbury Academic.

Alan Milward (2000, 2nd Ed.[1992]) The European Rescue of the Nation-State. Routledge: London and New York.

Joshua Clover (2020) Empire of Graveyards. Crisis & Critique, 6:1, 88-103.

Harsha Walia (2021) Border and Rule. Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism. Haymarket Books.

Nicholas De Genova (2016). The “Crisis” of the European Border Regime: Towards a Marxist Theory of Borders. International Socialism, (150), 31-54. [PDF version here]

Nandita Sharma (2020) Home Rule: National Sovereignty and the Separation of Natives and Migrants, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Nandita Sharma (2021) Against National Sovereignty: The Postcolonial New World Order and the Containment of Decolonization. Studies in Social Justice. 14(2): 391-409.

Alain Bihr (2000) Le crépuscule des États-nations. Transnationalisation et crispations nationalistes, Lausanne, Éditions Page deux.

Benjamin Thorpe (2018) Eurafrica: A Pan-European Vehicle for Central European Colonialism (1923–1939). European Review, 26:3, 503–513.

Mark Bassin (2023) “Everything Is Revealed in Maps”: The European Far Right and the Legacy of Classical Geopolitics during the Cold War. Geopolitics, 28:5, 1843-1867.