Conspiracy theorists erase the human aspect of history. My child — who lived, who was a real person — is basically going to be erased.

Lenny Pozner, father of one of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting victims.

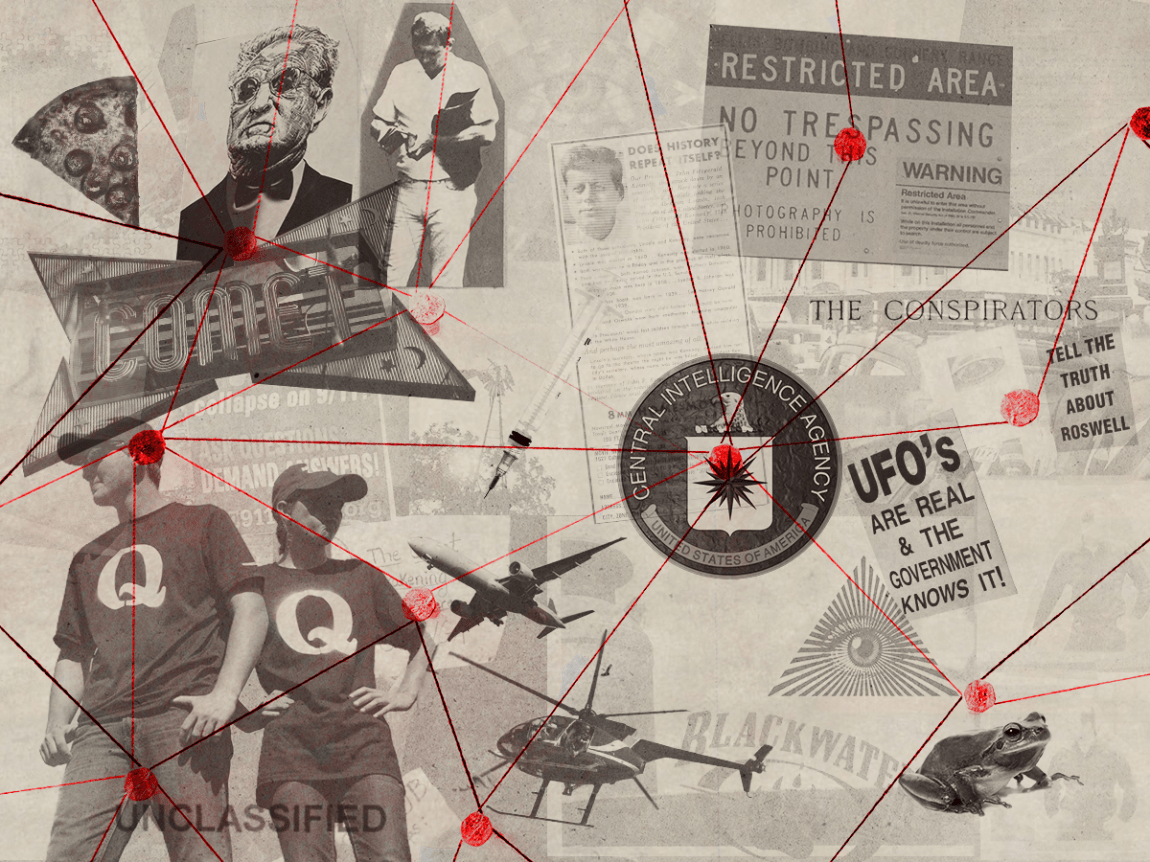

As interesting as exploring the crazy and sometimes quirky world of the things and batshit alternative histories some people believe in can be, the framing of conspiracism as a silly and funny curiosity, as this ridiculous escape world for ‘tinfoil hat’-wearing ‘crackpots’ who believe in stuff like the reptilians, flat Earth, or the Secret Space Program, is ultimately harmful. There’s no denying that there can be something really intriguing and entertaining about some of those ideas and stories, but Lenny Pozner’s heartbreaking testimony stands as a *record scratch* reminding us of the dark reality that underlies this issue/discussion.

Before he turned into a 24/7 pro-Trump mouthpiece and before his horrendous behavior around the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre, Alex Jones used to be perceived (wrongly) – much like David Icke in the UK – as this kind of “silly” and “funny” conspiracist figure. Lenny Pozner said “I probably listened to an Alex Jones podcast after I dropped the kids off at school that morning”, wich is so devastating since it was Jones, his staff and his audience who played the major part in harassing the Pozner family and prevent them from being able to have an untroubled grieving process. The hosts of the Knowledge Fight podcast, who have been examining Jones’ show for many years, have repeatedly showed and emphasized that presenting him as a comedic figure is problematic and very dangerous. Indeed when you start looking into the milieux and actors that have insane conspiracist worldviews and beliefs, you will sooner or later realise that there are always reactionary, cultic or otherwise dangerous elements…

There could be an endless discussion about the psychology and sociology of beliefs, ideology, rumors/urban legends, myths and collective/individual paranoia or moral panics, but narrowing down the question of conspiracism is helpful: it functions as a substitute for social critique, i.e. for an actual radical perspective that breaks down the structural and systemic forces underpinning most economic and social problems. According to Marx, “To be radical is to go to the root of the matter. For man, however, the root is man himself.” But as @thecoleslaws once said: “Conspiracism is the brain rot that destroys all materialist thinking.” And it is therefore a major obstacle to radical emancipation and social revolution.

But as the analysis and critique of denialism – conspiracism’s close cousin – shows, we cannot approach this issue as merely a question of self-deception, flawed theory or lying. The conservative and elitist tendency to pathologize these individual and collective behaviors in terms of psychological instability (e.g. Hofstadter’s ‘paranoid style’ of politics) or cognitive/intellectual deficiency (or irrationality), is both conceptually/analytically counter-productive and politically reactionary. Instead, a critical socio-political perspective which recenters the social processes and political configurations that underlie conspiracism, is necessary.

Conspiracism

The Structural and Sociological Foundations of Conspiracist Thinking

Humans just lead short, boring, insignificant lives, so they make up stories to feel like they’re a part of something bigger. They want to blame all the world’s problems on some single enemy they can fight, instead of a complex network of interrelated forces beyond anyone’s control.

Pearl, Steven Universe, “Keep Beach City Weird”. Cited here.

First, it is necessary to make a distinction between conspiracies, conspiracy theories, and conspiracism. Actual conspiracies or “plots” do exist, needless to say. A well-known example is the long history of the U.S. attempting to change or overthrow other governments (as many as 72 times during the Cold War, for example in Africa or the Iran-Contra affair). A conspiracy theory is a ‘specific theory aiming to explain a social, political, economic or geopolitical phenomenon in terms of a plot’. On the other hand, conspiracism is a ‘totalising theory explaining history as the product of a single conspiracy broken down into a multitude of plots’.

This distinction is important because, as Sortir du capitalisme argue, secret actions, plots and strategies are a real part of ordinary social domination as opposed to any “Machiavellian anomaly”:

[A] materialist analysis [recognises] that there are indeed secret actions by dominant social actors within capitalist firms and states, that they seek to increase their profits and their power (…) However, this does not mean that they are conspirators, since they do not act primarily within secret societies/groups, but simply within governments, protected by ‘state secrecy’, and within companies, protected by ‘business secrecy’, and are therefore part of the ordinary/normal relations of domination rather than a Machiavellian anomaly.

According to some historians, modern conspiracism emerged during the French and American revolutions [Reza Zia-Ebrahimi, Antisémitisme & islamophobie. Une histoire commune, p. 89], when some people in both countries pointed the finger at some ‘shadowy’ groups – largely liberal/anti-monarchy or contrarian secret societies – like the Illuminati or the Free Masons, to try to make sense of these unprecedented events that most people at the time struggled to understand/grasp. Undoubtedly, the historical origins of conspiracist thinking – if there even is such a definite starting point – could be extended back to older religious/theological and racist paranoia, such as the longstanding antisemitic tropes that certainly existed before the 18th century. But in general as well as here specifically, I’m mostly interested in and focusing on modern social forms and phenonema. Using an example from France, critical theorist Benoît Bohy-Bunel provides a useful interpretation:

The context in which [this] specifically modern conspiracy theory arose reveals its essence and raison d’être. In 1798, the abbot Augustin Barruel denounced an “anti-Christian plot” at work in the French revolutionary movement. This is how the first form of conspiracy theory in the modern sense emerges, while precisely the dynamic by which the “conspiracy” in the traditional sense was becoming increasingly impossible is initiated. In fact, the formal universalism that was triumphing in the political field, is based on a new juridical structuring of socio-economic conditions rooted on the abstraction of value, the impersonality of the market and axiological neutrality, as opposed to the concrete and theologically oriented personalization of feudal relations. While politics was ratifying an unprecedented opacity in class relations, where the rulers are themselves ruled by empty abstractions over much they have no real hold, and where they have no “real” control over the society they are supposed to govern, paradoxically the first attempts at decyphering modern social relations by singling out an hyperconscious but concealed omnipotence of a very precise minority, arose.

This apparent contradiction sheds light on the intrinsic function of conspiracism, which is a properly modern way of looking at the human world: it tends to reinject subjectivity, responsibility, personality, and agency, where they are increasingly lacking.

Benoît Bohy-Bunel (2016) Le conspirationnisme antisémite, patriarcal, homophobe.

[note: historians like Emmanuel Kreis actually consider Augustin de Barruel’s 1797 book Mémoire pour servir à l’histoire du jacobinisme as the founding/first work of modern conspiracism]

As Chip Berlet and Matthew N. Lyons said:

Conspiracism blames individualized and subjective forces for economic and social problems rather than analyzing conflict in terms of systems and structures of power. Conspiracist allegations, therefore, interfere with a serious progressive analysis–an analysis that challenges the objective institutionalized systems of oppression and power, and seeks a radical transformation of the status quo.

Chip Berlet & Matthew N. Lyons (2000) Dynamics of Bigotry. Political Research Associates.

Aaragorn Eloff therefore writes that “the danger of conspiracy theories is their ability to breed apathy and resignation, offering an easy narrative that makes people susceptible to influence and limits social change”:

Distinct from the kinds of concrete political analyses that are able to explain these unequal power relations in terms of complex dynamics involving myriad social, political, economic and historical forces, however, conspiracy theories operate with a highly simplified understanding of these aspects of social reality, turning social forces into individual Bond villains and systemic conditions into cabals of all-powerful evildoers. This simplified narrative structure, which tellingly reflects dominant modes of subjectivity and the cult of the personality that has arisen under neoliberalism, also partly explains the appeal of conspiracy theories for large numbers of people looking for a stable foothold in an increasingly complex world.

Bohy-Bunel extends his argument by using Marx’s critical theorization of capitalist social relations:

In his analysis of capitalist society, Marx insists on the specificity of capitalist social relations, as opposed to social relations in feudal and slavery-based systems. (…) Within modern relations of production, in the same way that “the worker is only the personification of labor”, “the capitalist is only the personification of capital”. In other words, economic agents, whether “exploiters” or “exploited”, are ultimately driven – albeit differently – by abstract categories whose logic generally escapes them. (…) Value (…) is the means and the end of capitalist society: it is that by which commodities become commensurable with each other, and that which is to be accumulated indefinitely; not concrete humanity in the flesh, but human labor congealed into its products as a pure abstract quantity, (…) “abstract labor”. Its existence as an autonomous entity lies in (…) the capitalist process of setting up money, the medium of exchange, as an end in itself, in that it would possess the quasi-magical quality of increasing in the process of exchange (in reality, it is the existence of surplus value, extorted from the wage-earner, that makes this increase possible). In [this structural setting], it goes without saying that the individual, with his agency, his desires, and his conscience, does not really have “a say”, even in the case where he owns the means of production. He is essentially a force without will guided by the impersonal logic of commodities. Here, therefore, no psychologization, no moralization of the relations of domination is appropriate, at least not in the immediate sense. Certainly, it is always possible to identify a group of the privileged and a group of the downtrodden within the social structure, the managers and the exploited, insofar as the division of labor and the distribution of produced goods/wealth remain hierarchical/unequal. This in turn leads to some necessary struggles. But it is not relevant to assume immediately explicit intentions on the part of the powerful, because no “moral” project, no responsibility, no conscious desire seems to assert itself through their own cold-blooded calculations: they seem themselves, pitifully, to be only the toys of a matrix they do not control.

Thus, conspiracism appears at the same time as power tends to become ever more impersonal, asocial, amoral, non-human.

Benoît Bohy-Bunel (2016) Le conspirationnisme antisémite, patriarcal, homophobe.

Bohy-Bunel is right not to merely dismiss the real actuality of economic hierarchy and concrete social struggles, because authors within the strain of thought he’s coming from – the so-called Wertkritik – tend to erase the sociological materiality of relations of domination and, as Gerhard Hanloser commented in 2005, “[lay] a protective hand over the “character masks” of capitalism and its institutions – although this favor hasn’t even been requested”. Without going too much off topic, let’s just remember that the impersonal/abstract dimension doesn’t erase the sociological concreteness of capitalist social relations:

the external relations between the units of production, from which the theory of value proceeds, presuppose a certain internal organisation of these units, namely the production of surplus value on the basis of wage labour. The seperation between the units of production presupposes the separation between the immediate producers and the means of production, or, the horizontal relations presuppose the vertical relations (…) Or, yet again, boiled down to the essentials: value presupposes class. Class domination is inscribed in the commodity form from the very first page of Capital.

Søren Mau: Mute Compulsion. A Theory of the Economic Power of Capital, p. 177.

To sum up, the real sociological dynamics of class hierarchy and struggles and the structural and impersonal/abstract logic of the capitalist system, coexist. So the social ‘roles’ played by capitalists and powerful social groups/actors shouldn’t be downplayed: there are still agents of domination, not merely ‘masks’ that could be transferred to anyone (e.g. poor proletarians don’t become rich entrepreneurs for a reason) But that doesn’t imply that a moralization of this social dynamic – for example in populist terms, the hard-working ‘people’ versus the corrupt, greedy ‘elite’ – is appropriate. As Sortir du capitalisme addressed in the passage I quoted above, “they are part of the ordinary/normal relations of domination rather than a Machiavellian anomaly”. Shane Burley emphasizes this populist (and class collaborationist, or “interclassiste” in French) dimension of conspiracism:

Conspiracy theory manifests a classic perversion of this general understanding away from a role in the system toward scapegoating specific people. It creates an inherently “class collaborationist” model in which a type of person, partially in and partially out of the ruling class, behaves as a foreign enemy, thereby calling members of all classes to unite in opposition to their pernicious influence. More than this, their motivations are more covert, money and power are not good enough reasons for the conspiracy theorists. Instead, a particular population of people (Who could it be?) use crypsis to hide themselves and inhabit even more profound spheres of influence.

Shane Burley (2019) The Socialism of Fools. Journal of Social Justice, Vol. 9, p. 13.

Stoff likewise tie today’s conspiracism to capitalist social relations:

Conspiracism is being revived by a nebulous number of groups and small groups that are proposing a reading of the current crisis, distributing the roles of victims and culprits. It’s a system of certainties whose fixity is reassuring. Admittedly, the times are good for it: the immense accumulation of commodities forms the spectacle of a world where reason has been lost, where production is no more than a means to the permanent expansion of surplus value. This process of accumulation obeys a structural logic, identified long ago with the normal course of evolution, and this is why it escapes easy and immediate comprehension. It is here, precisely in this difficulty, that the strength of conspiracism lies, much more so than in the deficiencies of the information produced in the context of the monopolistic concentration of the mass media. Ignoring the historicity of capitalism, the conspiracist sees in everything only will and strategy, manipulators and useful idiots, which has the effect of avoiding any questioning of the economy and its categories. There is a subjectivity at work, hiding behind the seemingly disorderly movements of the markets. A subjectivity that, once identified, can and must be fought. This is what draws conspiracy theorists into the orbit of populism: the unveiling of domination within Western societies, by means of the “conspiracy”.

Translated from Stoff: Populisme. Une trajectoire politique de l’humanité superflue.

Finally, Julien Giry’s comprehensive breakdown of conspiracism in the U.S. contains some key notions for defining and understanding the sociological underpinnings of this phenomenon. As we already saw in Bohy-Bunel’s argument, it constitutes “a conspiracist re-enchanting of the world” (or “postmodern mythology”) that responds to the “sociological phenomenon of political alienation”, that is, the fact that “a certain number of social actors are distancing themselves from the political, institutional and moral system, either intentionally (political radicalization) or not (uncertainty, incomprehension, “symbolic violence“).” As Giry explains further:

the exponential development of the conspiratorial frame of reference must be interpreted as a response of defiance to the traditional socio-political and moral frames of reference for interpreting a complex, multipolar and globalized world; it then becomes a populist mode of explanation of the world and its events, which is simplistic and Manichean, audible and understandable by each and every one.

Julien Giry (2014) Le conspirationnisme dans la culture politique et populaire aux États-Unis. Une approche sociopolitique des théories du complot, p. 9.

In addition to alienation, what must therefore be analyzed is the process of politicisation, as emphasized by Emmanuel Taïeb:

Political modernity, the birthplace of conspiracism

It is in this perspective that conspiracy can be understood as the fruit of political modernity. Indeed, since Claude Lefort, we know that the French Revolution, political contractualism and the autonomy of societies have turned power into an ’empty place’ (Lefort, 1994). However, the political indeterminacy constitutive of the democratic principle has conditioned, writes Marcel Gauchet, a ‘phantasmatic ambition of reincorporation, of restoration of the social one as a body’ (Gauchet, 1997: 450), in order to fill up this empty place again. Either via a reactionary discourse aiming to reincarnate power in the royal body, or via totalitarianism, which sought to fill the empty place of power with the body of the masses or that of the leader. Conspiracism then appears as an attempt to designate the real power behind the empty place of democratic power. [p. 277]

A ‘conspiratorial politicisation’

It therefore seems essential to us to analytically ‘repoliticise’ conspiratorial discourse as an act of language carried by particular actors pursuing political objectives. Rather than thinking of conspiracy as a traditional marvel, rather than psychiatrising it or understanding it as a survival of the irrational in modernity, it is more appropriate to study the use that is made of it to politicise a certain number of issues. And by ‘politicising’ we mean publicly re-characterising [/re-framing] factual information about certain events as issues whose meaning is contested and calling public and political actors to account for it/react to it. We can see that conspiratorial discourse is used as a resource and as a political stunt by politicisation entrepreneurs. Using conspiratorial rhetoric is an effective way for them to participate in the legitimate/conventional/hegemonic political process. For conspiratorial discourse has a performative aim: by disseminating the conspiracy thesis, it intends to make it triumph in people’s minds, to influence the political agenda, to impose the alternative knowledge on which it is based, and to make political reality conform to this worldview. [p. 280]

Emmanuel Taïeb (2010) “Logiques politiques du conspirationnisme“. Sociologie et sociétés, 42, no. 2, p. 277; 280.

Now that its sociological and structural determinations have been outlined, let’s take a look at the concrete functioning/logic of modern conspiracism.

How Conspiracism Works

According to Julien Giry, conspiracism concretely emerges through the combination of a structural-cultural dimension, the emergence of/roles played by conspiracist “leaders” and some specific scapegoat(s), and some kind of extraordinary – literally, out of the ordinary – event that “that will give rise to, and serve as the starting point and impetus for conspiracy interpretations and conspiracy theories” (Giry 2014: 25):

The combination of these three elements (…) gives conspiracy theory life in the public arena and in public opinion to the extent that, like rumour, it achieves real visibility and even a certain legitimacy, since it finds relays within the legitimized/hegemonic political, intellectual and media spheres. So conspiracism is not, as often presumed [by bourgeois ideologues], relegated to the margins, to the extreme right of the (…) political field or to the working classes with little cultural [sophistication/education]. On the contrary (…) it radiates widely across the whole political and social spectrum (…) Moreover, it’s important to discard once and for all the moralising and cynical [bourgeois] prejudice according to which conspiracism is the sole preserve of the working classes, presumed to be vulgar, intemperate, unpredictable/inconsistent, unruly and authoritarian, prone to passions and irrational. On the contrary, conspiracism is a social phenomenon that [also] affects academics, engineers, politicians and leading journalists. [Giry 2014: 27]

He defines the structural-cultural dimension in socio-cultural terms:

the force of habit or repetition in the political and social history of a State of the formulation of conspiracy theories, the profusion of conspiracy secret societies or political sects, a conspiracy socialisation through popular culture (internet, cinema, television, music or adolescent literature), that is to say “a cultural system of large real groupings occupying a subaltern and dominated position in global society “[Lavile d’Epinay et al. 1982] giving credence to or widely supporting, among the general public, conspiracy theories. In other words, it is the constitution of a conspiratorial culture which, for example, in the case of the United States, can take the form, since Independence, of a general suspicion or suspicious a priori towards the federal government largely maintained by contemporary Hollywood cinema and certain television channels, Fox News in particular. [Giry 2014: 26]

I would simply add to this structural dimension the sociological determinations relative to bourgeois modernity that were outlined above. In summary, as Sam Moore and Alex Roberts write in their brilliant book Post-Internet Far Right:

The psychological explanation for conspiracies is obvious: the world, which is an intimidating and increasingly confusing place to be in, can be made simple. All its complexities – and the intense sense of ignorance that one must face when trying to say anything – can be reduced into a single narrative. Better yet, this narrative is flattering to an individual’s prior beliefs about themselves, others, or the groups to which they belong. Conspiracy theories’ explanatory simplicity, which cuts cleanly through thick jungles of information, comes at the price of any tests for truth. Because explanations go untested, they feel deeply true, even certain, as they fit flush to your most basic prior beliefs. This can feel like ‘thinking for yourself’ – maintaining a certain intellectual hygiene – which is rare and pleasant in our informational deluge. As society demands more and more cognitive power to navigate, explanatory ability becomes a defining marker of a person’s worth, and turns explanation into a saleable commodity hawked by far-right influencers.

Why, despite this apparent freedom to think anything, do the contents of conspiracy theories follow such predictable patterns? It’s not mere individual psychology that explains the often-predictable themes of conspiracies – their texture and uptake is afforded by the organisation of society. Our prior beliefs are not simply stuck in our heads, rather, they circulate, are played out in practice, and are selected at a wider social level.

There is no exhaustive list of where this selection might happen. After neoliberalism shredded the sites of democratic contestation, conspiracy theories provided a site for antagonism to be expressed. The traditional sense-making institutions of society are present here mostly negatively, as everything that conspiracists resist, although arguably news organisations in the Anglophone world have taken a turn for the conspiratorial too – perhaps most prominently The Sun’s publishing of neo-Nazi conspiracy theory materials in 2019. Instead, we must look to an ever-expanding list of dark and private places to see where this bubbling of conspiratorial thinking is going on: in conversations and their disappointments, in political organising and its failures, in individual hunts for information online, in the slow drifting apart of already atomised individuals, in a rapidly swelling and ramifying sense of personal betrayal. Broad social and technical changes have shifted the landscapes in which conspiracy communities form. They are obviously not exclusively modern phenomena – antisemitic conspiracies, for example, have been operative for far longer. But their density has increased in the modern period, and accelerated further since the rise of the internet.

Why? Sociologist Luc Boltanski argues that, in modernity, national boundaries of predictable reality have been overrun by capitalism’s international drive. As capitalism overflows these stable sense-making boundaries, ‘the reality of reality’ becomes suspicious – things start to seem uncertain at a profound level. Because there exist now, either on the far right or in society at large, almost no structured programme of political education, ideas can rarely be overturned wholesale – they must be changed piece by piece. It is this transformation that memes afford, in part. They shift from very amorphous perceptions of isolated phenomena to very high-level and general explanations. In modernity, everything can seem to be coming from the outside: zoonotic viruses, hijacked airplanes, government intervention into life, alien masters of the universe.

Following Giry (2014: 30-31) and Keeley (1999: 116-118), we can describe conspiracy theories based on a couple of common characteristics. All conspiracist theses/theories reject some “official”, received accounts/explanations by (legal-rational) authorities, mainstream media and institutions of socialization (family, school, church, etc.). Instead they claim/believe that conspirators are an invariably nefarious and corrupt shadowy force with singularly evil intentions, which connects together a number of seemingly unrelated events, tragedies or cataclysms. The ‘truth’ about these tragic events is systematically concealed from the general public, and known only to a few insiders. But conspiracist leaders identify/discover what Keeley called errant data, i.e. disturbing/troubling facts that lend credence to conspiracist beliefs; simultaneously, they systematically discard anything that doesn’t fit into their narrative scheme/worldview.

These errant data usually take two forms (either or both): “unaccounted-for data” – stuff left out of authorities’ official version/narrative/account – or “contradictory data” – tiny bits of data/info or details (real or imagined/made up) that are seen as incompatible/incongruent with the official narrative, throwing a small part of it into question, which for conspiracists implies that the mainstream account/official version can be dismissed as a whole. In conspiracists’ cryptological and esoteric mode of thinking, less evidence is the ultimate proof of the existence of a conspiracy: the fewer real (and especially official/mainstream) clues of a conspiracy there are, the more obvious its existence is because it reveals its concealment from the public.

What distinguishes conspiracist theses from warranted accounts/discussions of conspiracies – say, in cases like the Iran-Contra Affair and Watergate – is, according to Keeley (1999: 123), the “increasing amount of skepticism required to maintain faith in a conspiracy theory as time passes and the conspiracy is not uncoverred in a convincing fashion”. Conspiracists rely on spurious correlations/claims, on negating/denying the complexity and dialectical logic/dynamic of modern phenomena/social systems, and on an idealist/fetishistic conception of history and social domination which them a mythical structure rather than a materialist one. In other words, Manichean and truncated understandings of social relations and modern politics replace the emancipatory critique of bourgeois modernity which recognizes that inhuman violence and domination – including secretive actions, deals or plots, occasionally – is not something extraordinary or abnormal, but the normal part of captialist society.

Reactionary Critiques of Capitalist Modernity, Antisemitism & Confusionism

Conspiracism represents a failed and flawed attempt at a critique of the prevailing sociopolitical order. Various terms have been used to refer to this, but following Mia Wong, we can simply call it incomplete or partial critique: various forms of incoherent populism that condemn or attack certain (real or imagined) features of the system but “ultimately fail to fully grasp the nature of capitalism” [note: Mia rightly adds “settler colonialism” here, concerning the American context]. Just to clarify that this isn’t a crude “class-first” (or even “capital-first”) reductionist argument, this is about capitalist society as a whole – capitalism as the modern social totality -, not merely the “economic” dimension: clearly, certain forms of conspiracism are rooted in failing to understand, for example, the gender or racial (or “racist”) dimensions of modern social relations.

Through this failed and often reactionary, nostalgic, romantic critique, the contentious or even rebellious energy that can emerge from capitalist alienation is either neutralized or directed into dangerous and non-revolutionary paths. This is one of the main underpinnings of “populism” since the 19th century: tapping into widespread feelings of injustice, economic anxiety/insecurity, class anger and so on, by producing a (usually) confused and class-collaborationist framing of the social antagonisms, often using chauvinist, racist, and xenophobic sentiments. The abstractness and illusory forms of appearance of value and capital – and the various forms of fetishism that go with them – can therefore produce pseudo-emancipatory understandings and politicizations, that give individuals and movements a feeling of “standing up against the system/the elites/the powers that be” whereas they usually aren’t and merely target scapegoats (e.g. immigrants) or certain parts of capitalist social relations (e.g. merely denouncing and opposing “financialization”, banks and so on).

One of the classic contributions on this topic is Moishe Postone’s “Anti-semitism and National Socialism”. And here’s is Iyko Day summarizing the main argument of her work adressing “romantic anticapitalism”:

In the nineteenth century, we can see how the social consequences of this antinomical view of capitalist social relations emerge and take on racial significance. As capitalism underwent rapid expansion, the externalization of abstract and concrete forms intrinsic to the fetish of commodities became increasingly biologized and racialized in concert with prevailing socioscientific conceptions of the world. The proliferation of scientific racism with the rise of social Darwinism in the late nineteenth century demonstrates how society and historical development were increasingly understood in biological terms, moving from a more mechanical or typological worldview, in which events were a reflection of divine power and design, to a more secularized, biologized worldview that naturalized an antinomical view of capitalist relations. Related to this is a regressive-romantic attachment to a revitalizing and pure construction of an unchanging nature, in contrast to the alienation attributed to capitalist modernity. Expressing the antinomy of concrete and abstract, nature therefore personifies concrete, perfected human relations against the social degeneration caused by the abstract circuits of capitalism.

(…) In my book Alien Capital, I argue that a settler colonial ideology of romantic anticapitalism constructs Asians as the racialized embodiment of the destructive abstractions of capitalism by projecting a kind of perverse, excessive efficiency onto their bodies. Figured alternatively as cheap labor or as efficient model minorities, Asian racialization has consistently turned on notions of excessive economism. The economism of Asian racialization is rooted in the nineteenth-century temporal alignment of fungible Chinese bodies with abstract labor. White settler ideology hypostatized the concrete, pure, and organic dimensions of white labor and leisure time, while identifying capitalism solely with the abstract dimensions of the antinomy, personified by Chinese labor. In the context of railroad building, the temporal excess associated with Chinese bodies through their higher rate of exploitation was combined with the perversity connected to the nonreproductive spheres of Chinese homosocial domesticity. This rendered Chinese labor a quantitative, temporal threat to the qualitative and normative temporality of white social reproduction. The temporally excessive and fungible character of Chinese labor was the foundation on which Asians have been associated with a destructive value regime.

Similarly, before the expulsion and relocation of 120,000 Japanese Americans from the west coast into internment camps during the Second World War, we can also observe the development of an increasingly unnatural, mechanical abstraction attributed to the Japanese. Building on Colleen Lye’s argument that Japanese Americans were associated with monopoly capital, I argue that the association of Japanese labor with the modernizing displacements of technological innovation fed the perception that Japanese labor monopolized the creation of relative surplus value. Here, Japanese labor is associated with a destructive value regime that threatened white agriculture and the fishing industry.

On the flip side of the economic abstraction tied to Asian racialization, romantic anticapitalism imagines Indigenous peoples as entirely outside of capitalism or time, inviting a white settler colonial identification with the Indigenous that Shari Huhndorf calls “going Native.” Today’s white supremacists, too, sometimes idealize Indigeneity. In an interview with New Stateman, a self-described ecofascist claimed that “the import of these non-Europeans have brought in people who do not share the same respect for nature and especially not animals. Nor do they have the connection to the soil the natives have.” In the massacres committed in Christchurch, New Zealand, and El Paso, Texas, in 2019, the gunmen similarly justified the killing of immigrants as “protecting nature.” In the frame of romantic anticapitalism, non-European immigrants represent an abstract yet existential threat that is counterpoised with the concrete purity of Indigenous peoples and their connection to land. Of course, so-called white people are not indigenous to North America either. This is one reason white settler cultural identity is so heavily invested in appropriating Indigeneity. From Dances with Wolves to Avatar, white men are not only allied with Indigenous struggles against frontier violence and resource extraction but are revealed as “true” Natives, “ironically demonstrat[ing] white superiority even as [they] go native.” This mode of going native functions to erase the history of colonial invasion and genocide by reimagining a natural affiliation to land.

It is important to recognize the racist scope of this form of romantic anticapitalism. As an illustrative example, Huhndorf offers the surprising account of the publication of The Education of Little Tree, the autobiography of a Cherokee man that garnered praise for its sensitive and “true depiction of Cherokee beliefs and ways of life.” It was eventually discovered that the identity of the author, who went by the pseudonym Forrest Carter, was none other than Asa (Ace) Earl Carter, described as a “Klu Klux Klan terrorist, right-wing radio announcer, home-grown American fascist and anti-Semite” who was the speechwriter for Governor George Wallace’s racist 1965 speech opposing desegregation. Huhndorf reveals how nativist white supremacy can literally take the racial form of the “Native.” As she explains, “going Native” ultimately “serves to regenerate white society and naturalize its power.” Through the irrationality of romantic anticapitalism, the double character of the commodity is thus externalized as an antinomy of concrete and abstract dimensions, racially manifesting as an opposition between an abstract-value dimension associated with Asians and a qualitatively concrete dimension of Indigeneity. Settler whiteness, which has no biological substance beyond the political right to exclusive possession, actively strives to form a concrete body by eliminating and replacing the Indigenous.

Iyko Day (2020) The Yellow Plague and Romantic Anticapitalism. Monthly Review, 72: 3.

To sum up, as various people including Jacob Bard-Rosenberg and Ross Laurence Wolfe have warned, it is absolutely crucial for anyone who cares about abolishing and transcending capitalism in a progressive and emancipatory way, to systematically gauge the actual fundamental content of supposed critiques of and alternatives to the international bourgeois status quo…

More broadly part of the problem is that a section of the left seems to think that all opposition to the current state of things, or to capitalism, is equally radical: this thought puts critical theories of society and conspiracy theories of society on equal footing. It is up to the left to recognise that the most racist Jewish conspiracy theories were also nominally anti-capitalist (even if they tended towards a critique of circulation rather than of capitalist production, or suggested that profit was founded on a swindle as opposed to on brutal exploitation, or if they theorised an enlarged image of the state to set themselves up against instead of the real enormity of private property, or if they saw the problem as a malignancy of who runs the world as opposed to the malignancy of how it is run.) For this reason we cannot gather all “anti-Capitalists” under our banner, but have to reject those whose theories tend to end in racism and conspiracy theory; we need to criticise ourselves to root out these tendencies in our own thinking.

Jacob Bard-Rosenberg (2016) A Note on Left-Wing Antisemitism from an Anti-Zionist Jew.

Leftists often have this delusion where they think anyone who doesn’t simply parrot cable news anchors or political pundits is just an inch away from a comprehensive Systemkritik. Seeing the Illuminati behind everything is supposedly the first step on some inevitable road to a critique of the capitalist totality. Hence the isomorphy between the average “critical” narrative (including most leftist ones) and the antisemitic narrative. Both boil down to a critique of who makes up the management of a social structure — or at best, a critique of the mode of management — rather than a critique of the fundamental social relations themselves. It’s easier to stick with the idea that you just have to weed out “a few bad apples” than it is to tear apart the ideological fabric of everything that surrounds you.

Ross Laurence Wolfe (2016, May 2) “Structural antisemitism“, in Reflections on Left antisemitism. The Charnel-House [Blog].

While not being its only form, antisemitism has long been and still often remains a favored framing for this kind of conspiracist (non-)critique. Like all incomplete critiques, it is widespread in the phenomenon of red-brownism, because as Yannis Youlountas wrote:

[By] blurring analysis and political references, conspiracism is the main vector of the confusionist method, which proceeds by deliberately mixing reactionary and anti-authoritarian ideas and authors, national revolution and social revolution, the far right and the far left, or fascism and anarchism.

Denialism

Denial and denialism, such as climate/anti-vax/science or atrocity/genocide denial, are closely linked to conspiracism, and in many ways indistinguishable from it. However, it is arguably useful to keep both notions as two facets of political modernity: two sides of the same coin, of modern ideology in the sense of fetishism or camera obscura, in Marx’s terms:

For Marx, ideology is a form of practice, experience, discourse, and consciousness that distorts reality by presenting it in false ways

Christian Fuchs, Nationalism on the Internet. Critical Theory and Ideology in the Age of Social Media and Fake News, p. 21.

Keith Kahn-Harris, in his book Denial: The Unspeakable Truth, introduces denial/denialism as follows:

Denialism is an expansion, an intensification, of denial. At root, denial and denialism are simply a sub set of the many ways humans have developed to use language to deceive others and themselves. Denial can be as simple as refusing to accept that someone else is speaking truthfully. Denial can be as unfathomable as the multiple ways we avoid acknowledging our weaknesses and secret desires.

Denialism is more than just another manifestation of humdrum deceptions and self-deceptions. It represents the transformation of the everyday practice of denial into a new way of seeing the world and – most importantly to this book – a collective accomplishment. Denial is furtive and routine; denialism is combative and extraordinary. Denial hides from the truth; denialism builds a new and better truth.

In recent years, the term denialism has come to be applied to a strange field of ‘scholarship’. The scholars in this field engage in an audacious project: to hold back, against seemingly insurmountable odds, the find ings of an avalanche of research. They argue that the Holocaust (and other genocides) never happened, that anthropogenic (caused by humans) climate change is a myth, that AIDS either does not exist or is unrelated to HIV, that evolution is a scientific impossibility, and that all manner of other scientific and historical orthodoxies must be rejected.

(…)

While certainty can be dangerous, so is unbounded scepticism. Denialism offers a dystopian vision of a world unmoored, in which nothing can be taken for granted and no one can be trusted. If you believe you are being constantly lied to, paradoxically you may be in danger of accepting the untruths of others. Denialism blends corrosive doubt with corrosive credulity.

From this extract of chapter 1 (‘The Failure’) [PDF]. Also published in The Guardian (longer text).

And this blending of corrosive doubt with corrosive credulity is the central feature of denialism, despite the variety of its forms (broadly speaking, one of two types: historical/genocide/atrocity-denialism; science/health-medicine/climate change-denialism). In the words of Adnan Delalić:

It does not seek to establish facts but to destabilize them. It purports to seek the truth but aims to create the opposite: an ambience of uncertainty.

Adnan Delalić (2019, December 2) Wings of Denial. Mangal Media.

And in all instances or forms, this only and always serves and leads to reactionary forces and political projects. Which is why it’s crucial to fight it in all movements and radical circles. It’s inherently destructive and counter-revolutionary.

Further Readings/Resources/Links

- AR: Chomsky’s Long Career of Bullshit: A Guide/Resource.

- Sortir du Capitalisme [Podcast]:

- Aufheben (2016) The rise of conspiracy theories: Reification of defeat as the basis of explanation.

- Théorie Communiste (2020-21) Complotisme en général et pandémie en particulier.

- Antithesi (2021) The Reality of Denial and the Denial of Reality.

- La Horde (2014) En finir avec les théories du complot.

- Montreal Counter-Info (2020-21) Anarchy, Lockdown and Crypto-Eugenics: A critical response from some anarchists in Wales & England.

- Autre Futur – Le conspirationnisme: danger et impasse d’une critique sociale.

- Philippe Corcuff (2009) «Le complot» ou les mésaventures tragi-comiques de «la critique».

- Emma Klotz (2009) Dossier Conspirationnisme: le boulet de la critique sociale.

- Chip Berlet (2009) Toxic to Democracy: Conspiracy Theories, Demonization, & Scapegoating.

- Adnan Delalić (2019) Wings of Denial.

- Blake Smith (2018) Indonesians Hate the Chinese, Because They Are Jewish.

- Alain Bihr (1997) Les mésaventures du sectarisme révolutionnaire.

- Julien Giry (2014) Le conspirationnisme dans la culture politique et populaire aux États-Unis. Une approche sociopolitique des théories du complot. PDF: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01686574/file/Giry_Julien.pdf

- Julien Giry (2015) Le conspirationnisme. Archéologie et morphologie d’un mythe politique [English translation].

- Julien Giry (2017) A Specific Social Function of Rumors and Conspiracy Theories: Strengthening Community’s Ties in Trouble Times. A Multilevel Analysis.

- Rachel Kuo (2017) Review of Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism by Iyko Day.

- Iyko Day (2017) Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism.

- Robert Sayre & Michael Löwy (2020) Romantic Anti-capitalism and Nature: The Enchanted Garden.

- Patrick Eiden-Offe (2023) The Poverty of Class: Romantic Anti-Capitalism and the Invention of the Proletariat.

- John Molyneux (2021) Capitalism, Romanticism, and Nature.

- Benoît Bohy-Bunel (2017) Le conspirationnisme antisémite, patriarcal, homophobe.

- Siniša Malešević (2022) Imagined Communities and Imaginary Plots: Nationalisms, Conspiracies, and Pandemics in the Longue Durée.

- Katie Terezakis (2020) The Revival of Romantic Anti-Capitalism on the Right: A Synopsis Informed by Agnes Heller’s Philosophy.

- Radio Free Humanity:

- Holocaust Controversies (a website combatting/debunking Holocaust denialism, sometismes Stalinist denialism too): https://holocaustcontroversies.blogspot.com/.